System Design Interview: Design WhatsApp

#106: System Design Interview - Part 1

Share this post & I’ll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Block diagrams created using Eraser.

Designing a real-time chat application like WhatsApp is one of the most common system design interview questions.

In a short period, you need to show that you understand not just the happy path, but also all the things that can go wrong when messages fly between disconnected users on mobile networks.

WhatsApp handles over 100 billion messages daily for 2+ billion users.

We’ll build this from scratch, starting with a simple version that works for a few thousand users, then scale it up to handle billions of users sending messages across unreliable mobile networks.

This is a practical guide:

We won’t hand-wave away the hard parts or pretend everything works. Instead, we’ll build something functional, identify where it breaks, and fix it properly.

What we’ll cover in Part 1:

Requirements and capacity estimation

Core architecture and data models

Why WebSockets beat other protocols for real-time messaging

Service discovery and presence management

Handling online and offline message delivery

Multi-device synchronization

Media file uploads without killing your servers

By the end, you’ll understand not just what to build, but why each decision is made and what breaks when you get it wrong.

Onward.

🔥 Ditch the vibes, get the context (sponsor)

Augment Code’s powerful AI coding agent meets professional software developers exactly where they are, delivering production-grade features and deep context into even the gnarliest codebases.

With Augment Code, you can:

Keep using VS Code, JetBrains, Android Studio, or even Vim

Index and navigate millions of lines of code

Get instant answers about any part of your codebase

Build with the AI agent that gets you, your team, and your code

👉 Ditch the Vibes and Get the Context You Need to Engineer What’s Next

I want to introduce Hayk Simonyan as a guest author.

He’s a senior software engineer specializing in helping developers break through their career plateaus and secure senior roles.

If you want to master the essential system design skills and land senior developer roles, I highly recommend checking out Hayk’s YouTube channel.

His approach focuses on what top employers actually care about: system design expertise, advanced project experience, and elite-level interview performance.

Requirements: What Are We Actually Building?

Starting simple… we’re designing a real-time messaging app that lets people send text messages and media to each other. But let’s get specific about what “real-time” actually means here.

Core requirements:

Users can send and receive text messages in 1:1 chats

Group chats with up to 100 participants (we’ll see why this number matters later)

Messages delivered while users are offline get queued up for 30 days

Media attachments (images, videos, audio clips)

Message status tracking (sent, delivered, read)

Online/offline status with “last seen”

Non-functional requirements:

Low latency delivery (under 500ms when users are online)

Guaranteed message delivery (messages can’t just disappear)

Handle billions of users with high throughput

Don’t store messages on servers longer than necessary

Stay resilient when individual components fail

The tricky bit most people miss is the offline requirement.

It’s easy to design for everyone to be online. But real life doesn’t work that way…

Back-of-the-Envelope: Understanding the Scale

Let’s run the numbers so we don't build something that collapses under real load.

User metrics:

1 billion registered users

500 million daily active users

50 million concurrent connections during peak hours

Average 10-20 messages per user daily

Message estimations:

Daily messages: 500M users × 20 messages = 10 billion messages/day

That’s roughly 115,000 messages per second on average.

But during peak hours, we need to multiply that by 3-5x. So we’re looking at 350,000-500,000 messages per second.

Storage calculation:

Each message with metadata averages about 1KB (text content, sender/receiver IDs, timestamp, status flags, etc.)

Daily storage: 1KB × 10B messages = 10 TB/day

Annual storage: 3.6 PB/year

But here’s the thing:

Most messages get delivered and cleared from the server within seconds. We’re not storing everything forever. Users download messages to their devices, and we clean them up on the server.

Factor in the 30-day retention for undelivered messages and 10% of users keeping history on servers. And suddenly we’re looking at 400-500 TB of active storage instead of petabytes.

Bandwidth:

50M concurrent connections at peak.

If each connection averages 10KB/s for active messaging, that’s 500 GB/s of bandwidth. This is why WhatsApp was famous for running on minimal infrastructure.

They are very efficient in not sending unnecessary data.

High-Level System Design

Let’s build this in stages, starting simple and adding complexity only when we need it:

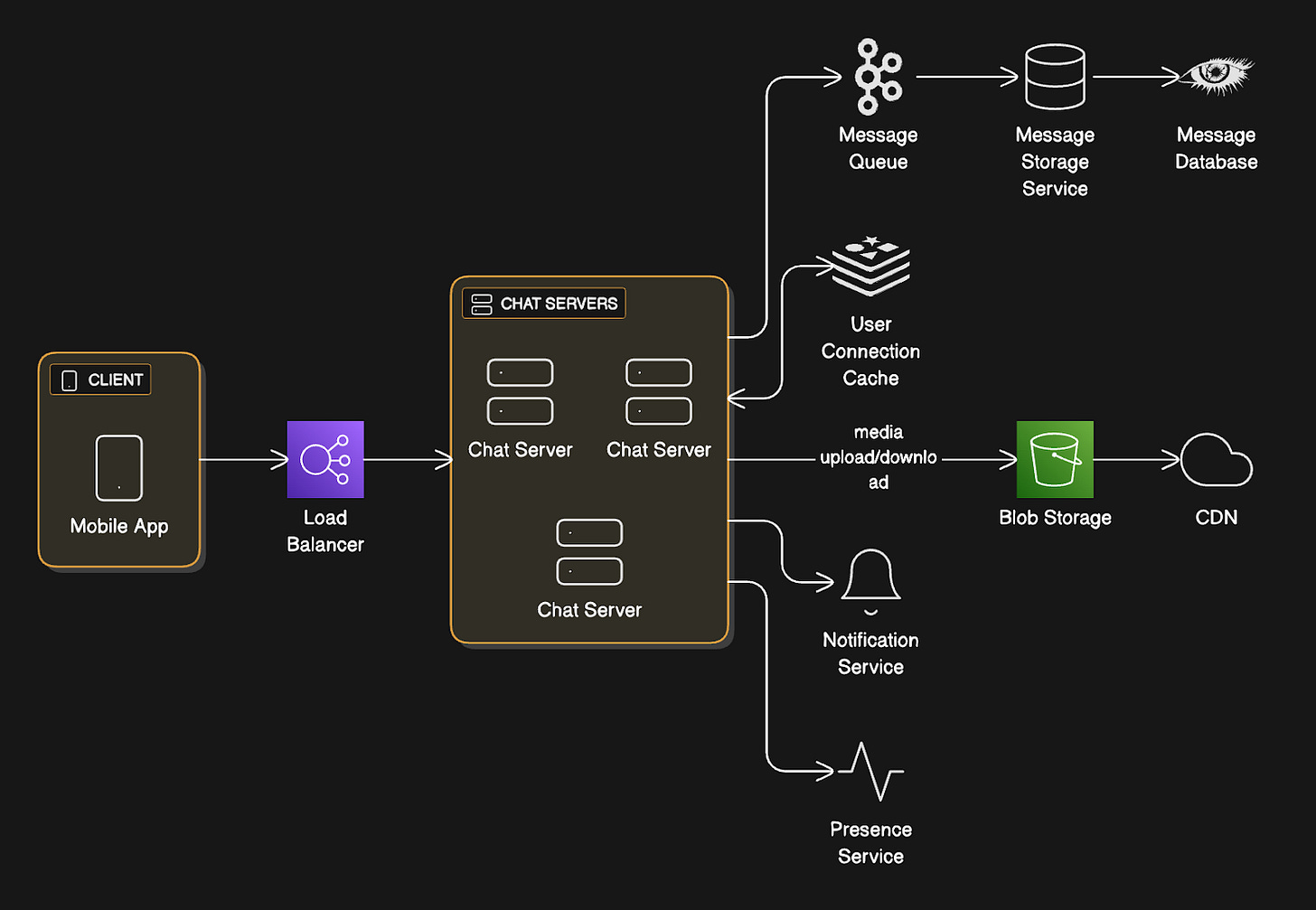

The Basic Components

Mobile App (Client)

The user’s phone. It maintains a persistent connection to our backend, handles the UI, manages local message storage, and retries failed operations.

Load Balancer

This sits in front of our chat servers and distributes incoming connections across multiple servers.

Think of it as a traffic cop routing cars to different lanes. It routes incoming WebSocket connections to chat servers and uses sticky sessions (meaning once you connect to Server A, you stay on Server A). Simply put, users don’t bounce between servers mid-conversation.

It also monitors server health and stops sending traffic to dead servers.

Chat Servers

Chat servers maintain WebSocket connections to clients (a persistent two-way communication channel that stays open), route messages between users, track who’s online, and handle message persistence.

Each server can handle hundreds of thousands of simultaneous connections.

Message Queue

This decouples message writing from delivery.

When a chat server receives a message, it immediately acknowledges receipt to the sender, then asynchronously pushes it to the queue for storage and delivery.

We can use tools like Kafka or RabbitMQ that work well here.

Message Storage Service

Consumes from the queue and writes messages to the database.

It also handles querying message history and managing retention policies (such as deleting old messages after 30 days).

Message Database

Persistent storage for messages.

NoSQL works well here (Cassandra, DynamoDB) because we need high write throughput and our query patterns are straightforward (fetch messages by user/conversation/timestamp).

We’re writing billions of messages per day, so we need something that can handle massive write volume without slowing down.

