System Design Interview: Design Web Crawler and Search Engine

#124: System Design Interview

Share this post & I’ll send you some rewards for the referrals.

You type something in the Google Search bar and get instant results.

How does this work?

Today’s newsletter will teach you the architecture of search systems.

At a high level, a search system has two components: a web crawler and a search engine.

A web crawler crawls webpages and stores them in a datastore.

A search engine looks through the data in the datastore to answer user search queries.

Let’s start by understanding the system requirements…

Need public web data, without scraper headaches? (Partner)

SerpApi turns search results into predictable JSON with built-in scale, location options, and protection from blocks.

That’s why engineers use it to ship:

AI applications

Product research

Price tracking

SEO insights

All without maintaining scrapers or infrastructure.

(I’d like to thank SerpApi for partnering on this post.)

I want to introduce Mandeep Singh as a guest author.

He’s an author, educator, and software engineer with a strong passion for building simple, scalable systems. He authored the O'Reilly book "System Design on AWS" and supports others' learning and development by sharing lessons on Cloud and System Design on YouTube.

Checkout his work:

System Design on AWS Book (Also find on Amazon)

System Requirements

(There are two kinds of requirements: functional and non-functional.)

Functional requirements are functionalities from the user's perspective.

It includes:

Fetching top results for a search query.

Including the web page URL, title, and subtitle in each result.

Avoiding outdated results.

Search systems are large and support many functionalities. So let’s limit the scope:

Queries can only be done in English.

Exclude what, why, and how of machine learning components.

The system must follow certain constraints to maintain quality. These are called non-functional requirements (NFRs).

Key NFRs include:

Availability: System must be up and able to respond to search requests.

Reliability: System must return correct and consistent results.

Scalability: User traffic grows over time, so does the content on the internet. The system must handle this growth without performance issues.

Low Latency: Search results should be returned in milliseconds.

These requirements guide the system design. Another important factor is the expected scale, which directly affects design decisions.

Let’s estimate the system scale next…

Back of the Envelope: Understanding Scale

In system design interviews, it’s recommended to make some assumptions after discussion with the interviewer.

Here are some estimations:

Web crawler

The scale of a web crawler depends on how many pages it crawls.

Assume:

Active websites: 200 million

Average pages per website: 50

Now, for each website, there can be both internal and external redirects. The external redirects are part of 200 million.

Then, for internal redirects:

Total pages = 200 million × 50 = 10 billion pages

Now estimate storage:

Average page size: 2 MB

Total storage = 10 billion × 2 MB = 20 PB

NOTE: Web pages can include text, images, and videos. In practice, a crawler may store only the parts needed for search. This estimate assumes we store pages as-is, in the same format in which we download them.

Let’s look into the scale of the search engine system next…

Search engine

Assume Google scale traffic:

Searches per day: 8.5 billion

Searches per second: ~100,000

These rough numbers help shape the design choices.

Next, we’ll dive into the high-level system design…

High-Level System Design

We’ll design a scalable system and discuss the key components of each subsystem separately. Keep in mind that Google has evolved significantly to support this scale, and it is not possible to capture all details in this post.

We’ll first design the web crawler, and then move on to the search engine:

Web Crawler

The crawler needs an initial list of URLs to start with. These are called seed URLs.

There is no single source that contains all websites. So we start with well-known domains and discover new URLs as we crawl.

Here are several ways to discover new website URLs:

Create a platform for new website owners to submit their site details.

Retrieve the list of website links from the website being crawled.

New website URL queried by the user.

The crawler does not visit every website at the same rate. Some sites change frequently, while others rarely update.

The process of deciding how often to visit a website is called crawl scheduling (politeness). The component that decides which URL to crawl next is called the URL frontier.

1. URL Frontier Design

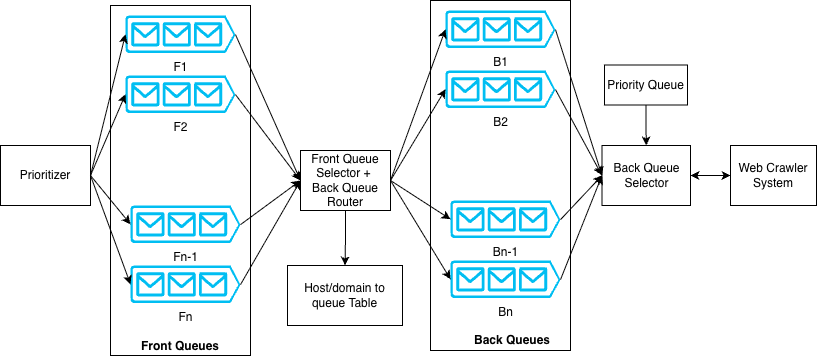

The design shown in Figure 1 is inspired by the Mercator crawler. It uses a two-stage queue system to handle both priority and politeness.

