API Versioning - A Deep Dive

#92: Understanding API Versioning Strategies (14 Minutes)

Get my system design playbook for FREE on newsletter signup:

This post outlines API versioning strategies.

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Building application programming interfaces (APIs) is easy.

But keeping them stable and predictable as the system evolves is difficult.

API consumers depend on API contracts, and even a tiny change can break many integrations. For example, renaming a field, changing a response format, or changing an endpoint could stop someone’s production system from working correctly.

Business requirements change, so it’s necessary to communicate the API adjustments clearly.

That’s where versioning comes in. It provides a structured approach for evolving APIs without leaving the API consumers behind.

I want to introduce Irina Dominte as a guest author.

She’s a software architect, Microsoft MVP, with a passion for distributed systems, .NET, and system design.

Check out her blog and social media:

You’ll find her speaking at developer conferences around the world and blogging online.

API Versioning sets guidelines for introducing changes, shows how extensive those changes are, and ensures consumers can transition to new versions at their own pace.

But here’s the catch: just adding a version number in the URL doesn’t automatically prevent all the problems.

I’ve seen many APIs across different domains that expose a /v1/ in their URLs.

They add new data, change property names, change their types, remove fields, and so on. But years later, they run the same version even though the API has changed a lot.

And many APIs end up with v1 in the URL forever because the same organization controls the consumer apps as well.

So why add a version at all?

When different teams at the same company are the API owners and API consumers, version upgrades are “just” code changes. Teams can synchronize deployments, push breaking changes, and update consumers with little risk of breaking changes.

However, when you expose the API publicly and don’t own the consumers, the scenario changes completely. It means you cannot simply break compatibility.

You’re then limited by:

Service Level Agreements (SLA)

Legal contracts

Third-party dependencies

…all of which force you to design carefully and communicate clearly.

It’s better to avoid spending nights answering support calls because someone’s app broke when you changed an API endpoint.

Onward.

Build Real-Time Communication Experiences with Stream (Sponsor)

With Stream’s SDKs for React, React Native, Flutter, iOS, Android, and more, you can add production-ready chat, voice/video calling, activity feeds, and AI moderation to your app—with just a few lines of code. Backed by a global edge network and a generous free Maker plan, start prototyping today and scale to millions.

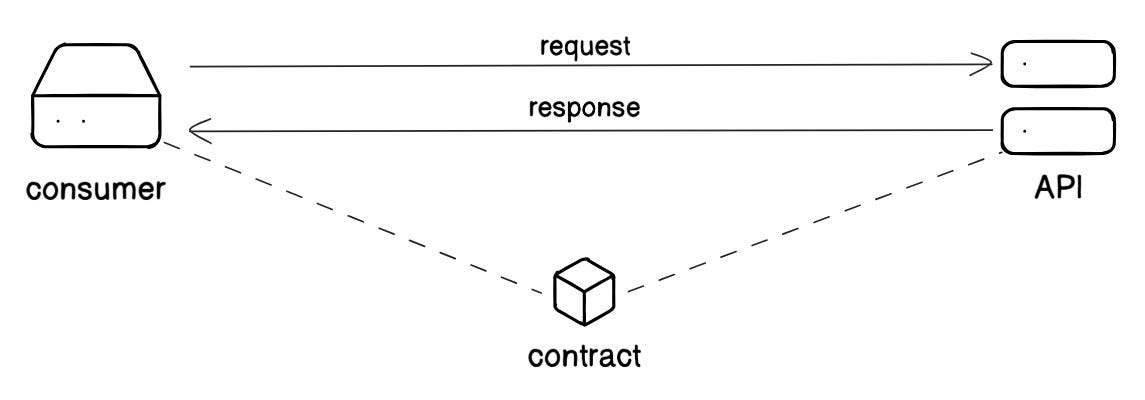

API as a Contract

It’s helpful to think of APIs as contracts.

The contract describes the shape of the data, the form of the endpoints, and the behavior of the API. The client and the provider both agree to this contract.

However, the owner adds a new field when business requirements change or when they fix a bug. It means that API contracts change.

And versioning is how we say:

Here’s the old contract, still valid.