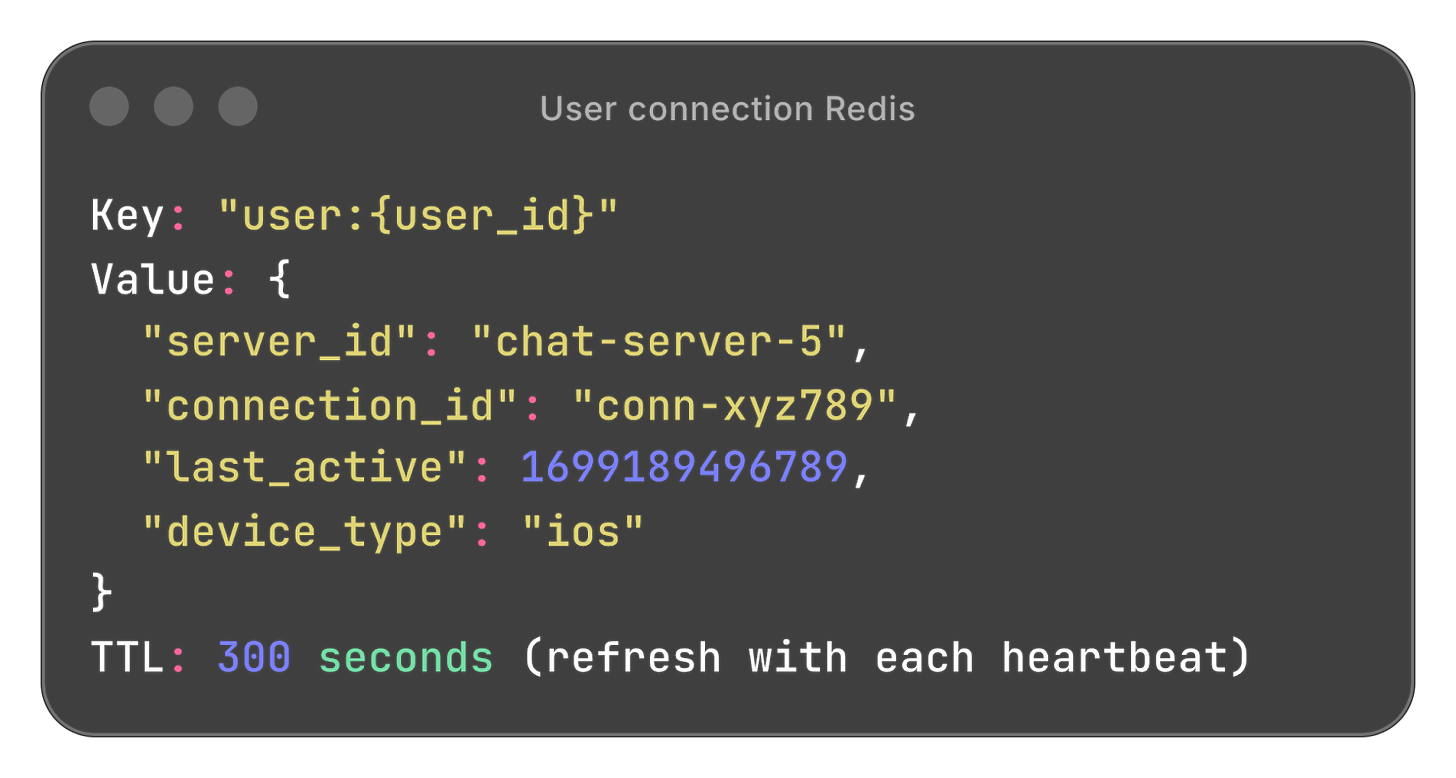

User Connection Cache

In-memory store (Redis) tracks which users are online, which chat server they’re connected to, and their last activity timestamp.

This makes routing decisions fast. Checking Redis takes microseconds, whereas querying a database takes milliseconds. At scale, that difference matters.

Blob Storage + CDN

Blob storage (e.g., AWS S3 or Google Cloud Storage) stores media files; it holds the actual files.

CDN (Content Delivery Network) caches popular files at edge locations worldwide so downloads are fast regardless of where users are. It offers direct upload/download paths so chat servers don’t become bottlenecks for large file transfers.

Notification Service

Handles push notifications for offline users through APNs (Apple Push Notification Service for iOS) and FCM (Firebase Cloud Messaging for Android).

When someone messages you while you’re offline, this makes your phone buzz.

Presence Service

Dedicated service for managing online/offline status. Receives heartbeats from users, updates Redis, and publishes presence changes to interested subscribers.

The WebSocket Decision

Most messaging systems use WebSockets.

Let’s understand why by looking at what doesn’t work:

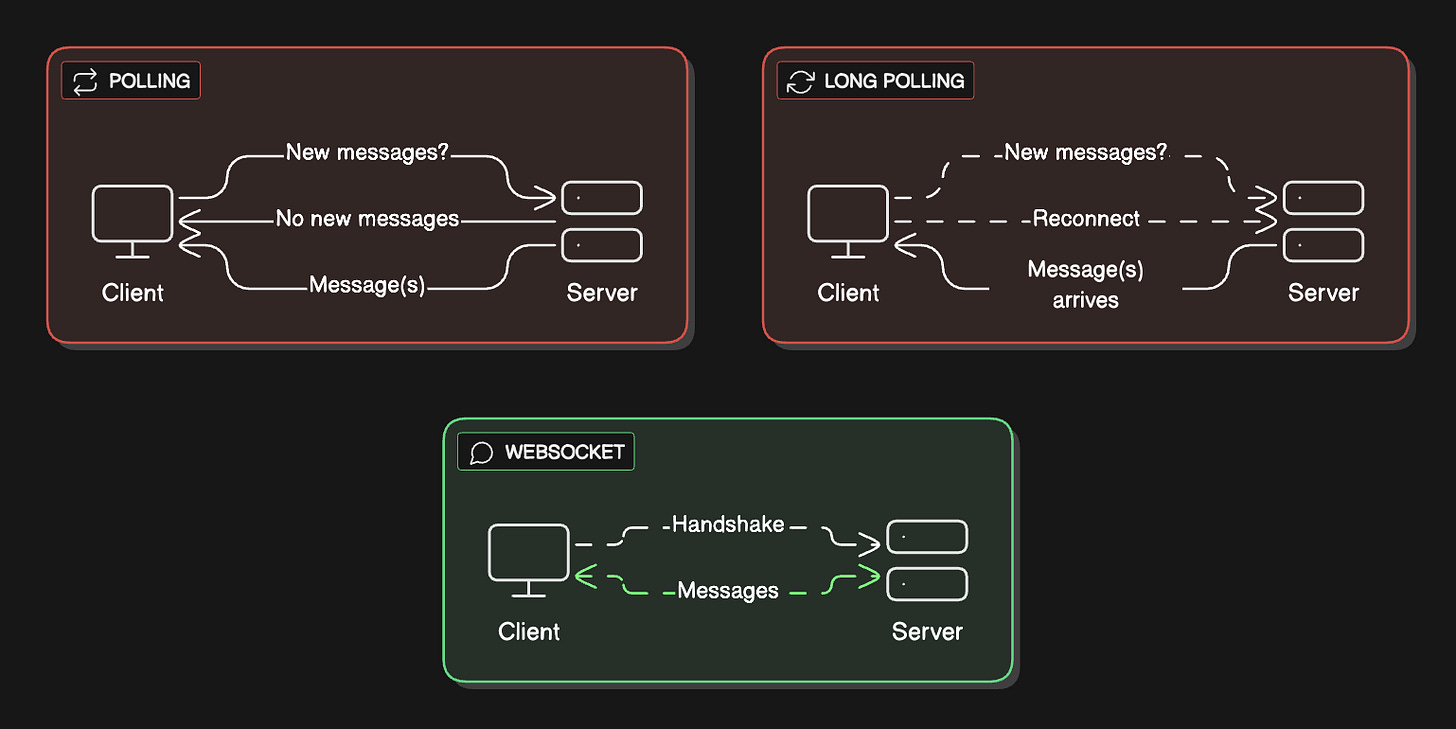

Polling

The client asks, “Any new messages?” every few seconds.

This wastes bandwidth and adds latency.

If you’re checking every 2 seconds and a message arrives right after you check, you wait 2 seconds to see it. Multiply that by millions of users constantly asking for updates even when there’s nothing new, and you’re burning resources for no reason.

Long polling

Client opens a request, server holds it open until there’s a message or a timeout.

Long polling is better than regular polling.

But it’s still problematic:

You’re constantly opening and closing connections. Each message requires a full HTTP handshake (the back-and-forth to establish a connection).

At scale, this overhead kills you. Your servers spend more time managing connection lifecycles than actually delivering messages. Plus, idle HTTP connections still consume server resources (memory for connection state, thread pool slots) without the efficiency benefits of WebSockets.