Here’s the architecture overview:

Front queues represent different priority levels. The prioritizer assigns a priority (for example, 1 to n) to each URL. Based on this value, the URL gets placed into a specific front queue. The front queue selector picks URLs using a weighted round-robin approach, so higher-priority URLs get chosen more often.

From the front queues, URLs move to the back queues. A domain-to-back-queue database ensures that all URLs from the same host (for example, example.com) go to the same back queue. This helps enforce politeness rules per host.

A priority queue (implemented as a min-heap) keeps track of when each host can be contacted again. There is one entry per back queue. The heap stores the next allowed fetch time for that host/domain.

The back queue selector removes the host with the earliest allowed time from the heap. It then fetches one URL from that host’s back queue. After the URL gets crawled, the system updates the heap with the next allowed fetch time according to politeness rules.

While Mercator provides a strong foundation, there can be bottlenecks at internet scale:

FIFO queues keep a fixed number of URLs in memory and store most URLs on disk to support a high crawl rate on commodity hardware. At a large scale, frequent disk reads and writes can become a bottleneck. More advanced disk-based algorithms (such as those discussed in IRLBot research paper) can help reduce this overhead.

Another issue is static priority and politeness logic. If a website becomes slow or starts returning errors, the crawler should adjust its crawl rate dynamically. Instead of fixed rules, the system should use adaptive politeness. HTTP response code could be an important factor in this decision.

For example:

HTTP 200: Crawl at normal rate.

HTTP 429: Reduce crawl rate and retry later.

HTTP 500: Retry only after a longer cooldown.

Many domains could share the same IP address (shared hosting, CDNs, cloud providers). Using a single back queue per host can cause skew or a hotspot. The solution is to enforce limits at both the host and IP levels.

For example:

hello.comcan be crawled once every 10 seconds.IP

192.168.1.2can be crawled up to 5 times per second across all domains hosted on that IP.

URL frontier acts on a continuous feedback loop. URL fetcher (Figure 2) reports metrics such as latency and error rate. URL frontier adjusts crawl rate and priority based on these signals.

For example:

If a website responds slowly, increase politeness (reduce crawl rate).

If there are repeated 500 errors, lower the website’s priority.

Once URL frontier selects a URL, the crawler visits the page. Before crawling, the system should check whether the page has already been fetched or modified. There is no benefit in fetching the same content repeatedly.

Next, let’s discuss URL duplication and content duplication handling...

2. Web Page Similarity and URL Duplication

A web crawler can run into infinite loops. This can happen if:

A page links to itself.

The same URL appears many times in different places.

URLs are generated dynamically in large numbers.

To prevent this, the crawler must detect duplicate URLs before crawling them.

URL Deduplication

How do we check if a URL was crawled?

One approach is to store all crawled URLs in a global lookup table (HashMap). As many crawler instances run in parallel, this lookup must be shared across machines. A distributed key-value database can be used for this purpose.

This lookup needs to be fast.

Disk-based databases increase latency because of disk reads. An in-memory system is faster but must handle very large amounts of data. The data can be partitioned (sharded) across many machines to scale.

We can use a Bloom filter to reduce memory usage.

A Bloom filter is a space-efficient data structure that checks whether an element already exists in a set. It’s probabilistic, that is:

If it says “no,” the URL definitely has not been seen.

If it says “yes,” the URL might have been seen.

This can sometimes cause a new URL to be skipped, but for large-scale crawling, this tradeoff is acceptable.

The URL set can be distributed across machines using consistent hashing. This ensures even distribution and supports adding or removing servers without major reshuffling.

Now let’s focus on content duplication…

Content Deduplication

Even if URLs are different, page content might be the same.

A simple word-by-word comparison is expensive and inefficient. Instead, crawlers compute a fingerprint of the page content. One common technique is Simhash algorithm, which generates a compact representation of the page.

Similar pages will have similar fingerprints, making duplicate detection efficient.

Handling Intentional Duplicates

Some websites intentionally publish the same content under different URLs.

Search engines support a canonical link element to handle this scenario. Website owners can specify the preferred URL for a piece of content. The crawler stores only the canonical version for indexing.