Here’s the new contract, with improvements.

There are three paths forward as the API evolves:

1. Release a new version in a new location

This means creating /api/v2/orders while keeping /api/v1/orders around.

The users can use the old version as it is. And switch only when they want the new features. This approach is safe and straightforward for clients, but it creates a lot of work for the API owner.

The API owner has to maintain several versions at the same time. For example, fix bugs, apply security updates, or implement features on all supported versions.

Besides, this approach might become expensive and slow down future development.

2. Release a backward-compatible version

In this approach, the API changes in a way that doesn’t break existing clients.

This means additive changes, such as including new fields, optional parameters, or endpoints in a response. As everything works the same way as earlier, consumers don’t have to update anything.

This strategy allows gradual growth but might be limiting when large design shifts are necessary.

3. Break compatibility

In this scenario, the API changes require each client to upgrade.

Although it sounds like the worst option, sometimes it’s unavoidable. For example, there might be a need for a different data model, or a serious security flaw needs to be addressed. Or the original API design had issues they couldn't fix easily.

In reality, we need a mix of all three, based on the change type and its impact.

But before we go further, let’s understand these technical terms first:

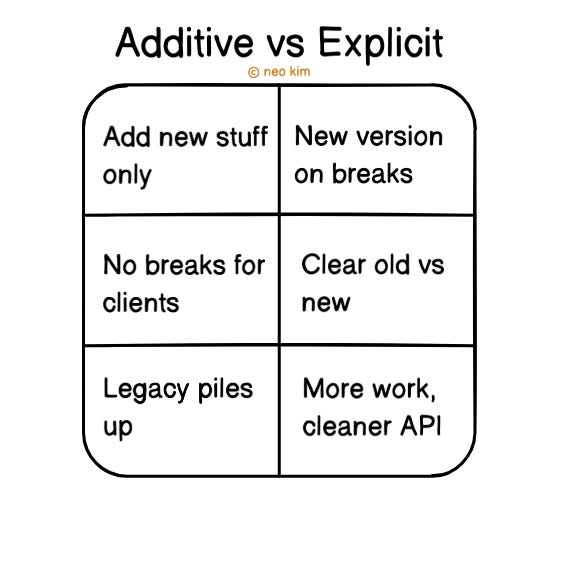

Additive versioning

It means additive changes to an API without incrementing its version.

You add new fields, parameters, or endpoints, but never remove or rename anything. It’s easy for consumers because they don’t have to change their integrations.

Explicit versioning

It means acknowledging when a change breaks compatibility.

You create a new version using a URL, header, or parameter. Thus making it possible to see old behavior in one version and new behavior in another.

I’ll walk you through different approaches to explicit versioning of an API, their benefits, and their drawbacks next.

Types of API Versioning

Let’s dive in:

1. Path-Based Versioning

This is one of the most common approaches.

https://coolapi.com/api/v1/ordersIt solves the problem of clarity and visibility because the consumer can easily understand which version they’re using by simply looking at the path.

Thus making it easier for new consumers to follow documentation and configure routing logic.

However, this clarity comes at the cost of stability. Here are some of its downsides:

Maintaining many versions creates redundancy and overhead for the API owner.

It pollutes URLs with version information.

Although this approach looks simple to implement, here’s the challenge:

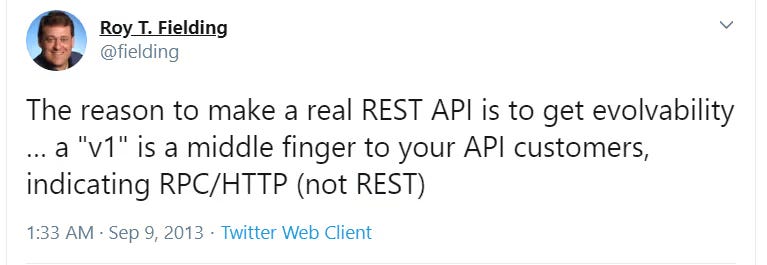

Roy Fielding, the creator of REST, said that it represents evolvability. That means the ability to change how a resource looks or behaves without changing its identity.

