How Kafka Works

#91: Learn Everything About Apache Kafka’s Architecture, Including Brokers, KRaft, Topic Partitions, Tiered Storage, Exactly Once, Kafka Connect, Kafka Schema Registry and Kafka Streams

Get my system design playbook for FREE on newsletter signup:

This post outlines the Kafka architecture.

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Open any article about Kafka today, and you will see the same words being used to describe it:

“It’s an open-source, distributed, durable, very scalable, fault-tolerant pub/sub message system with rich integration and stream processing capabilities.”

While it’s true, it isn’t helpful for a novice reader being introduced to Kafka for the first time. Today, we will explain Kafka by precisely breaking down what every word in that definition means. Every definition will start with the 💡 symbol. At the end, you will have a complete high-level understanding of Apache Kafka.

I want to introduce Stanislav Kozlovski (“The Kafka Guy”) as a guest author.

He’s an Apache Kafka committer and software engineer who worked at Confluent (the Kafka company) during its hypergrowth period.

Check out his newsletter and social media:

2 Minute Streaming (Flagship newsletter)

Currently, he has taken a break from engineering to consult companies and write extensively about Apache Kafka and data engineering.

Apache Kafka

Apache Kafka is one of the most popular open-source projects in the data infrastructure space. It is a standard tool in every data engineer’s catalog, used by over 70% of Fortune 500 companies and 150,000 organizations.1

Kafka is a messaging system that was originally developed by LinkedIn in 2010. In 2011, it was open-sourced and donated to the Apache Foundation.2

💡 open-source (1/8)

Today, Confluent is a public company and widely known as the company behind Kafka. It has expanded its business to offer a more complete data streaming platform on top of Kafka.

Nowadays, Kafka is more than a simple messaging system: it’s a larger ecosystem of components that form a streaming platform3. It is frequently called the swiss army knife of data infrastructure.

Onward.

CodeRabbit: Free AI Code Reviews in CLI (Sponsor)

CodeRabbit CLI is an AI code review tool that runs directly in your terminal. It provides intelligent code analysis, catches issues early, and integrates seamlessly with AI coding agents like Claude Code, Codex CLI, Cursor CLI, and Gemini to ensure your code is production-ready before it ships.

Enables pre-commit reviews of both staged and unstaged changes, creating a multi-layered review process.

Fits into existing Git workflows. Review uncommitted changes, staged files, specific commits, or entire branches without disrupting your current development process.

Reviews specific files, directories, uncommitted changes, staged changes, or entire commits based on your needs.

Supports programming languages including JavaScript, TypeScript, Python, Java, C#, C++, Ruby, Rust, Go, PHP, and more.

Offers free AI code reviews with rate limits so developers can experience senior-level reviews at no cost.

Flags hallucinations, code smells, security issues, and performance problems.

Supports guidelines for other AI generators, AST Grep rules, and path-based instructions.

Kafka’s Story

Why did Kafka become so widely used?

It solved a very important problem - the problem of data integration at scale. LinkedIn had to connect different services to one another. A naive way of achieving this would be to create many custom point-to-point integrations (called data pipelines) between each service. That would have resulted in an O (N^2) mess that would break often and be impossible to maintain when N is in the hundreds.

Apache Kafka flips this problem on its head. Instead of creating custom pipelines per connection, it encourages organizations to:

Store their data in a central location (Kafka)

Use a single standard API (the Kafka API)

Have applications subscribe and consume this data in real time

This decouples writers from readers, as writers simply publish to Kafka, and readers subscribe to Kafka.

The data gets durably persisted to disk for a limited amount of time (e.g., 7 days). Kafka is ideal and was built with read-fanout use cases in mind, where the same message needs to get read by multiple systems. As such, it’s common for the system’s read throughput to be a multiple of its write throughput.

💡 pub-sub messaging system (2/8) - this is what a pub/sub messaging system is

With Kafka, organizations don’t need to maintain dozens of fragile custom point-to-point pipelines that break whenever a single VM restarts. The data can be written to Kafka once and read as many times as necessary by whatever system needs it.

In this article, we won’t talk further about the use cases of Kafka. If you’re more interested in the reason behind Kafka, I recently covered in-depth why LinkedIn created Kafka. It made the front page of Hacker News.

✅ Check it out here.

The Basic Kafka Concepts

Okay, let’s dive into Kafka now! To truly understand the system, we need to start from the basics.

Let’s examine its core data structure:

The Log Data Structure

Kafka is built upon the simple log data structure.

It is append-only; you can only add records to the end of the log (no deletes or updates allowed). Reads go from left to right, in the order the records were added.

Each record in the log has a unique monotonically increasing number called an offset. The offset refers to the record and denotes its order.

The API of the log data structure is very simple:

Kafka keeps the log structure on disk. The log’s sequential operations work very well with HDDs. Hard drives offer very high throughput for sequential4 reads and writes. This differs from random reads and writes, where HDDs don’t perform well.

Records

{record, message, event}: an entry in the log. I use these words interchangeably when describing data in Kafka.

Each message is essentially a key-value pair; it consists of a `byte[] key` and a `byte[] value` (although other metadata like offset, timestamp, and custom headers exist too). The key is optional; it is valid for a message to only have a value.

The key thing to remember is that the key/value pairs are raw bytes.

Kafka does not inherently support types (e.g., int64, string, etc.) nor schemas (specific message structures).

It is the client-side code’s responsibility to apply schemas:

When writing: producer clients convert (serialize) the objects into bytes.

When reading: consumer clients parse (deserialize) the raw bytes from the network into the object.

Topics & Partitions

Topics

One log is not enough. You want to separate your data into categories. Just as in a database, you would create separate tables for user accounts and customer orders; in Kafka, you would create separate topics.

It’s common for a Kafka cluster to have hundreds to thousands of topics.

Partitions

Kafka is a distributed system designed to scale much further than what a single machine can handle. As such, it uses sharding.

A topic is sharded into one or more partitions.

Each partition is a separate instance of the log data structure.

While a topic can have just one partition, it’s very common for it to have dozens, since this helps with parallelization of reads (more on that later).

