Context Engineering 101: How ChatGPT Stays on Track

#109: What is Context Engineering

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

You’ve probably used an AI assistant like ChatGPT and gotten an answer that felt off.

You rewrote your question, added “think step by step,” and maybe gave a bit more detail. Sometimes it helped. Sometimes it didn’t…

That kind of trial and error is a form of prompt engineering: trying different ways of asking to get a better response. For simple tasks, it’s often enough. But once you ask the assistant to do something more complex, wording usually isn’t the main problem anymore.

More often, the issue is that the model is working with the wrong information.

Something important is missing, buried in the conversation, or mixed in with a lot of irrelevant text. The result can look like confusion: it loses the thread, makes shaky assumptions, or answers confidently without solid grounding.

This is where context engineering comes in.

Instead of asking, “How do I phrase this better?”, you ask, “What information should the model see right now?”

Andrej Karpathy, one of the founding members of OpenAI, describes it as:

“The delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.”

This newsletter looks at what that means in practice and how you can start doing it yourself (and how your favourite products like ChatGPT do it for the best user experience).

Onward.

Context is a system. Ours is the best. (Newsletter partner).

Most AI tools treat context like “a few files + a prompt.”

Augment Code’s Context Engine treats it like an engineering problem: retrieve the right dependencies, contracts, call paths, and history—then keep it fresh as your code changes.

Less drift. Less guessing. More ship.

I want to introduce Louis-François Bouchard as a guest author.

He focuses on making AI more accessible by helping people learn practical AI skills for the industry alongside 500k+ fellow learners.

What is Context?

Before getting into techniques or frameworks, it helps to be clear about what “context” actually means.

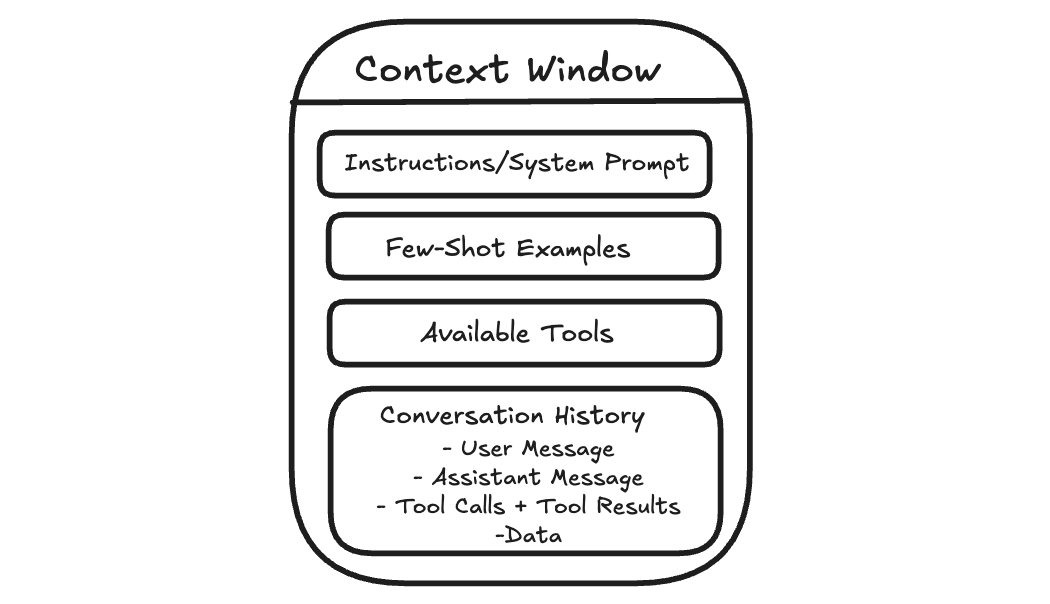

When you send a message to an AI assistant, it doesn’t just see your latest question. It sees the information included with your message, such as system instructions that guide its behavior, relevant parts of the conversation so far, any examples you provide, and sometimes documents or tool outputs.

All of that together is the context.

This matters because the model lacks long-term memory as humans do. It cannot recall past conversations unless that information is included again. Each response is generated solely from the current context.