WebSockets (WHAT WE USE)

One persistent bidirectional connection that stays open. Both the client and the server can push data at any time. Minimal overhead once established.

Why we chose WebSocket:

The connection remains open throughout the session. When User A sends a message to User B, it flows through A’s WebSocket connection to the server, which pushes it through B’s WebSocket connection instantly.

No polling and no repeated handshakes. Just data flowing both ways. The connection overhead happens only once when you open the app; everything after that is just message content.

WebSocket Tradeoffs:

It requires special load balancers that support them (Layer 4 load balancing instead of Layer 7).

They also use more memory per connection on the server since you’re keeping connections open.

But for real-time messaging, the latency and bandwidth benefits make it worthwhile.

Handling Idle WebSocket Connections:

What happens when a user opens WhatsApp but doesn’t send any messages for hours?

The connection stays open but idle!

We handle this with heartbeats: Client sends a lightweight ping every 30 seconds. Server responds with Pong.

If the server doesn’t receive a heartbeat for 60 seconds, it assumes the connection died (network issue, app backgrounded) and closes it. This prevents the accumulation of zombie connections that waste server resources.

Idle connections still consume memory (connection state, socket buffers), but the cost is minimal compared to the benefit of instant message delivery when the user sends something.

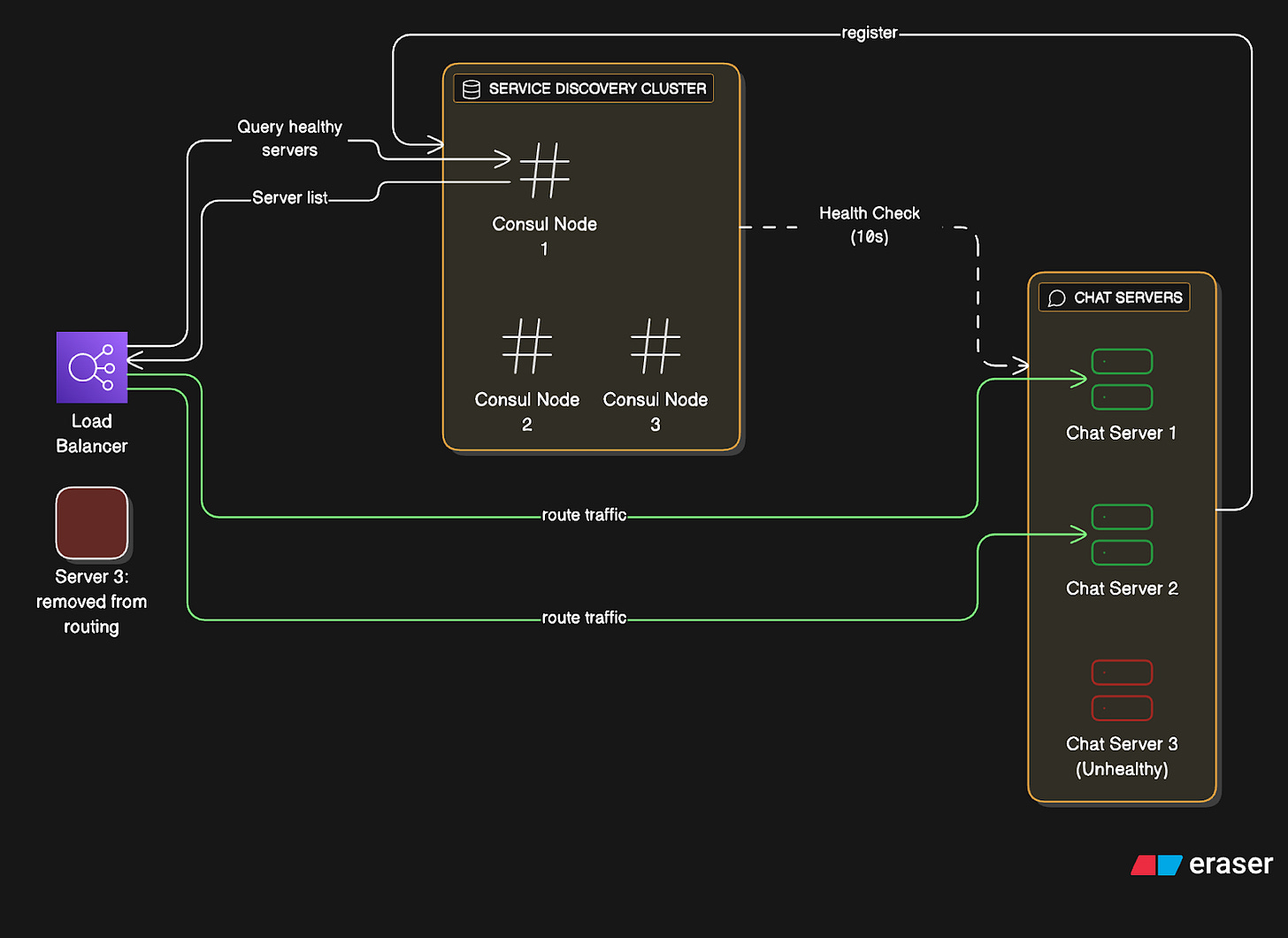

Identifying Servers That Don’t Stand Still

In production, chat servers come and go… they crash, get deployed, scale up and down. So how does the system keep track of what’s available?

The Problem:

Your load balancer needs to know which chat servers are healthy.

Chat servers need to know which other services are available (Message Storage Service instances, Redis cluster nodes). Hardcoding IPs doesn’t work when instances are ephemeral.

Solution: Service Registry Pattern

We use a service registry such as Consul or AWS Cloud Map.