Clients & The API

Kafka doesn’t use HTTP. It uses its own TCP-based protocol. This means that you need more custom code to send and receive requests; you can’t just use any HTTP library.

Kafka provides its own libraries that implement the underlying protocol. The main clients you’d care about are the Producer and the Consumer.

Producer: the class that’s used for writing data to Kafka

Consumer: the class that’s used for reading data from Kafka

The Apache Kafka project offers a Java library that implements these:

import org.apache.kafka.clients.producer.KafkaProducer;

import org.apache.kafka.clients.consumer.KafkaConsumer;The Producer class allows you to send messages to a topic. You can explicitly choose the partition or allow Kafka to do it automatically for you.

The Consumer, on the other hand, lets you subscribe to and read the stream of messages coming in from a topic (or specific partition):

This is simply the most important API I can show you concisely; a lot more exist. Kafka may seem simple, but it has many details to learn to be effective with it.

Kafka as a Distributed System

Brokers

Apache Kafka is designed to be a distributed system - one meant to scale horizontally by adding more nodes. As such, any normal deployment of Kafka consists of at least three nodes.

Broker: an instance of the Kafka server. This is what we call a node in the system.

Cluster: all the brokers in the system.

💡 distributed (3/8)

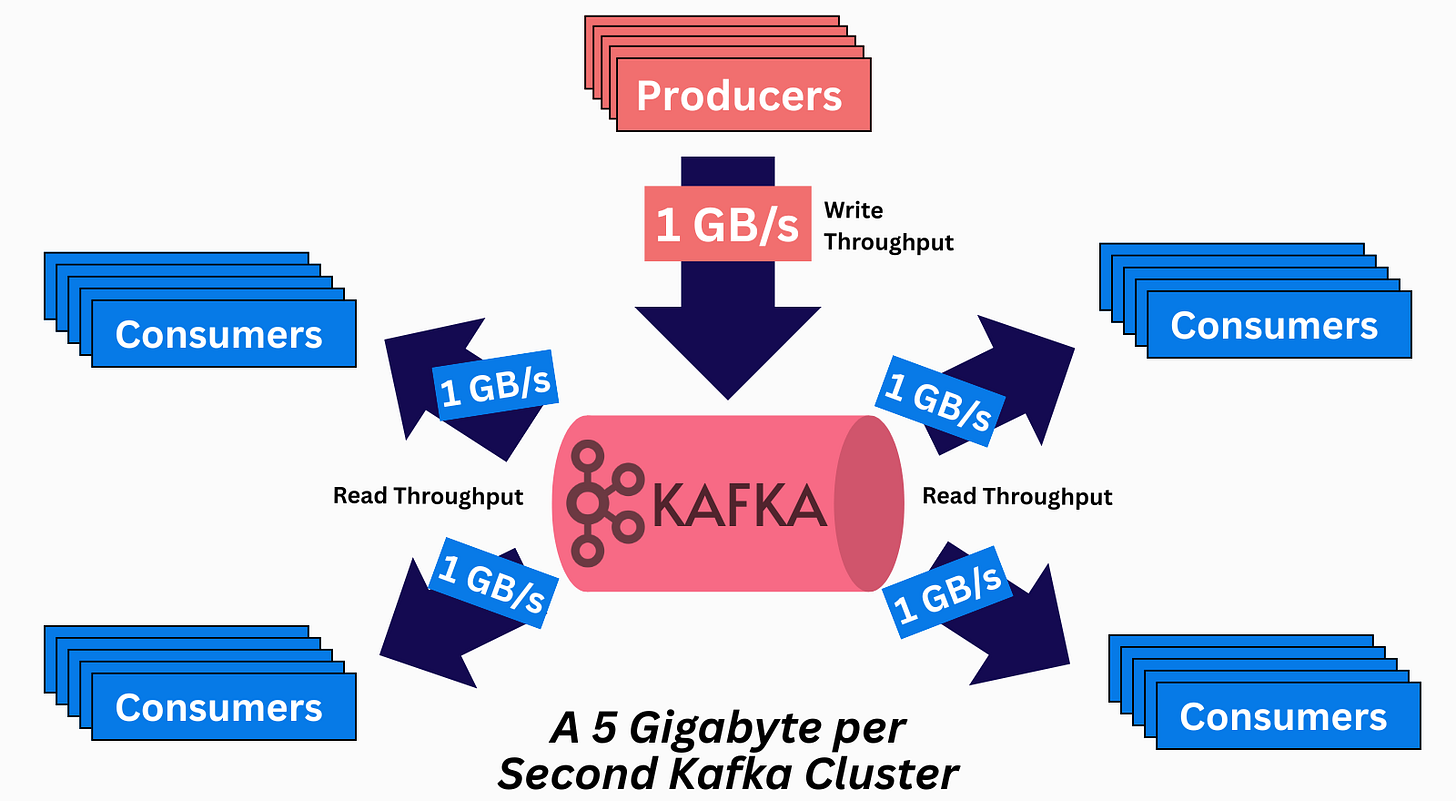

Scalability

Kafka has a ton of interesting performance optimizations (more on this in another article). Its greatest strength is its horizontal scalability.

💡 scalable (4/8)

The Log data structure is key to Kafka’s scalability - writes on it are O(1) and lock-free. This is because records are simply appended to the end and cannot be updated, nor individually deleted.

Messages within a partition are independent of each other. They have no higher-level guarantees like unique keys. This reduces the need for locking and allows Kafka to append to the Log structure as fast as the disk will allow.

Because each partition is a separate log, and you can add more brokers to the cluster, your scale is limited by how many brokers you can add.

Nothing theoretically stops you from having a Kafka cluster that accepts 50 GiB/s of writes and then scaling it 2x to 100 GiB/s.5

Replication

A partition in Kafka doesn’t live only on one broker - it is replicated across many.

A configurable setting (called replication factor) denotes how many copies should exist. The default and most common is three.

In other words, we have three copies (called replicas) of the Log data structure. These replicas live on the disks of different brokers.