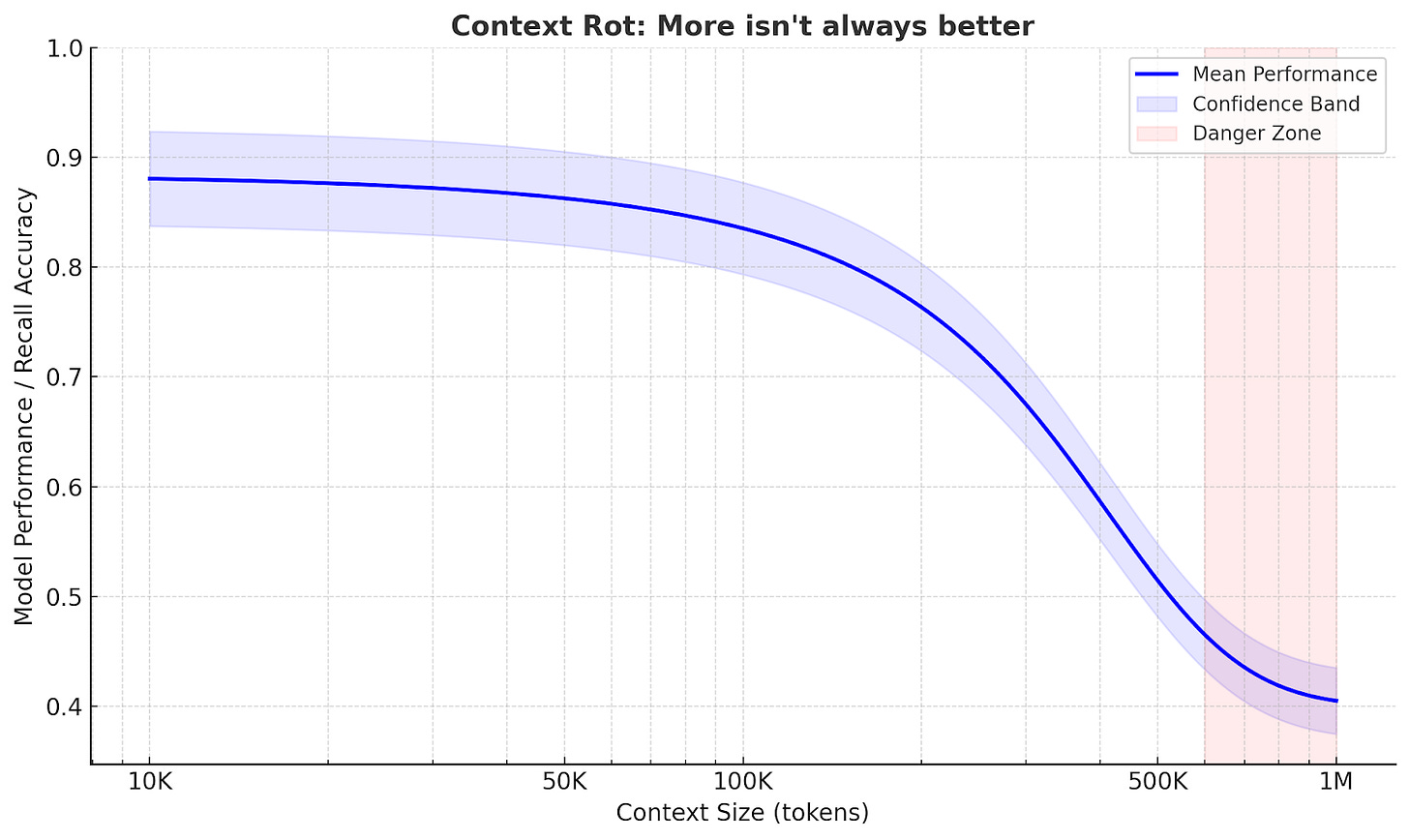

The model can pay attention to only a limited amount of text at once. This limit is often called the context window. Dumping more into that space often makes answers worse, not better.

Context engineering is about managing that working space.

The goal is not to give the model as much information as possible, but to give it the right information at the moment it needs to respond.

Why does this matter for agents?

This becomes more important when the AI is doing more than answering a single question.

A simple chatbot takes your question, replies, and stops. But more advanced AI systems, often called agents, work on tasks that unfold over many steps. They might search for information, read results, summarize what matters, and then decide what to do next.

Each step generates new information that is added to what the model sees next, such as search results, summaries, and intermediate notes. Over time, the context grows, and much of it becomes no longer relevant to the current step. This is called context rot, where useful information gets buried under outdated details.

Agents often work well on focused tasks.