The bottom line:

URL deduplication occurs before crawling.

Content deduplication occurs after fetching the page.

Robots and Exclusions

Before crawling, the system must check whether the URL is allowed.

Web servers can define rules in the robots.txt file to control crawler access. The crawler must respect these rules. Also, the crawler may maintain its own blocklist for certain websites or regions.

After passing these checks and finishing the crawl, the system stores the page content.

Next, let’s discuss storage design…

3. Web Crawler Storage

The choice of database depends on what we want to store and what format.

Here are a few options:

Store the entire webpage as-is

This is like saving a webpage using “Save Page As” in a browser. The full HTML content is stored without modification.

Extract and store only the required data

The crawler processes the page and saves only useful parts, such as text and metadata.

Store the page in a document database

Since a webpage is essentially a document, it can be stored in a document database.

In our case, the data has no fixed structure, and we do not need to run complex queries on it. So the simplest approach is to store the entire webpage.

An object store, such as Amazon S3, is a good fit for this.

Object stores are scalable and highly durable, so we don’t have to worry about scalability and reliability. At a very large scale, some companies build and manage their own distributed storage systems, but that is a separate and complex topic.

NOTE: Colossus is Google’s distributed storage system. It replaced Google File System (GFS) and is designed to support Google’s massive scale.

Metadata Storage

We also need to store metadata. It includes:

URL

Location of stored content

Last crawled time

Status or crawl result

This requires a key-value style database, where:

Key = URL

Value = Metadata

A relational database could also work, but since we do not need complex joins or relationships, a distributed key-value store is more suitable. The data should be partitioned (sharded) for scale.

Now that we have covered the main crawler components, let’s discuss how these components work together to crawl the web…

4. Web Crawler Components Coordination

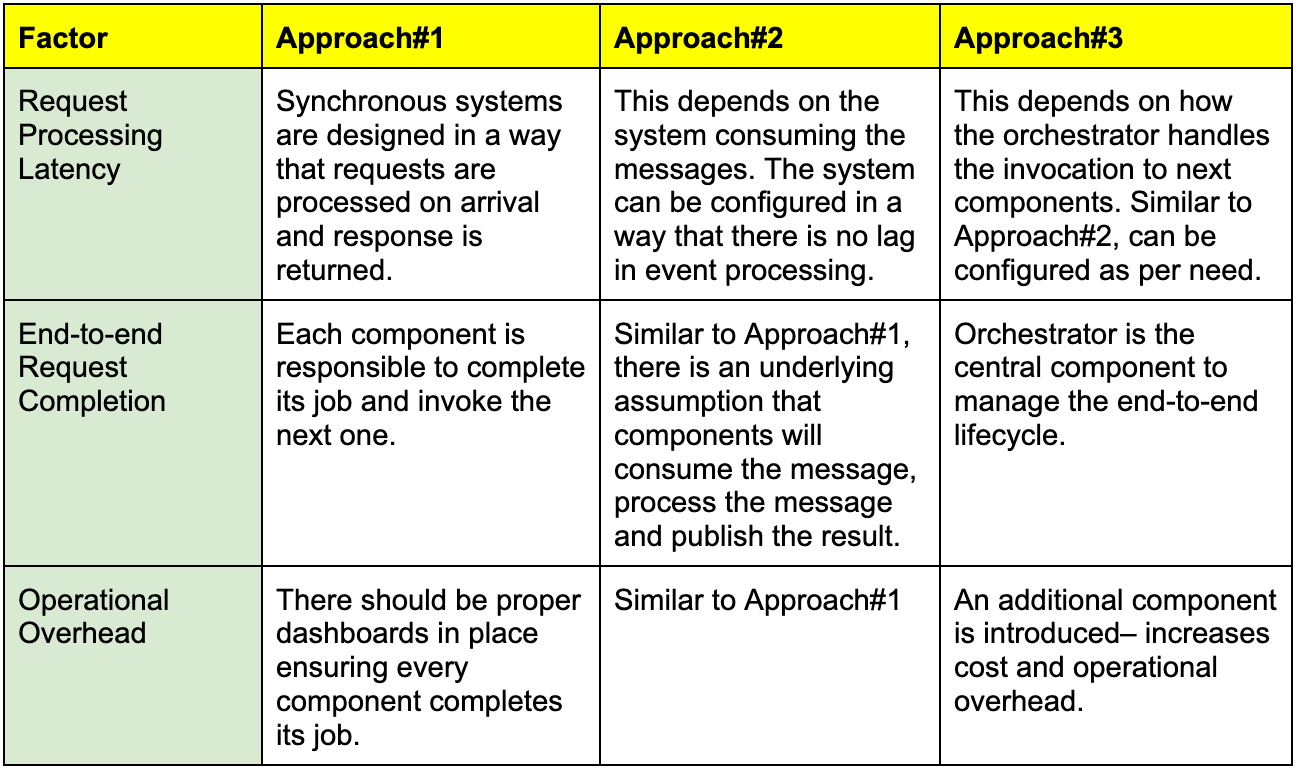

There are a few ways to coordinate the crawler components. Each option has its tradeoffs:

Approach #1: Synchronous communication

Each component exposes an API and calls the next component directly. If different components run inside the same service (microservice), they can call each other via local method calls.

Approach #2: Choreography

Each component publishes an event when it finishes its work. The next component consumes the event and continues the workflow. This is also known as event-driven architecture.

Approach #3: Orchestration

Add an orchestrator to manage the crawler’s lifecycle. The orchestrator triggers each step, tracks progress, and handles retries. Components can still communicate synchronously or asynchronously, depending on what fits.

…So which approach fits best here?

You might have heard the statement: “Everything is a tradeoff in system design.” This is very true: all approaches are best in one scenario but can be the worst in others.

Let’s do a trade-off analysis for the web crawler system:

For the crawler, Approach #3 (Orchestration) makes more sense. Here’s why:

End-to-end monitoring: You can track, retry, or debug each component.

Failure handling: If a component is unhealthy, the orchestrator can trigger a retry, pause, or reroute work.

Scheduling support: Orchestrator can schedule recrawls and also handle new URLs discovered during crawling.

Next, let’s combine these components and create a high-level diagram…

5. Web Crawler System Components

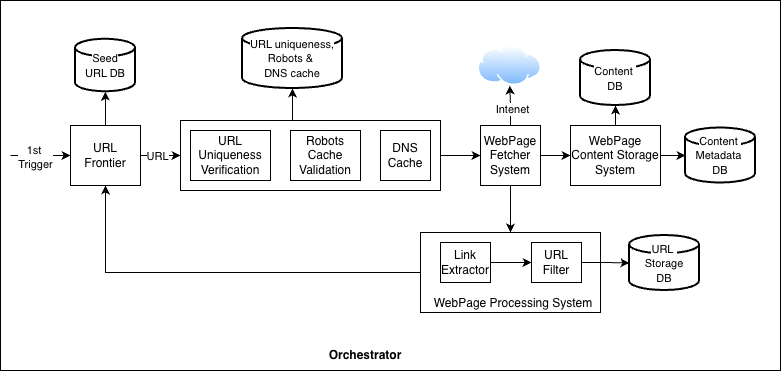

Figure 3 shows the end-to-end workflow.

The blocks in the diagram are logical components, not separate microservices. You can deploy them together or separately, depending on scale, cost, and operational needs.

Let’s summarize all the components and workflow:

URL Frontier

Starts with seed URLs and outputs the next URLs to crawl.

URL goes through certain validations, such as:

URL uniqueness (have we seen this URL before?)

Verification in robots.txt cache (is crawling allowed?)

Fetch IP address from DNS cache. This cache is continuously updated once the URL is fetched from the internet.

Webpage Fetcher System

Downloads the page content and stores it in the content database.

Some pages load content in multiple steps using JavaScript. For this, fetcher may need a headless browser to render the page and get the final content.

To save bandwidth, the system can cache shared resources, such as common JavaScript and CSS files, instead of downloading them repeatedly.

Webpage Processing System

Parses the downloaded page to extract new links. Then it filters these links using rules such as:

Blocklists

URL patterns

Region-based restrictions

Feedback loop

The extracted URLs are then sent back to the URL frontier, and the crawl cycle continues.

NOTE: A Domain Name System (DNS) handles mapping between domain names (such as google.com) to their IP addresses.

Web crawler’s job finishes as soon as the web page is downloaded and stored. Search engine then takes this content, builds indexes, and serves user queries.

Next, let’s explore the architecture of the search engine system…

This newsletter is inspired by Chapter 15 of the O’Reilly book “System Design on AWS”. Get a copy of the book right now.

Reminder: this is a teaser of the subscriber-only post, exclusive to my golden members.

When you upgrade, you’ll get:

Full access to system design case studies

FREE access to (coming) Design, Build, Scale newsletter series

FREE access to (coming) popular interview question breakdowns

And more!