Replication is done for many reasons, one of which is data durability6: when three copies of the data exist, one disk failing won’t lead to data loss.

In modern cloud deployments, brokers are spread across different availability zones. This ensures very high durability and availability. Even in the unlikely event of a whole data center burning down, the Kafka cluster would still survive.

💡 durable (5/8)

Leaders

Once you start maintaining copies of data in a distributed system, you open yourself to a lot of edge cases. Keeping new data in sync is tricky. The copies must match, and the system needs to somehow agree on the latest state.

There is a whole class of complex algorithms in computer science called distributed consensus, which handle this.

Kafka uses a straightforward single-leader replication model. At any time, one replica serves as the leader. The other two replicas act as followers (i.e., hot standbys).

Only the leader accepts new writes - it serves as the source of truth of the log. The followers actively replicate data from the leader. Reads can be served from both the leader and its followers.

When a broker node goes offline, the system notices it. Other brokers then take over the leadership of the partitions the dead broker led. This is how Kafka offers high availability.

💡 fault-tolerant (6/8)

The Metadata Log

In a distributed system, all nodes must agree on the latest state of the cluster. Brokers must coordinate on certain metadata changes, like electing a new leader. This is again a distributed consensus problem. Because it’s too complex for the purposes of introducing Kafka, we will simply gloss over how Kafka solves it.

Kafka uses a centralized coordination model7. The central coordinator is none other than… a log.

Kafka durably stores all metadata changes in a special single-partition topic called __cluster_metadata. This storage model inherits all the benefits from topics. It gets fault-tolerance, durability, and most importantly for metadata, ordering.

Each record in the log represents a single cluster event (a delta). When replayed fully in the same order, a node can deterministically rebuild the same cluster end state.8

Here is a visual example of how it works in Kafka:

In other words, the cluster metadata topic partition is the source of truth for the latest metadata in Kafka.

Every broker in the cluster is subscribed to this topic. In real time, each broker pulls the latest committed updates. When a new record is fetched, the broker applies it to its in-memory metadata. This builds the broker’s idea of the latest state of the cluster.

If every broker is a follower of the partition, a natural question arises - who is the leader? What node gets to decide what new metadata is written to this partition?

Controllers

Controllers serve as the control plane for a Kafka cluster. They’re special kinds of brokers that don’t host regular topics - they only do specific cluster-management operations. Usually, you’d deploy three controller brokers.

At any one time, there is only one active controller - the leader of the log. Only the active controller can write to the log. The other controllers serve as hot standbys (followers).

The active controller is responsible for making all metadata decisions in the cluster, like electing new partition leaders (when a broker dies), creating new topics, changing configs at runtime, etc.

Most importantly, it’s responsible for determining broker liveness.9

Every broker issues heartbeats to the active controller. If a broker does not send heartbeats for 6 seconds straight, it is fenced off from the cluster by the controller. The controller then assigns other brokers to act as the leaders for the partitions the fenced (dead) broker led.

The careful reader will now ask:

If the active controller is responsible for electing partition leaders, who’s responsible for electing the

__cluster_metadataleader?

The __cluster_metadata partition is special. A custom distributed consensus algorithm is used to elect its leader.

KRaft

Leader election in a distributed system is a subset of the consensus problem. Many consensus algorithms exist, like Raft, Paxos, Zab, and so on.

Kafka uses its own Raft-inspired algorithm called KRaft (Kafka Raft).

KRaft has two key roles:

Elect the active controller 👑

The controller nodes comprise a Raft quorum

The quorum runs a Raft election protocol to elect a leader of the

__cluster_metadatapartition. The leader of that partition is the active controller

Agree on the latest state of the metadata log

Metadata updates are first appended to the Raft log on the active controller.

They are marked committed only when a majority of the quorum has persisted them.

The active controller determines the leaders for all the other regular topic partitions. It writes it to the metadata log, and once committed by the controller quorum, the decision is set in stone.

In other words, the way leader election in Kafka works is:

Leader election between the controllers (picking the active one) is done through a variant of Raft (KRaft)

Leader election between regular brokers is done through the controller.

KRaft is a relatively recent algorithm in Apache Kafka. For many years, Kafka used ZooKeeper. Back then, there was just one controller. It performed the same tasks as today, but critically also had the responsibilities of a regular broker. Its decisions were persisted in ZooKeeper, which used the Zab consensus algorithm behind the scenes.

This coordinator-based leader election model differs from other systems. For example, RedPanda10 uses a separate Raft quorum per partition.

Other Features That Set Kafka Apart

Data Retention

A key motivation in Kafka’s design was to add the ability to replay historical data and decouple data retention from clients. Alternative messaging systems would store messages as long as no client has consumed them, and once consumed, delete them.

Kafka flips this model - it offers a simple time-based SLA as the message retention policy. A message is automatically deleted if it has been retained in the broker longer than a certain period, typically 7 days. The fact that the Log data structure’s O(1) performance doesn’t degrade with a larger data size makes this feasible.

Through this model, Kafka offers the feature of replayability - the ability to reprocess old historical messages. That is extremely useful in cases where, for example, a consumer has had a dormant bug in it for a while and erroneously processed messages. When the bug is fixed, the correct logic can be rerun on the same messages.

Tiered Storage

Unfortunately, at scale, it becomes extremely tricky to manage so much historical data. A cluster with 1 GB/s of producer bandwidth would collect 1,772 TB worth of data across the cluster11. Even spread across 100 brokers, it’s still 17TB worth of data that each broker would have to host on its disk.

With so much state, a lot of problems start piling up:

❌ The system becomes inelastic. This happens because any action or incident requires a massive amount of data to be moved. That takes a long time.

❌ Further, the way the cloud is priced - durably hosting data yourself on HDDs tends to cost 10x more than storing it in S3.

The Kafka community found an ingenious way to solve all these problems with one simple idea → outsource them to S3.

While it may sound overly simple or lazy, it is an extremely elegant solution. S3 is a marvel of software engineering - it is maintained by hundreds of bright Amazon engineers. It is most likely the largest scale storage system known to man.