But when a task is broad and requires many steps, the quality can vary. As the context gets heavier, important details from earlier can get lost.

The Anatomy of Context

Understanding what causes context rot is the first step.

The next is knowing exactly what goes into the context window so you can control it.

When an AI generates a response, it is not just reacting to your last message. It is responding to a structured bundle of inputs. Each part plays a different role, but they all compete for the same limited space.

System Prompt and User Prompt

The system prompt determines the model's overall behavior.

It describes how the assistant should act, the rules it should follow, and the kinds of responses expected.

Most of the time, you do not see the system prompt directly. It’s defined by the product or application you are using. This is why two assistants built on the same underlying model can behave very differently.

For example, ChatGPT tends to answer politely, refuse certain requests, and format responses in predictable ways, even if you never explicitly asked it to do so.

The user prompt is your message.

This includes your current question and, in a chat setting, earlier messages that are still included.

Both are sent to the model together. The system prompt guides behavior, and the user prompt describes what to do right now.

If you are building an AI feature and you control the system prompt, the hard part is balance. If the instructions are too strict, the assistant can become brittle when something unexpected occurs. If they are too vague, responses become inconsistent.

A practical approach is to start minimal, test with real use cases, and add rules only when you see specific failures.

Examples

Sometimes the clearest way to guide an AI is to show it what you want.

Instead of writing a long list of rules, you can include one or two example inputs and the exact outputs you expect. This is often called few-shot prompting.

You have probably done this in ChatGPT without realizing it. If you say, “Format it like this,” and paste a sample answer, the model will usually follow the pattern.

Examples work because they remove ambiguity. They show tone, structure, and level of detail in a way that instructions often cannot.

The tradeoff is space. Examples take up room in the context window, so they need to earn their spot. A few well-chosen examples are usually better than a long list.

Message History

In a chat, the model can respond to follow-up questions because earlier messages remain in context.

For example, if you ask ChatGPT, “What is the capital of France?” and then ask, “What is the population?”, it can usually infer you still mean the capital you just discussed.

This works because the conversation so far acts like shared scratch paper. The model does not truly remember the earlier exchange. It is simply reading it again as part of the input.

The problem is that the message history grows over time. As more turns accumulate, older messages take up space even when they are no longer relevant. That can make the model less focused. It may repeat itself, follow outdated assumptions, or miss a detail that matters now.

Managing message history usually means keeping what is still relevant, summarizing what is settled, and letting the rest drop out of the active context.

Tools

On its own, an LLM can only generate text. Tools let it do more than that.

Tools allow an agent to search the web, read documents, run code, query databases, or interact with external systems. When a tool is used, the result is usually fed back into the context so the model can use it in the next step.

You have seen this in ChatGPT when it searches the web or analyzes a file you uploaded. The output becomes part of what the model sees before it responds.

Tools are powerful, but every tool call adds more text that competes for attention. If a tool returns too much information or in an unclear format, it can overwhelm the model rather than help it.

Good tool design keeps results focused and predictable. Clear names, narrow responsibilities, and concise outputs make it easier for the model to use tools effectively.

Data

Beyond messages and tools, agents often work with external data.

This can be a document you upload, an article you paste into the chat, or files the system can access. When that information is included, it becomes part of the context.

Large documents do not always behave the way you expect. The model may focus on the wrong section or miss details. This is often a context management problem, not carelessness.

Managing documents usually means breaking them into smaller pieces, pulling in what is relevant to the current step, and leaving the rest out of the active context until needed.

Stop stuffing the context window. (Newsletter partner).

The trick isn’t more context—it’s the right context at the right step.

Augment’s Context Engine curates and composes context for professional engineers working in real, messy systems—so your agent can reason about architecture, not just autocomplete a diff.

Context Retrieval Strategies

System instructions, examples, tools, and message history are the context in which you can write directly.

But often the most important information is not known in advance. It has to be retrieved during the task.

For example, if you ask ChatGPT a question about a PDF you uploaded, it needs to find the relevant section. If you ask it to search the web, it has to decide what to search for and which results matter.