And Tim Berners-Lee said, “Cool URIs don’t change”. It means once you publish a URL, don’t change it. While people and systems should be able to rely on it forever.

If we link those together, versioning the URL path might become unnecessary.

So let’s just take a step back for a moment.

A REST API represents resources.

If

/api/orders/123points to an order, it should always point to that order, even if the response structure changes.But adding

v1orv2in the path (/api/v1/orders) breaks the principle, because it treats the same thing (an order) as if it had two unique identities.The resource (an order) hasn’t changed into something else, but only its representation has changed.

Here's how to best use path-based versioning:

Keep older versions alive for a transition period.

Announce clear deprecation timelines and provide migration guides.

Use shared libraries for common logic so that bug fixes don’t need to be copied everywhere.

Besides, HTTP itself provides mechanisms for communicating versioning and deprecation.

Here are two of the most useful techniques:

Sunset Header

An API uses the Sunset Header (RFC 8594) to signal when a version becomes unavailable.

For example,

Sunset: Wed, 01 Jul 2026 00:00:00 GMTIt tells the consumers that the current version is scheduled to retire on 01 July 2026. And combining this with headers like Deprecation:true, the client gets enough time to plan the migration.

3xx Redirects

Redirects are another simple way to guide clients from one version to another.

For example,

301 Moved Permanently

Location: /api/v2/ordersThis allows you to respond to a request /api/v1/orders with a 301 status code and a Location header, which specifies where the resource can be found.

Thus helping the consumers who don’t update their code right away by guiding them to the newest version.

But redirects work well when endpoints have changed only a little; otherwise, clients will need code changes.

2. Query Parameter Versioning

This approach keeps the base URL stable and includes the version as a URL parameter.

https://coolapi.com/api/orders?api-version=1.2.3It solves the flexibility problem at the resource level.

Here are some of its advantages:

URL remains stable.

The API owner can version endpoints or even individual resources without changing the overall API structure.

The consumer doesn’t have to update the base URLs, and different versions can coexist on the same path.

But this approach has its downsides. Here are some of them:

Many parameters can make it messy.

Routers rely on paths, not query strings; so you’ll need custom logic in the gateway or application to handle different versions.

Documentation has to be precise; otherwise, consumers may forget to include the query parameter and end up confused.

Caching becomes difficult because of cache pollution, misconfiguration, or wrong cache hits.

There’s a risk of consumers receiving the wrong version, as intermediate servers might ignore query parameters.

Here are some best practices for query parameter versioning:

Configure your CDN or cache to always include the query parameters in the cache key.

Document the parameters in each example call and check their presence on the server side to avoid silent issues.

Normalize query strings where possible to avoid duplicate cache entries. For example, treat `

?version=2and?version=02`as the same.

Although this approach gives you resource level control, it might complicate your codebase and caching strategy.

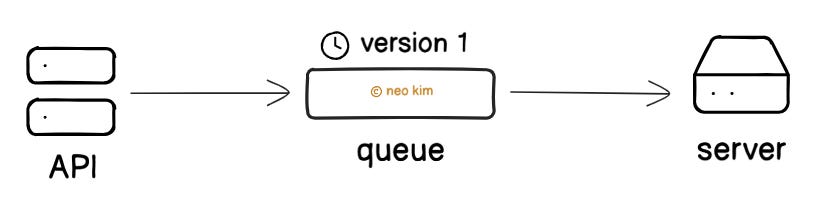

3. Message Payload Versioning

This technique includes the version as part of the request and response body itself.

{

“version”: “v1",

“data”: {

“id”: 123,

“status”: “shipped”

}

}Payload versioning enables the management of long-lived data in asynchronous systems. It means the system stores the payload with version information for later replay in event-driven or queue-based architectures.

For example,

You publish an event

{ “version”: “v1”, ... }to a queue.A service reads it right away or maybe 1 year later.

Because the message includes the version, the service quickly understands which format (schema) to use for deserialization.

However, this approach mixes concerns because versioning is part of business data.

Besides, the consumer has to understand and process versions (schemas) correctly. This adds extra complexity for REST APIs with short request/response lifecycles.