Kafka uses a pluggable interface to store cold data in a secondary storage tier. All three cloud object stores are supported as the secondary tier, and you are free to extend it further.

In essence, the data path in modern Kafka looks like this:

Hotset Tier: Write a message to a Kafka broker, which gets replicated across the replicas in the cluster. The message is stored on disk across all three nodes.

The message is asynchronously offloaded to S3 (the secondary cold tier)

Cold Tier: After a configurable amount of time (e.g., 12 hours), the message is deleted from the brokers. Its only source of truth is left in S3. It expires from S3 after a separate configurable period.

You can still read the cold historical data from Kafka using the regular APIs. The only change is that the broker now fetches it from S3 instead of its own disk.

This results in slightly higher latencies when fetching historical data, but can be alleviated through caching. Latency for hot data can improve because it makes it cost-effective to deploy performant SSDs (instead of HDDs). Throughput remains the same very high number. Kafka as a system becomes much more elastic because it no longer needs to move massive amounts of data whenever new brokers are added or removed.

Storing large amounts of data in Kafka also ends up becoming more than 10x cheaper.

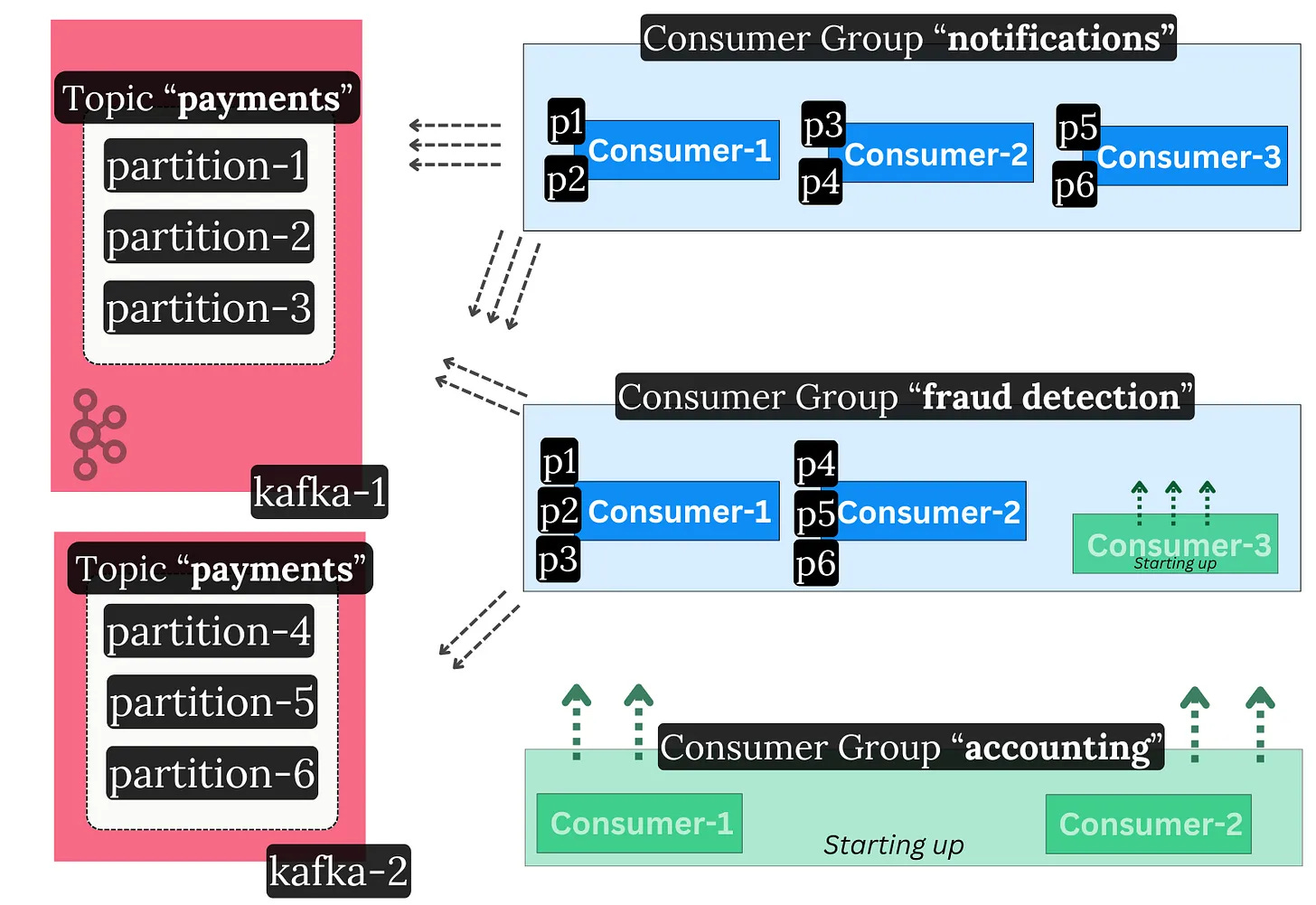

Consumer Groups & Read Parallelization

Recall that the log is read sequentially and in order:

A topic is split into partitions because it’s Big Data™ - a single node shouldn’t be able to consume the whole topic. You need many consumers to handle the high volume of topic data.

Only one consumer is meant to read from a partition at a time. This is done to ensure message order without needing locks.

These consumers need to coordinate on how to split partitions between each other.

At the same time, Kafka’s goal is to allow parallel consumption (multiple readers) of the same partition(s) for high read-fanout cases.

Kafka addresses this through consumer groups. These groups are a set of consumer client instances (typically on separate nodes) that operate as one coherent unit. They distribute the work among themselves.

Each consumer group reads topics independently at its own pace. Consumers within the same group split the partitions between each other.

Consumer Groups support dynamic membership - you can scale consumption up or down by adding or removing members at runtime.

In essence, read throughput in Kafka can be scaled in two different ways:

Add more consumers to your group

e.g., your topic went from 10 MB/s to 20 MB/s of throughput, and your two existing consumers can’t keep up. Add more so they take up the extra load.