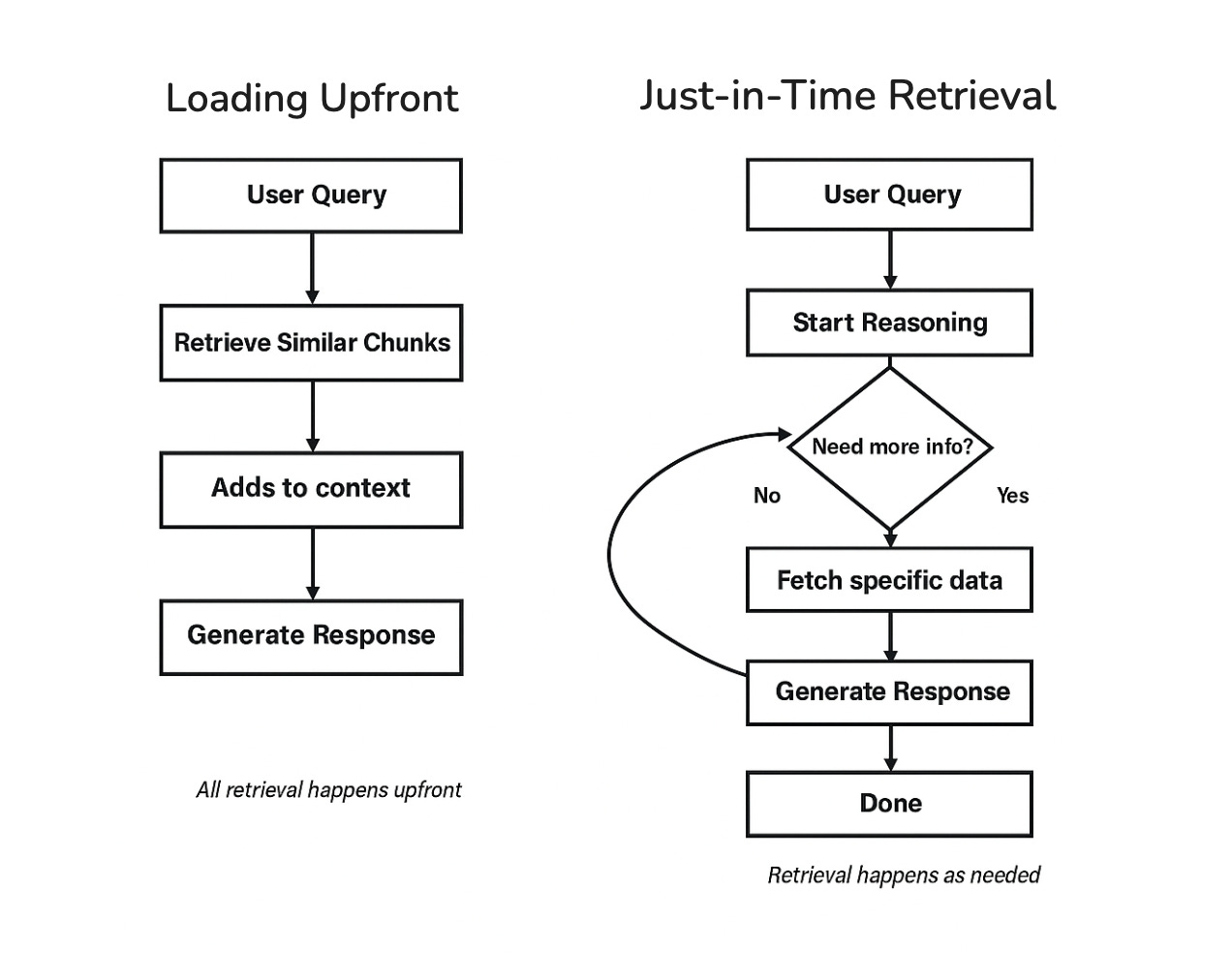

How an agent retrieves and injects information is a major part of context engineering. There are two main approaches: loading everything upfront, or retrieving as you go.

Loading Upfront

The simplest approach is to retrieve relevant information before the model starts responding, then include it in the context all at once.

This is what happens when ChatGPT searches the web and then writes an answer using the results it just found. The model is not answering from memory. It is answering based on the information that was retrieved and added to its context.

This pattern is commonly called retrieval augmented generation (RAG).

Loading upfront works well when the question is clear, and the agent can predict what information will be useful. The downside is that the agent makes an early retrieval decision and may stick with it.

If something important is missing or the task changes direction, it can be harder to correct course.

Just-in-Time Retrieval

Another approach is to retrieve information as the task unfolds.

Instead of loading everything at the start, the agent takes a step, looks at what it has learned so far, and retrieves more information only when needed. You can sometimes see this in ChatGPT when it searches, reads, refines the query, and searches again during longer tasks.