Here’s how to best use message payload versioning:

Use it only for asynchronous or event-driven systems.

Treat messages as fixed facts and create schema registries. This helps consumers safely de-serialize old formats.

Only use payload versioning if you store and reuse messages later (like in queues or logs).

For standard REST APIs, where responses are used immediately and then discarded, it just makes things harder.

4. Header-Based Versioning

This approach passes the version information in the request headers.

GET /api/orders

api-version: 2Another way is to version APIs through the Accept header.

The client specifies the resource version by requesting a specific media type. This is known as media type versioning.

For example,

Accept: application/vnd.example+json;api-version=2

Accept: application/vnd.github.v2+jsonThe API will then respond with the resource formatted for version 2 of the contract.

Here are some advantages of header-based versioning:

Allows clients to upgrade to new API versions at their own pace.

Keeps URIs stable and self-describing.

Aligns with HTTP semantics as metadata belongs in headers.

However, this approach has its downsides. Here are some of them:

Harder to debug, log, and cache as version information isn’t visible in the URL.

Some proxies or middleware might strip or block custom headers if not set up properly.

Besides, caching gets tricky when the version is in the Accept header.

CDNs, reverse proxies, and browsers might not know that different headers mean different versions. To solve this, you add a Vary: Accept header. It tells the cache to keep separate copies for each version and not to mix them up.

Header-based versioning may look hard at first, but it’s the cleanest long-term choice.

Your URLs stay stable, while versions are handled in headers. This keeps APIs consistent, avoids clutter, and follows REST principles. You need extra setup for caching, but the payoff is a smaller, easy-to-maintain API with less technical debt.

Now that we’ve covered versioning types, let’s explore versioning formats.

Versioning Formats

A versioning format is the way you label API versions to show what changed or when it changed.

1. Semantic Versioning

Semantic Versioning (SemVer) uses the format MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH. This helps to describe the changes included in a release.

MAJOR: Breaking changes (clients must actively migrate).

MINOR: Backward-compatible changes (new fields, endpoints).

PATCH: Bug fixes only.

For example, 2.4.1 indicates the second major release, fourth minor, and first patch.

This format gives consumers expectations:

1.9 → 2.0 is a big deal.

But 2.4 → 2.5 should be safe.

2. Calendar Versioning

Calendar versioning (CalVer) uses dates instead of numbers.

For example,

Ubuntu 24.04: released in April 2024 (YY.MM).

Python 3.12.20231001: released on 1 October 2023 (YYYYMMDD).

This format tells you the release date, which makes it easier to track freshness rather than compatibility.

3. Hash Versioning

Hash versioning (HashVer) uses hashes (like Git commit IDs) instead of numbers or dates. It points to the exact state of the code at a specific time.

For example,

v-237a2b4f: shortened Git commit hash of the build.

This format is precise for traceability, but harder for humans to understand changes.

Case Studies

It’s one thing to talk theory, but let’s look at how companies are designing their APIs:

1. Stripe

Uses header-based versioning with a

Stripe-Versionheader.New accounts are automatically “pinned” to the latest version.

Versions are in (CalVer) date-based format:

Stripe-Version: 2023-10-16.Most changes are backward-compatible; breaking changes are rare and controlled.

Clients can override the version on a per-request basis to test or migrate.

URLs stay clean as the versioning information lives in headers.

Stripe’s approach makes upgrades safe and client-driven. This aligns well with the principle: don’t break your consumers without their consent.

2. GitHub

Also uses header-based versioning with date identifiers (

X-GitHub-Api-Version: 2022-11-28).The base URL never changes: https://api.github.com

They support each version for at least 24 months, giving consumers time to migrate.

Additive changes roll out to all versions; breaking changes trigger a new version.

Keeps URIs stable, avoids version churn, and treats versions as snapshots in time.

If the header is missing, the API defaults to the latest version.

GitHub’s approach offers stable URLs and predictable migrations while reducing unnecessary versions. It highlights another philosophy: think of your API as incremental snapshots in time.

Let’s keep going!

When to Increase the Version?

There’s no fixed rule. Raise a new version only when the API contract changes meaningfully.