Here’s how it works:

Registration:

When the Chat Server starts:

Server boots up on IP

10.0.1.45:8080Registers itself with Consul:

Service name:

“chat-server”Instance ID:

“chat-server-abc123”Health check endpoint:

“/health”Metadata:

{region: “us-east”, capacity: 100000}

3. Sends a heartbeat every 10 seconds

4. If the heartbeat stops, Consul marks it unhealthy after 30 seconds

Discovery:

When the Load Balancer needs available servers:

Query Consul: “Give me all healthy chat-server instances”

Consul returns list:

[10.0.1.45:8080, 10.0.1.67:8080, ...]Load balancer updates the routing table

Watches for changes (Consul notifies on updates)

Why we chose this:

Services discover each other dynamically.

Deploy new servers; they auto-register.

Kill a server, and it’s automatically removed.

No manual configuration updates.

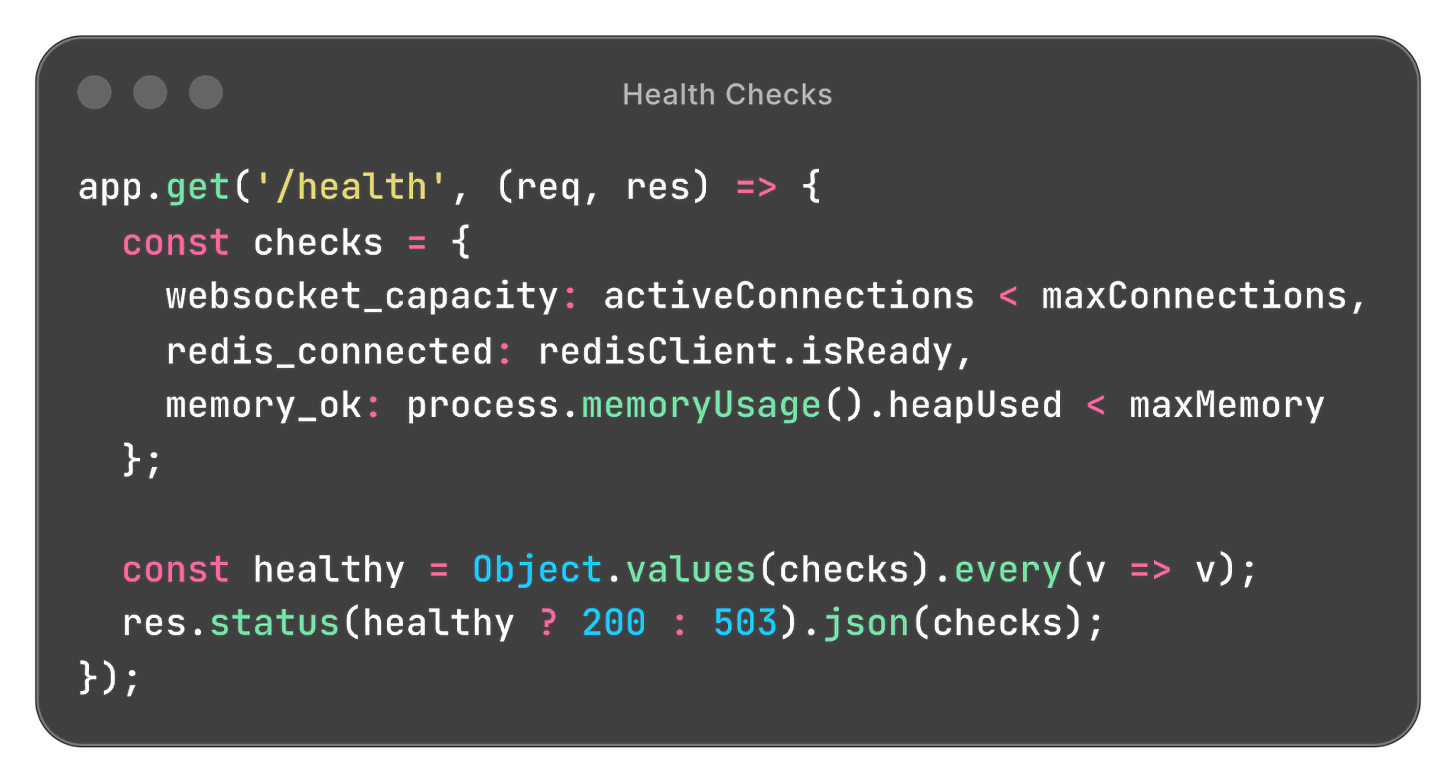

Health Checks:

Consul hits this endpoint every 10 seconds.

If the instance fails three times in a row, it is marked unhealthy.

Tradeoffs:

Service discovery adds another system to maintain (Consul cluster needs to be highly available).

But the alternative is manual instance management, which doesn’t scale and causes outages when you forget to update configurations.