This keeps the context cleaner because only the information actually needed gets pulled in. The tradeoff is that it takes more steps and requires the agent to decide when to retrieve and when to stop.

A useful pattern within just-in-time retrieval is to start broad and then drill down. This specification is called Progressive Disclosure.

Rather than loading full documents immediately, the agent may start with short snippets or summaries, identify what looks relevant, and pull in more detail only then.

This is how humans tackle research, too.

You do not read every article in a database. You scan titles, read abstracts of promising ones, and dive deep only into the sources that matter.

Hybrid Strategy

Fortunately, you don’t have to pick one or the other.

Many agents combine both approaches. They load a small amount of baseline information upfront, then retrieve more as needed.

You can see this in tools like ChatGPT. Some instructions and conversation history are already present, and additional information, such as search results or document excerpts, is pulled in based on what you ask.

For simpler use cases, loading upfront is often enough. As tasks get more complex and span multiple steps, retrieving as you go becomes more important.

The right choice depends on how predictable your agent’s information needs are.

Your codebase is bigger than your IDE. (Newsletter partner).

Modern systems sprawl across repos, services, configs, and runbooks.

Augment’s Context Engine is built to pull relevant context across that reality—so AI answers don’t collapse the moment you leave the file you have open.

Techniques for Long-Horizon Tasks

Retrieval helps an agent pull in the right information.

But some tasks create a different problem. They run long enough that the agent produces more text than can fit in the context window.

You may have seen this in ChatGPT during long conversations or research tasks. Early responses are clear, but after many steps, the answers can drift or repeat themselves, especially when you send very long instructions, like asking for help with entire code bases. Over a long task, the agent can encounter far more information than it can keep in working memory at once.

Larger context windows are not a complete solution. They can be slower and more expensive, and they still accumulate irrelevant information over time. A better approach is to actively manage what stays in context and preserve the important parts as the task grows.

Three techniques help with this:

compressing the context when it gets full,

keeping external notes,

splitting work across multiple agents.