Add more consumer groups

e.g., your topic is being consumed, but you’d like a new, separate application type to process the data too. For example, a nightly accounting job wants to catch up with the last day’s worth of payments.

The Consumer Group Membership Protocol

Consumers within a group form a distributed processing system. Unsurprisingly, we hit more distributed systems’ problems - how do we coordinate the consumers? They need to:

Establish consensus on progress (up to what offset did they read to)

Handle liveness (did a consumer go offline, and how do we take over its work)

Handle dynamic membership (did a new consumer come online)

Distribute work between themselves (which consumer will take which partition)

Kafka consumers within the same group don’t talk to each other. They coordinate indirectly through a Kafka broker. The broker that leads a certain group is called the Group Coordinator.

Kafka again uses a centralized coordination model - the Group Coordinator makes the decisions. Consumers heartbeat to the coordinator and, through a pull-based model, inform themselves of what work they should do.

The __consumer_offsets Topic

The Group Coordinator also acts as the “database” which stores the progress of each consumer.

Consumer Groups store a simple mapping of `{partition, offset}` in a special Kafka topic called `__consumer_offsets`. This helps them save the progress on what record they have read up to.

When a consumer reads messages, it commits the offset up to which it has processed the log via the coordinator broker. This regular checkpointing allows for smooth failovers. In the event of failure, the consumer can restart and resume from where it ended, or another consumer can come and pick the work back up.

The special offsets topic has many partitions spread throughout brokers. Each group is associated with a particular partition. The leader of the particular partition that the group is associated with acts as the Group Coordinator for that group. In that sense, every broker in the cluster can act as a coordinator for some consumer group. This prevents hot spots where one broker handles all the consumer groups in the cluster.

The consumer group protocol is a critical part of Kafka.

It is generic enough to support other use cases beyond consumer groups. It therefore provides a way for external distributed systems to establish leader election and durably persist state through Kafka.

Keep this in mind: the next three systems we’ll discuss depend on the group protocol to work as distributed systems.

But first, a little about transactions:

Transactions & Exactly Once Processing

I will try to keep this brief because it can get pretty complicated - Kafka supports transactions. But they aren’t quite like database transactions - it’s more about message visibility control.

A transaction in Kafka means that:

A producer can send many messages. Those messages can go to different topics or partitions. They can also reach various brokers.

Those messages will atomically either be committed or aborted across all brokers.

Technically, this happens from the perspective of a consumer. In other words, the messages are still written to the topics, but consumers can be configured to skip non-committed ones. This is client-side filtering at work.

Marking transactions as committed or aborted is achieved through a two-phase commit protocol. It again relies on a centralized coordination model. A Transaction Coordinator broker makes this work. It’s pretty complex.

The important thing with transactions is that they enable message deduplication in common cases.

⚡️ Network/broker blips: if the network drops the broker response packets, or the broker restarts, the same producer client will idempotently12 write its message without creating duplicates.

💥 Producer client blips: if the producer itself restarts from a clean state, it will fetch its monotonically increasing ID and bump an epoch. This way, a potentially old zombie instance with the old epoch can’t interfere with the transaction.

This doesn’t remove all cases of duplicates. Edge cases from external systems can still exist.13

However, when reads and writes only involve Kafka (and no other external system), exactly once processing is possible.💡

This is actively supported and used in Kafka Streams, as we will cover shortly 👇

Other Kafka Components

The Apache Kafka GitHub project consists of a few components, two of which we already covered:

Kafka Core: the brokers, controllers, and coordinators (back-end).

Kafka Clients: the Kafka client libraries (producer, consumer).

These are two more that we will focus on now:

Kafka Streams

Kafka Connect

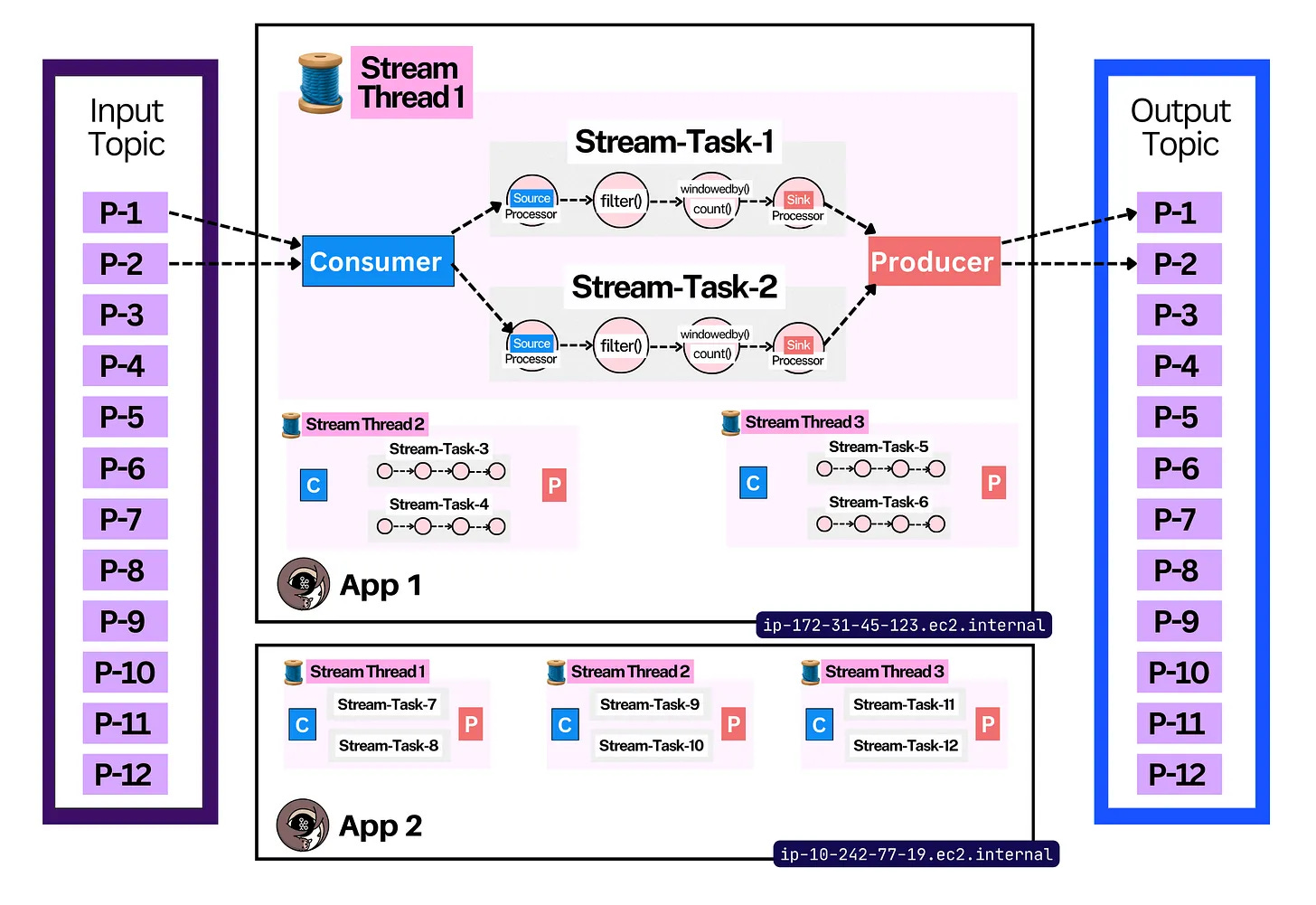

Kafka Streams

A stream processor is an application that:

continuously processes messages

works performantly and at scale

emits the results in real-time

supports complex stateful operations like windowed aggregations and joins of multiple streams of data14

Kafka Streams is a high-level client-side stream processing Java library for Kafka. It offers rich higher-level stream processing APIs that basically do this:

continuously read a stream of messages from a set of Kafka input topics

perform processing on these messages (map, filter, joins, sums, stateful window aggregations, etc.)

continuously write the results into an output topic

Here is a simple pseudocode example of its declarative API:

This code continuously counts the sum of human page views over the last minute and produces it in a new topic. Here is an example of what the Kafka topics would look like:

This API is intended to be used within your own Java applications. It works like the consumer. It helps you scale by spreading the stream processing work over multiple applications (just like consumer groups do). One difference is that it also lets you spread the work through threads. It uses the same consumer group protocol underneath to coordinate work between instances.

It is technically possible to achieve this with your own code using the simple producer/consumer libraries, but it’d be a lot of work. Kafka Streams is a higher-level abstraction above both clients with a ton of extra processing, orchestration, and stateful logic on top. 👌

Kafka Streams only works with Kafka. It takes input from a Kafka topic and sends output to another Kafka topic. This setup allows Kafka Streams to guarantee exactly once processing by using Kafka Transactions. Practically speaking, this means that it can atomically process data.

For example, it could read a set of payment messages in a Kafka topic, calculate the sum, and persist the result in another Kafka topic, with a 100% guarantee that no message was lost or double-counted in the process.

If interested in more, here is a quick introduction to Kafka Streams.

Schema Registry

Kafka does not support types (e.g., int64) nor schemas15. Messages are just raw bytes16. To process a message, like summing order payment values, you need to be able to parse the message structure and the exact value field. How is this achieved, then?

There’s no “official” way, because the open source Apache project does not support schemas. There is a common convention, though. That is to use an external HTTP service with a database that stores the schemas.

In practice, a Kafka topic acts as this database. It stores a simple pair of {schema, topic}. Kafka clients connect to the service, download the schema, and use it whenever they serialize/deserialize messages.

The first such registry was a source-available project by Confluent called Schema Registry. However, without official Apache support or a truly open-source license, the ecosystem has fragmented. There are many different service implementations17 today. Many Kafka users also opt to manage schemas in their own unconventional ways.

The way the end-to-end path conventionally works with schemas:

Producers decide on a schema, associate it with a topic, and register it in the registry

Producers then serialize the message in the correct structure (including the unique schema ID in the message) and write it to Kafka

Consumers download the message, parse the schema ID, then fetch (and cache) the schema from the registry