Data Models

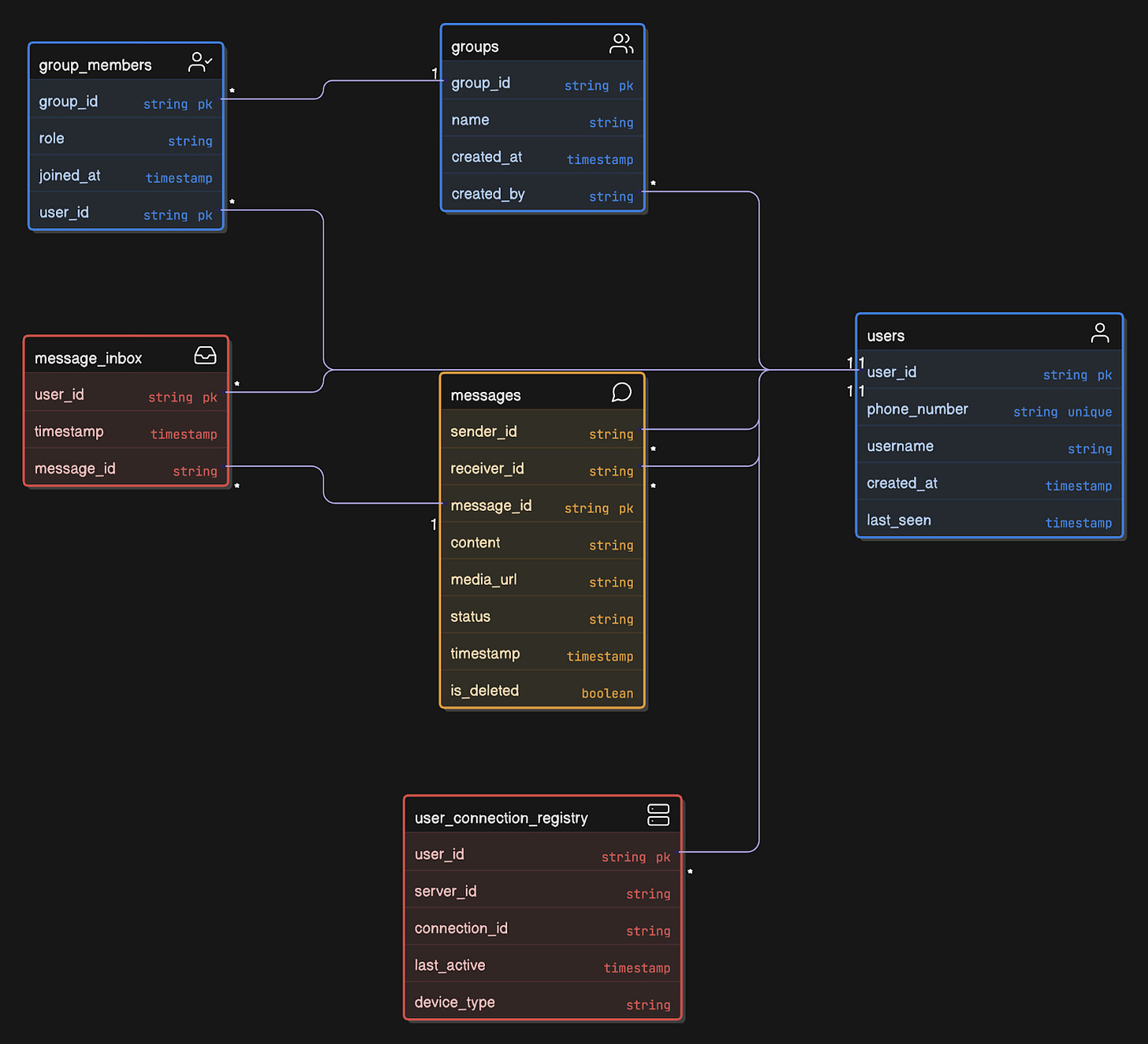

Let’s design tables that actually support our use cases:

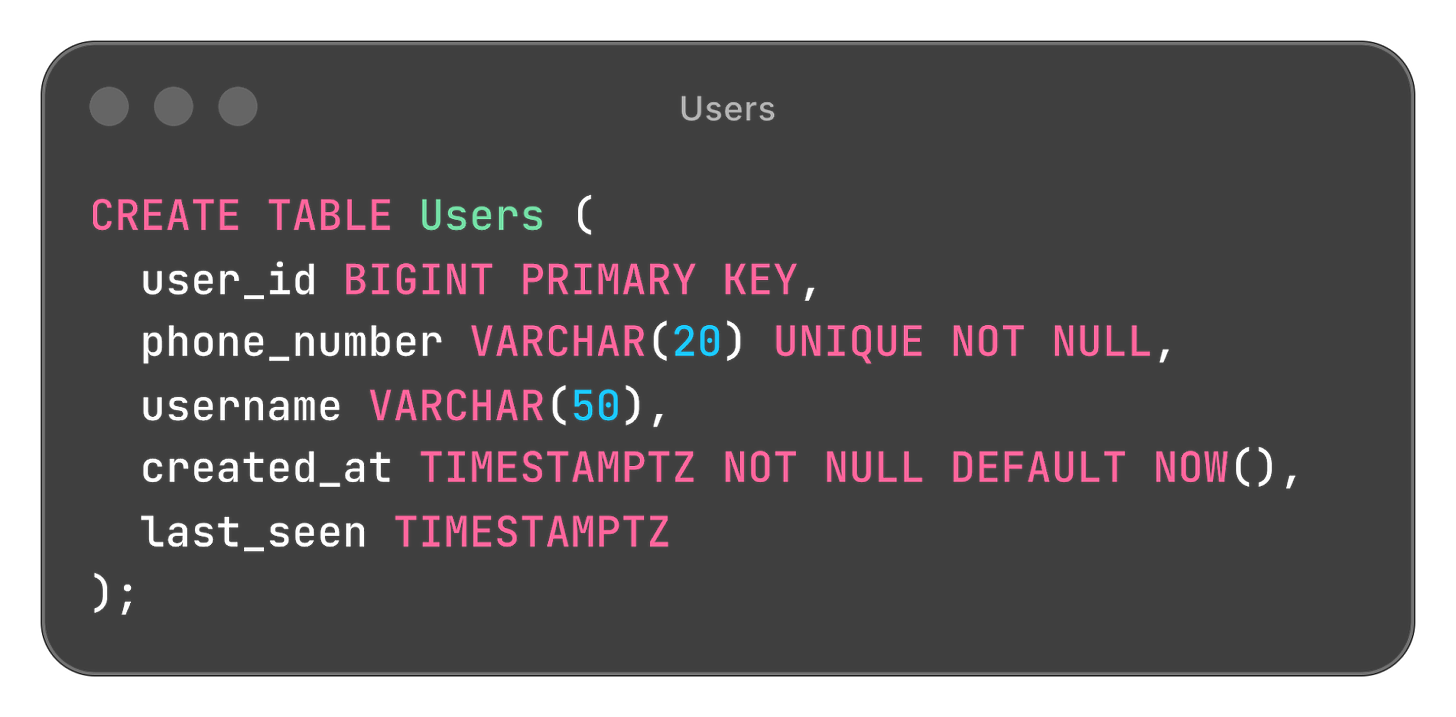

Users Table (SQL - PostgreSQL works)