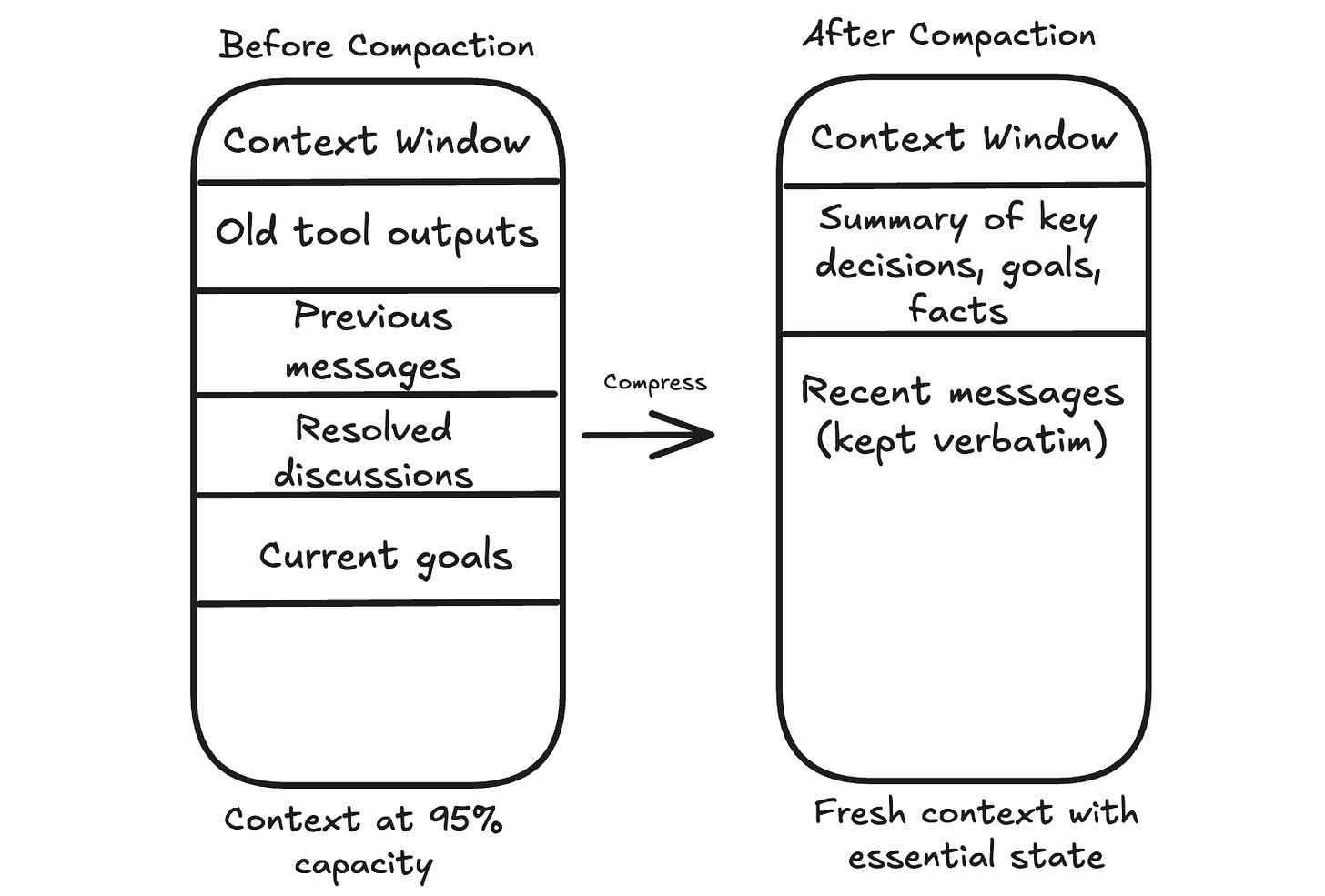

1. Compaction

When the context approaches its limit, one option is to compress what’s there.

The agent summarizes the conversation so far, keeping the essential information and discarding the rest. This compressed summary becomes the new starting point, and the conversation continues from there.

You may have noticed something like this in long ChatGPT conversations. After many messages, earlier details can fade. This often happens because older parts of the conversation are shortened or dropped to make room for new input.

The hard part is deciding what to keep.

The goal, key constraints, open questions, and decisions that affect future steps should stay. Raw tool outputs that have already been used can usually go. Repeated back and forth that does not change the plan can go too.

There is always a risk of losing something that matters later. A common safeguard is to store important details outside the context before discarding them, so the agent can retrieve them if needed.

2. Structured Note Taking

Compaction occurs when you’re running out of space. Structured note-taking happens continuously.

As the agent works, it keeps a small set of notes outside the context window. These notes capture stable information, such as the goal, constraints, decisions made so far, and a short list of what remains.

You can see a user-level version of this idea in features like ChatGPT’s memory. If you tell it to remember something, that information can persist beyond a single conversation and be brought back when relevant.

This works well for tasks with checkpoints or tasks that span multiple sessions.

A coding agent might keep a checklist of completed steps. A support assistant might store user preferences so that it does not have to ask the same questions again.