Consumers use the schema to deserialize the message

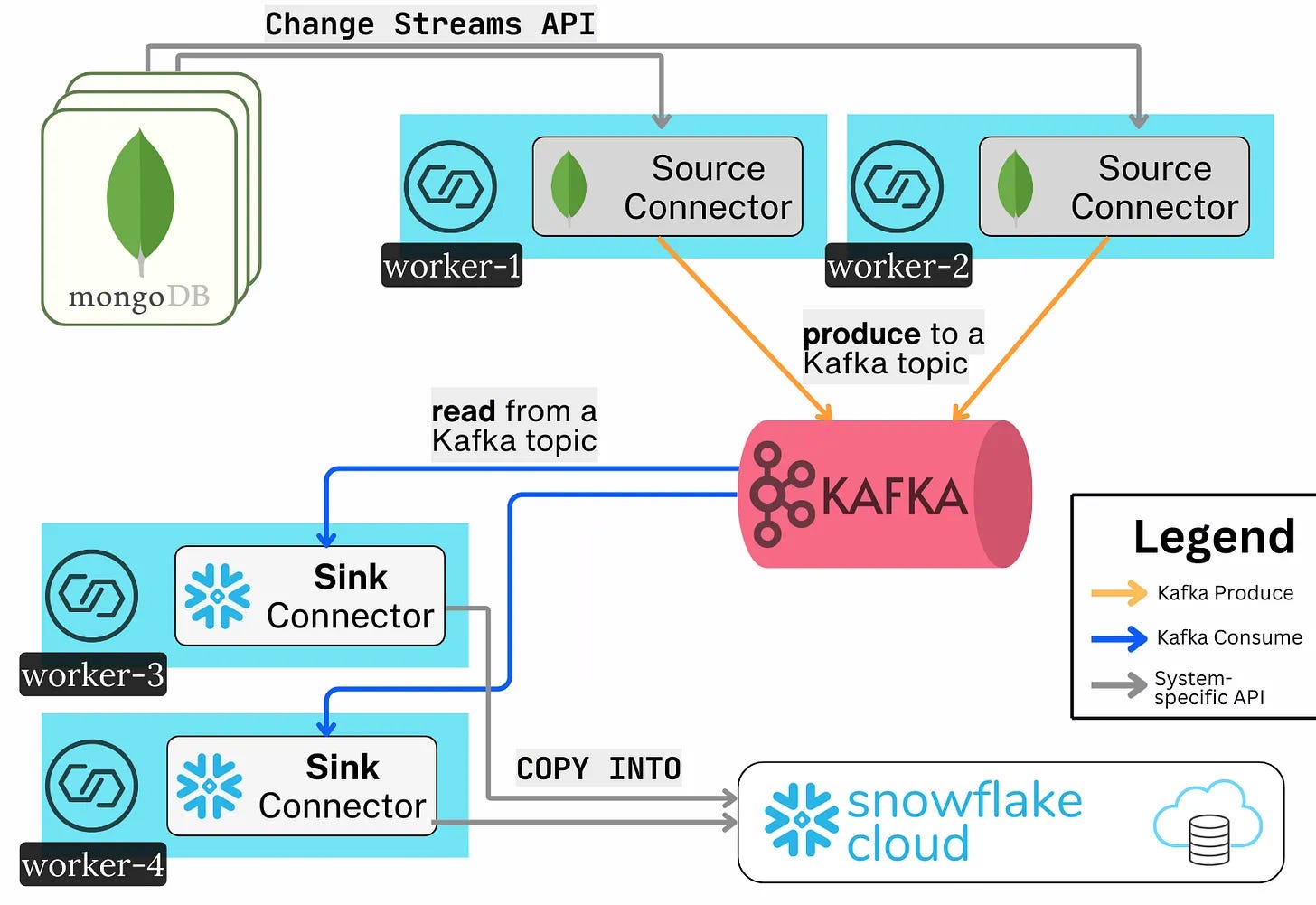

Kafka Connect

Kafka was created to solve LinkedIn’s data integration problem. It is meant to move data between different systems. This can be difficult because each system can have its own API, its own protocol (TCP, HTTP, JDBC, etc.), its own format (XML, JSON, Protobuf, Avro), and different compatibility guarantees.

Kafka Connect helps standardize this. Connect is both a framework (set of APIs) and a runtime for plugins that connect Kafka with external systems18.

For the end user, it’s a no-code/low-code framework to plumb popular systems to Kafka and back (think ElasticSearch, Snowflake, PostgreSQL, BigQuery).

This ensures a single, standardized way to integrate systems together. The tricky bits of code that guarantee fault-tolerance, ordering, and exactly-once processing are written once (in the form of plugins) and battle-tested.

Connect has three main terms one should know about:

Connect Workers: the simple nodes that form a distributed Connect Cluster

Connect Herder: a worker that acts as the manager of the cluster. It exposes a REST API with which users can check the status of tasks, start new ones, etc

Connectors: the plugins (or libraries) that run on the workers. They contain the code needed to integrate with other systems

A Source Connector reads data from an external system and writes it to Kafka (System->Kafka)

A Sink Connector reads data from Kafka and writes it to an external system (Kafka->System)

The end user spins up a cluster with several Worker nodes. They install the particular Connector plugin jars on these nodes. Then, they start the integration with a simple HTTP POST request.

This again forms another distributed processing system. The Herder leader election, general cluster membership, and the distribution of new tasks throughout the group of Workers are all done transparently via Kafka’s Consumer Group protocol.

Essentially, Connect is a lot of plugin-specific integration logic on top of the regular KafkaProducer and KafkaConsumer APIs. Hundreds of Connector plugins exist, which give Kafka its incredibly rich integration capabilities.

💡 rich integration (8/8)

🎬 Conclusion

With that, we’ve gone over all the important internals of Apache Kafka. I repeat the introductory sentence, which you can now hopefully understand much better:

💡 Kafka is an open-source, distributed, durable, very scalable, fault-tolerant pub/sub messaging system with rich integration and stream processing capabilities.

It achieves this through many internal details, including but not limited to:

The Producer & Consumer libraries & APIs

Topics, Partitions, and Replicas

Brokers and KRaft Controller Quorums

Idempotency, Transactions, and Exactly-Once Processing

Tiered Storage

Consumer Groups & the Consumer Group Protocol

Kafka Streams

Kafka Connect

Schema Registry

This is why Kafka is the Swiss army knife of data engineering.

It is a very active open-source project that is constantly evolving. A few notable features that are currently being worked on are:

Queues: the ability to read a partition with queue-like semantics. Queues have no ordering but allow for multiple consumers to read from the same log with per-record acknowledgement. This is different from Kafka’s exclusive one-consumer-per-partition model. In that model, consumers read data in order and only know “I’ve read up until this message”.

Diskless Topics: the ability to host topic partitions in a leaderless way. This happens by leveraging object storage (S3) as the data layer instead of brokers’ disks. This feature can cut cloud costs by 90%+ (!), further boost scalability, and simplify managing Kafka.

Iceberg Topics: the ability to store your Kafka data in an open table format (Iceberg) in a zero-copy way.

Many alternative proprietary systems compete with Apache Kafka. The one common denominator is that they all use the same Kafka protocol and API. They just implement it differently. These include, but are not limited to, Confluent Kora, AWS MSK, RedPanda, WarpStream, BufStream, Aiven Inkless, AutoMQ, and more.

The space is incredibly rich and rapidly evolving. If you’re further interested in the world of event streaming and Apache Kafka, make sure to stay in touch. 🙂

👋 I'd like to thank Stanislav for writing this newsletter!

Also subscribe to his newsletters: 2 Minute Streaming and Big Data Stream.

It’ll help you master Kafka quickly.

Subscribe to get simplified case studies delivered straight to your inbox:

Want to advertise in this newsletter? 📰

If your company wants to reach a 170K+ tech audience, advertise with me.

Thank you for supporting this newsletter.

You are now 170,001+ readers strong, very close to 171k. Let’s try to get 171k readers by 28 September. Consider sharing this post with your friends and get rewards.