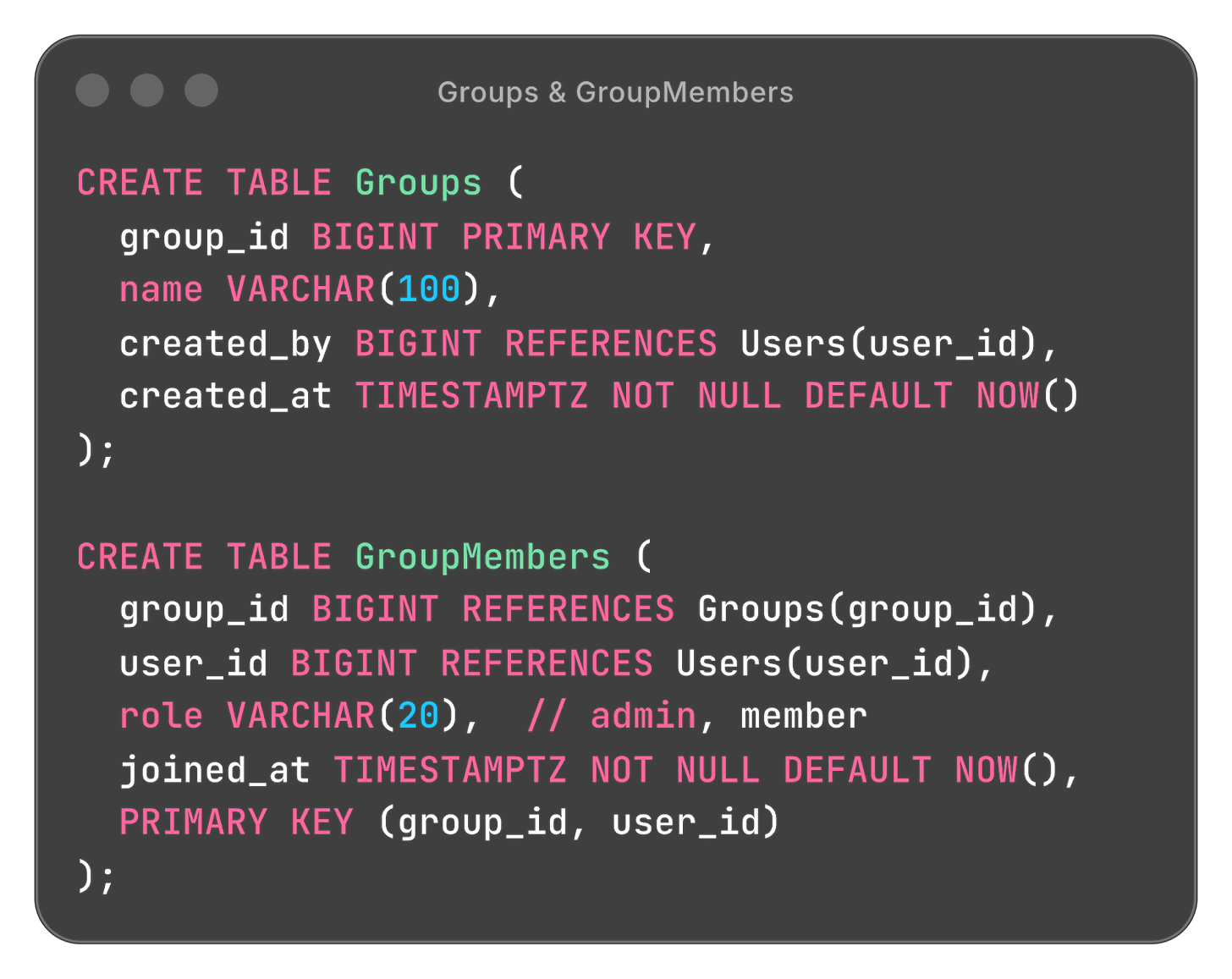

Messages Table (NoSQL - Cassandra)

Groups Table (SQL)

User Connection Registry (Redis)

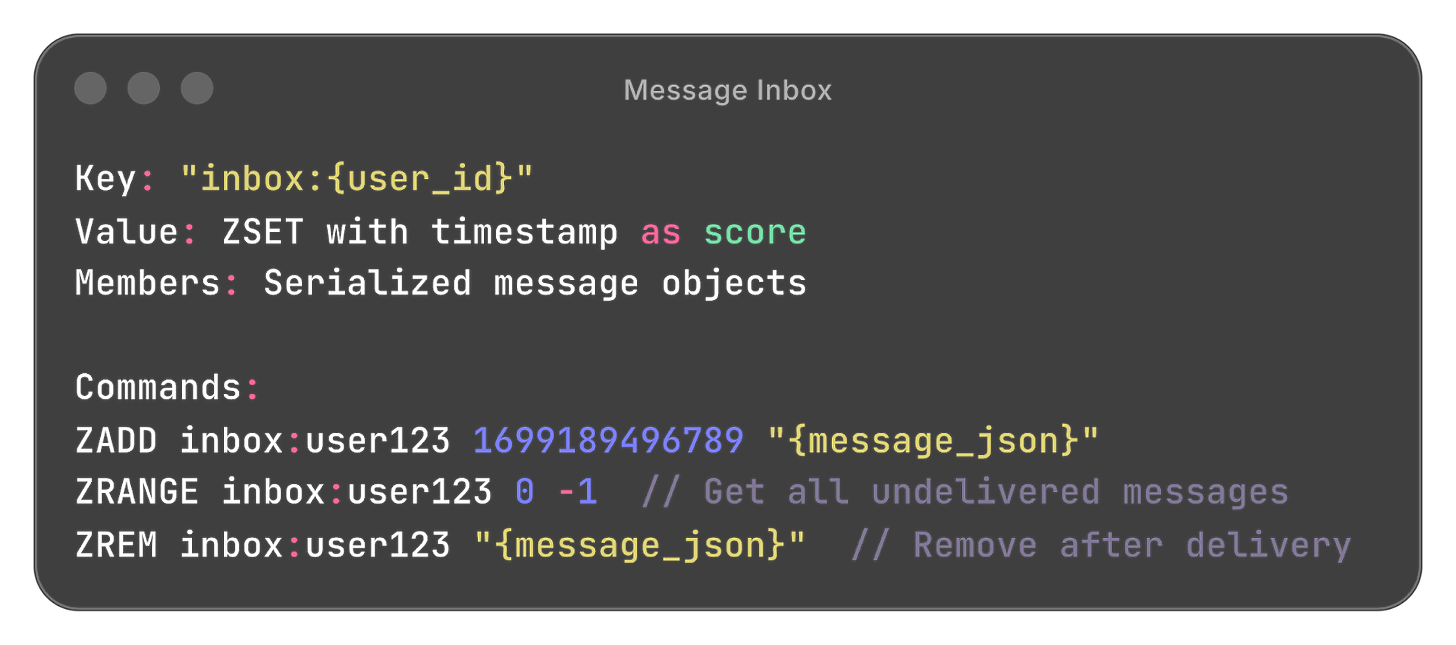

Message Inbox (Redis)