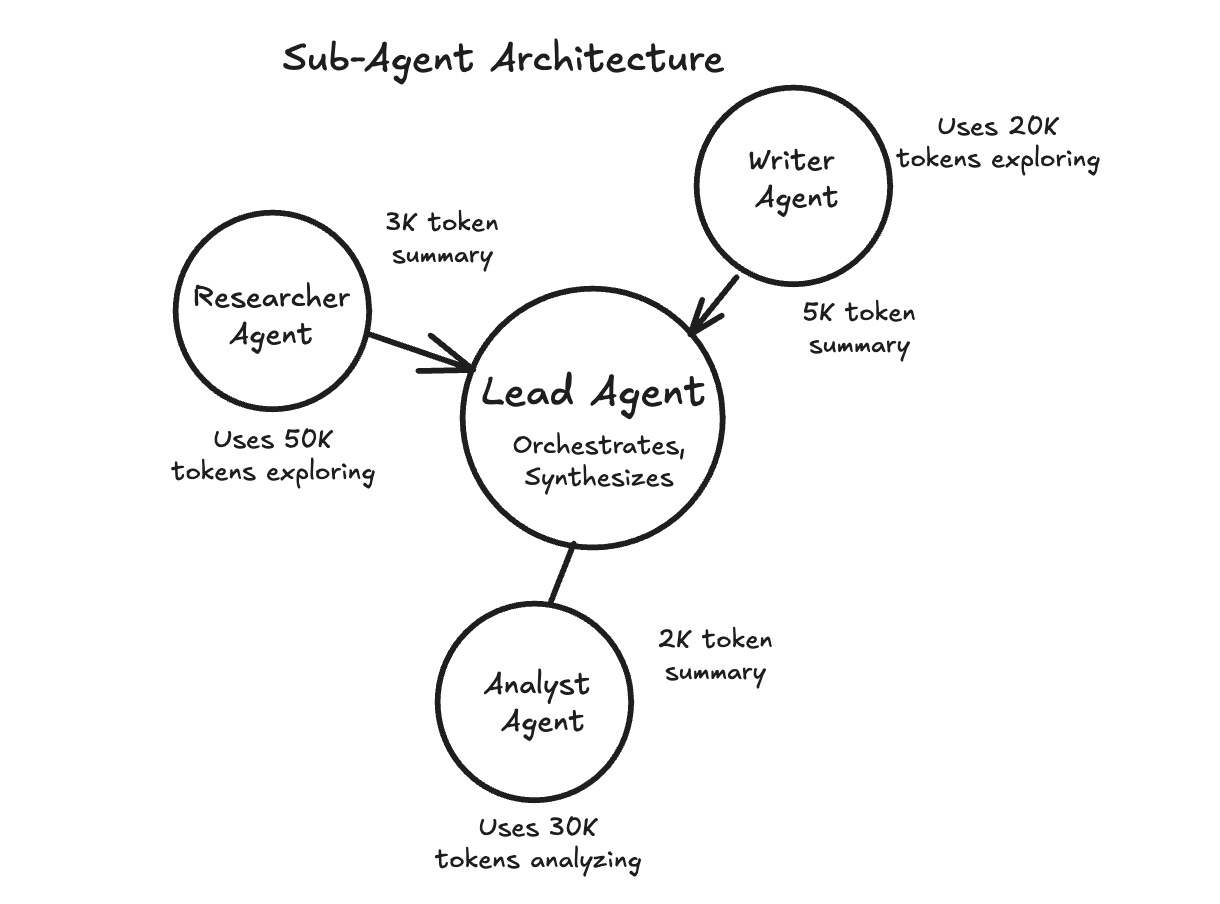

3. Sub-Agent Architectures

Sometimes the best approach is to break a large task into pieces and assign each piece to a separate agent with its own context window.

In many research-style agent designs, a main agent coordinates the overall task, while sub-agents handle focused subtasks. A sub-agent explores one area in depth, then returns a short summary. The main agent keeps the summary and moves on without carrying all the raw details forward.

You can think of research features in tools like ChatGPT as an example of the kind of workflow where this pattern is useful.

This works well when subtasks can run independently or require deep exploration.

The tradeoff is complexity. Coordinating multiple agents is harder than managing a single one, so it is usually best to start with simpler techniques and add sub-agents when a single agent becomes overwhelmed.

Choosing the Right Technique

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution. The right approach depends on your “agent and your use case”. These rules of thumb can help:

Compaction works best for long, continuous conversations where context gradually accumulates.

Structured notes work best for tasks with natural checkpoints or when information needs to persist across sessions.

Sub-agents work best when subtasks can run in parallel or require deep, independent exploration.

These techniques can be combined. Start with the simplest approach and add complexity as needed.

Putting It All Together

Context engineering is not a single technique.

It’s an approach to designing AI systems. At each step, you decide what goes into the model’s context, what stays out, and what gets compressed.

The components we covered work together.

System prompts and examples shape behavior. Message history maintains continuity. Tools let the agent take actions. Data gives it information to work with. Retrieval strategies determine how and when that information gets loaded. For long-running tasks, compaction, external notes, and sub-agents help manage context that would otherwise overflow.