Y’all are the best.

Apache®, Apache Kafka®, Kafka, and the Kafka logo are either registered trademarks or trademarks of the Apache Software Foundation in the United States and/or other countries. No endorsement by The Apache Software Foundation is implied by the use of these marks.

This adoption data is an estimation by Confluent, the company founded by the creators of Kafka. I have no good way to confirm it.

That’s why its official name is “Apache Kafka”, although we still often say Kafka for short.

A Streaming Platform means a system that allows you to store and process a large volume of streams of data. For example, a company like Uber has millions of drivers constantly streaming their GPS coordinates to Uber’s backend systems. A streaming platform can scale this data and process it in real time as it comes. This helps Uber make use of the data (e.g, recompute the route, figure out where there is traffic, etc).

A sequential read means reading bytes laid out contiguously on the physical drive. Random reads mean the opposite - you have to jump to different parts of the drive to read the bytes.

Theoretically, you can do this by using very good high-end hardware with ample networking capacity. An example could be 75 brokers each accepting 512 MiB/s of writes. Modern SSDs can do this without a problem. Practically speaking, it would be very hard to operate and require custom code. Therefore most prefer to split such workloads into many clusters.

Durability refers to long-term data protection - ensuring that data never gets lost or corrupted.

Centralized coordination in distributed systems means all the nodes rely on a single authority, like a coordinator or a leader. This authority makes decisions, enforces rules, and keeps the state consistent. Alternative interesting models include things like quorums, gossip, and CRDTs.

Stream-table duality is the simple idea that a stream of events and a table are two sides of the same coin. Any mutation to a table (update/delete/insert) is in itself an event. The table simply represents the end state of all events. If you start from scratch and replay all the events, you reach the same table.

Event-sourcing, on the other hand, is the design of a system around this log-based stream of events.

The ideas have their roots in materialized view theory in databases and in change data capture. (Some sources, if you’re extra curious: stream-table duality and event-sourcing)

Liveness is a tricky distributed systems term that basically means that the system will eventually make progress (won’t freeze up). In the context of broker liveness, it means that a dead broker will get fenced, so partitions don’t get stuck on a dead node. This allows the cluster to move forward. Liveliness technically also means that an alive broker will eventually be unfenced.

RedPanda is a C++ rewrite of Kafka, purpose-built to offer ultra-low latencies. It is fully compatible with the Kafka protocol & API. However, it takes some different design choices. For example, it uses a Raft quorum for each partition. It features a thread-per-core execution model based on the Seastar library (similar to Scylla, the C++ Cassandra rewrite). It is also simpler because it directly ships with a schema registry and HTTP proxy.

1 GiB/s * 60 (seconds) * 60 (minutes) * 24 (hours) * 7 (days) * 3 (replication) == 1,814,400 GiB == 1,771.875 TiB; Not to mention you want to run your disks with ample free space capacity (e.g., 50%) - you’d need to provision ~3500TB worth of disks!

Idempotency means not repeating the same action twice. If a “Create User Bob” request is sent twice, an idempotent system would create the user only once. In Kafka, this is achieved by associating a unique monotonically increasing ID with each message. So you could send the message (“Create-User-Bob, 1”) twice, but Kafka will accept it only once because of the unique ID. This is not foolproof, though, because the unique ID comes from the Kafka Producer client. Two producers can therefore create the same message with different IDs.

Most simply said, imagine you have an HTTP service receiving requests. The service processes the request “Create user Bob” and successfully produces the message to Kafka. Before the service responds with an HTTP response to the user, it crashes. The user then retries the same HTTP request, and the new service produces the same “Create user Bob” into Kafka. From Kafka’s PoV, this is fine because it sees both as separate messages. The HTTP service evidently does not support handling idempotent requests and exactly-once processing.

Stream processing - the easiest way to understand it is through the opposite extreme - batch processing. Imagine you are Tesla and are collecting data from your fleet of cars. At the end of each business day, you run a big report. The report joins data from multiple sources and creates a dashboard that an executive in Tesla sees. They use it to see summaries like the number of kilometers crossed, times they had to charge the Tesla, how often X feature was used. It runs once a day and calculates data after a cut-off date (e.g., end of day). Stream Processing would be the opposite - it would have the cars continuously emit data like their tire pressure (psi). It would then perform windowed aggregations on this data to understand, in real time, what’s happening to the car. If the tire pressure went from 45psi to 41psi over the course of 15 minutes, you’d know the tire is losing pressure. If the tire pressure went from 45psi to 20psi over the course of 10 seconds, you’d know you blew out a tire. Tesla could implement this example by deploying a lot of Kafka Stream jobs in their back-end. (assuming the data exists in Kafka)

A schema basically means the expected structure of your data. A database table has a very strict schema - you know what type each field is and what fields there are (e.g id BIGINT, name VARCHAR, cost DECIMAL, is_premium BOOLEAN). You can’t add fields or types that don’t match, like a string for an ID. A JSON object by itself is schemaless - you can modify it however you want and it’s still a valid JSON object (the only question is whether your server will accept it, and that depends on the modification). In the same way, a blob of bytes doesn’t have a strict structure - you can add any garbage in there. There is a project that adds a strict structure to JSON objects called JSON Schema. Similarly, there are projects that add strict structure to blobs of bytes (Protobuf, Avro). It’s important to have schemas because they are critical to validating and catching bugs in your data early.

I believe this was a big mistake by the project. Every important use case, like Connect, Streams, and general processing, must understand the data’s structure.

A few schema registry implementations are Karaspace (Apache-licensed), AWS Glue (proprietary), ApiCurio (Apache-licensed), Buf Schema Registry (proprietary), and Redpanda (mixed licenses).

A runtime here means that you deploy the Connect software, and then, via `curl`, schedule extra pre-defined code to run on top of it (plugins). A framework means that you’re free to write your own plugins that use the API if you’d like.

This article is so comprehensive. One can find their way round kafka with this .

This article is awesome. Explaining every capabilities of the tool so that we can go deeper as needed. As a beginner in kafka, this is very helpful. Thanks!