Ask yourself:

How many consumers depend on this?

Will the change break them?

Do SLAs or legal obligations apply?

Can you maintain many versions?

Be pragmatic; don’t version every deployment. Do it only when the change affects consumers.

Tooling for API Versioning

Versioning isn’t just about design. It also needs tools for routing, documentation, and consistency.

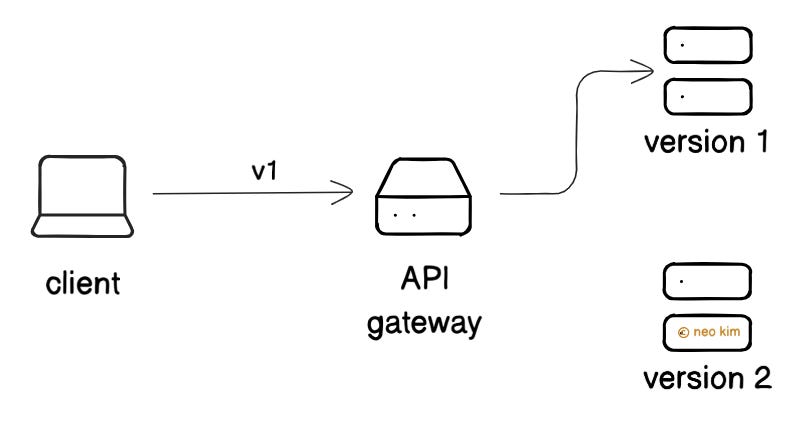

1. API Gateway

An API gateway manages traffic and routes requests to the correct services. It makes it easy to run different API versions in parallel.

Some examples: Kong API, Apigee, AWS API Gateway, Azure API Management.

You can keep

/v1/ordersactive while routing/v2/ordersto a new backend until consumers migrate.

2. Documentation Frameworks

Documentation shows consumers which version they’re using and what changed.

A documentation framework is a tool that helps you write and publish clear API docs so consumers know how to use different versions.

Some examples: OpenAPI / Swagger, Postman, Redoc.

You can publish documentation for both old and new API versions, and tools like Swagger will simply show what changed between them.

3. Versioning Libraries

Libraries reduce boilerplate and enforce consistent versioning across endpoints.

Some examples: .NET API Versioning, Spring Boot guides, Express.js middleware.

It lets you define versions in routes or headers, and send requests to the right version of your API automatically.

These tools don’t replace a strategy, but make it easy to manage versions at scale.

When to Use Which Strategy

There’s no single “best” way to version APIs. Each strategy solves a unique problem.

The right choice depends on your context:

Path-based versioning: internal systems where you control all consumers.

Query parameter versioning: resource-level flexibility, and can tolerate routing complexity.

Header-based versioning: safest for external or long-lived clients you don’t control.

Payload versioning: event-driven systems where messages are replayed later.

And with version formats:

SemVer: shows impact (breaking, additive, bug fix).

CalVer: shows freshness (release).

HashVer: shows traceability (commit or build).

The bottom line:

The additive strategy is good enough for most use cases.

So pick the strategy that causes the fewest surprises to consumers. Stability and clear migration paths build trust. That trust is more valuable than any technical detail.

👋 I’d like to thank Irina for writing this newsletter!

Also try her blog & courses: Irina Codes and Irina’s Courses.

It’ll help you become a better software engineer.

Subscribe to get simplified case studies delivered straight to your inbox:

Neo’s recommendation 🚀

Try Ashutosh’s newsletter to get deep dives on system design, AI, and software engineering.

Want to advertise in this newsletter? 📰

If your company wants to reach a 170K+ tech audience, advertise with me.

Thank you for supporting this newsletter.

You are now 170,001+ readers strong, very close to 172k. Let’s try to get 172k readers by 10 October. Consider sharing this post with your friends and get rewards.

Y’all are the best.

Block diagrams created with Eraser

Every successful API needs versioning.

It is also a good practice to monitor the number of clients still using older versions and log failed requests that may be due to version mismatches.

That gives guidance about when to sunset old versions.

Great Summary!

I appreciate this post. I think I understand better now