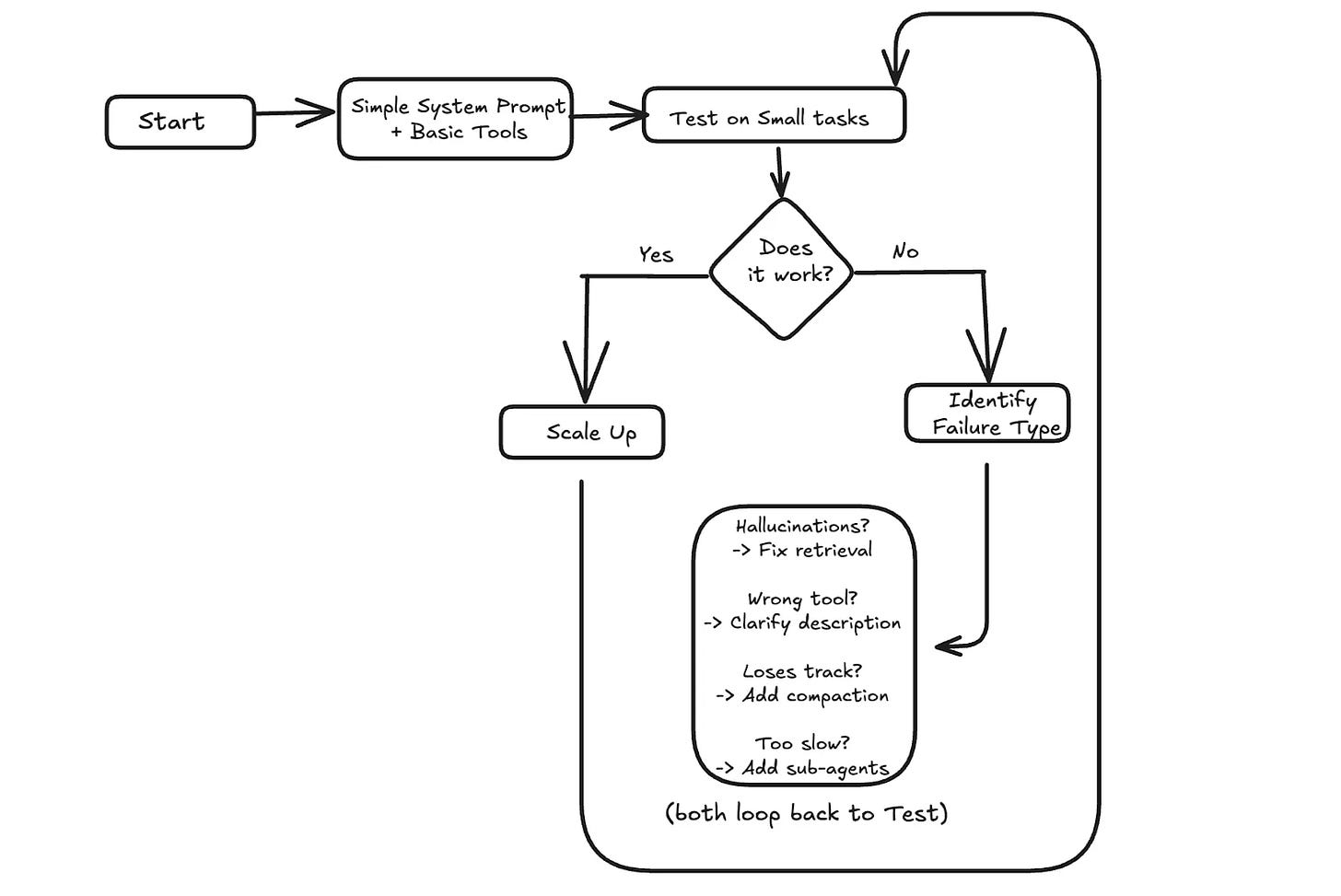

When something goes wrong, context is often the place to look. If the agent hallucinates, it might need better retrieval to ground its answers. If it picks the wrong tool, the tool descriptions might be unclear. If it loses track after many turns, the message history might need summarization.

A practical approach is to start simple.

Test with small tasks first. If it works, scale up. If it fails, identify what went wrong and address the specific issue.

Context engineering, operationalized. (Newsletter partner).

If you like the idea of context engineering, you’ll like what Augment does in practice:

A dedicated Context Engine that continuously grounds your AI in the code, relationships, and constraints that actually matter—without you playing prompt Tetris.

I launched Design, Build, Scale (newsletter series exclusive to PAID subscribers).

When you upgrade, you’ll get:

High-level architecture of real-world systems.

Deep dive into how popular real-world systems actually work.

How real-world systems handle scale, reliability, and performance.

10x the results you currently get with 1/10th of your time, energy, and effort.

👉 CLICK HERE TO ACCESS DESIGN, BUILD, SCALE!

Want to reach 200K+ tech professionals at scale? 📰

If your company wants to reach 200K+ tech professionals, advertise with me.

Thank you for supporting this newsletter.

You are now 200,001+ readers strong, very close to 201k. Let’s try to get 201k readers by 21 December. Consider sharing this post with your friends and get rewards.

Y’all are the best.

Playbook

Augment legacy plan user is here . I loved augment.