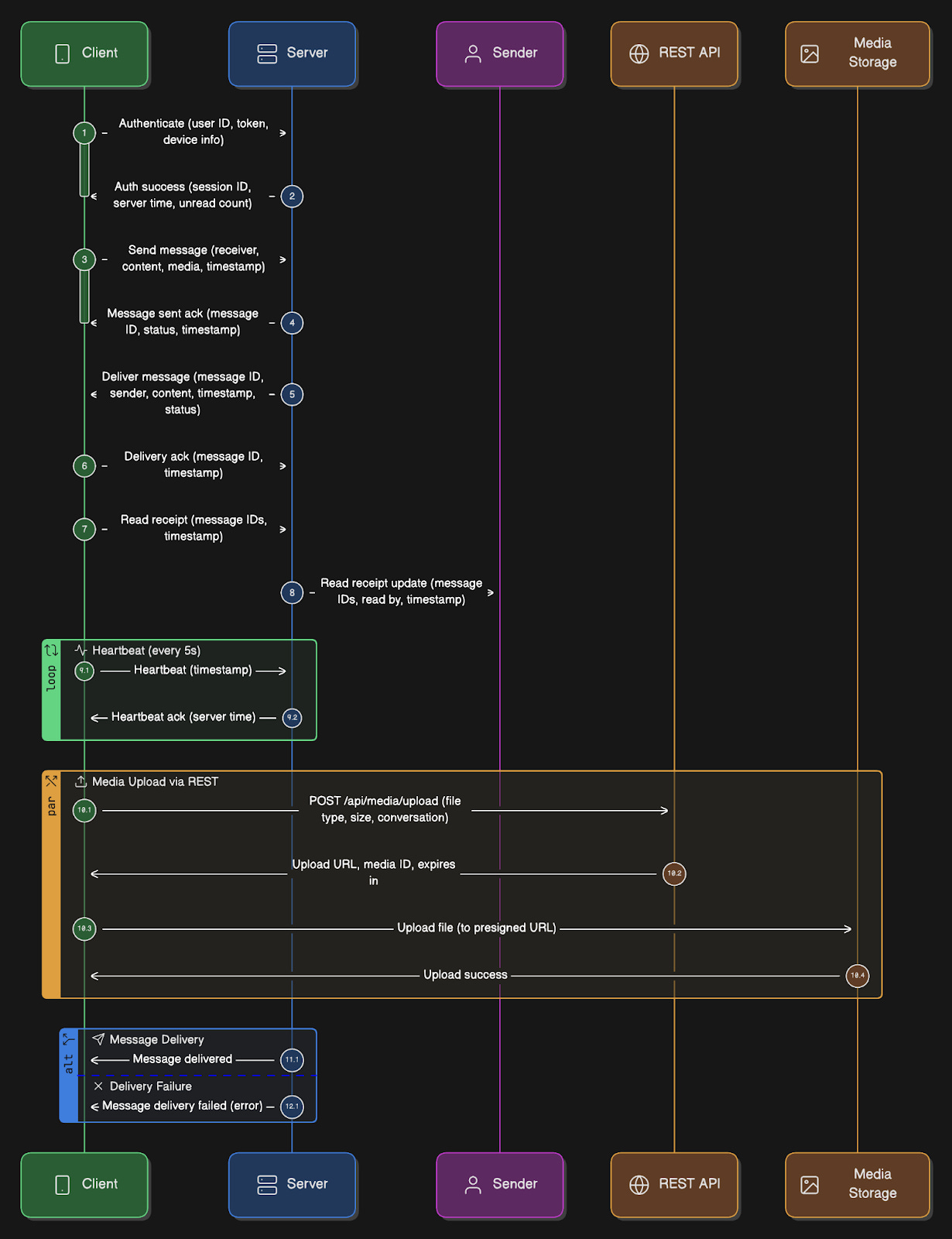

WebSocket and REST API Schemas

Now let’s get concrete with actual message formats:

WebSocket Connection Establishment:

Client -> Server (Initial handshake over WSS):

{

“type”: “auth”,

“payload”: {

“user_id”: “123”,

“auth_token”: “jwt_token_here”,

“device_id”: “phone-abc”,

“platform”: “ios”,

“app_version”: “2.24.5”

}

}

Server -> Client (Auth success):

{

“type”: “auth_success”,

“payload”: {

“session_id”: “sess_xyz789”,

“server_time”: 1699189200000,

“unread_count”: 47

}

}Sending a Message:

Client -> Server:

{

“type”: “message”,

“client_message_id”: “client_abc123”,

“payload”: {

“receiver_id”: “456”,

“content”: “Hey, are you free tomorrow?”,

“media_url”: null,

“reply_to”: null,

“timestamp”: 1699189200000

}

}

Server -> Client (ACK):

{

“type”: “message_ack”,

“client_message_id”: “client_abc123”,

“payload”: {

“message_id”: “20241105120000000001”,

“status”: “sent”,

“timestamp”: 1699189200123

}

}Receiving a Message:

Server -> Client:

{

“type”: “message”,

“payload”: {

“message_id”: “20241105120000000001”,

“sender_id”: “456”,

“receiver_id”: “123”,

“content”: “Yes, what time works for you?”,

“media_url”: null,

“timestamp”: 1699189200123,

“status”: “delivered”

}

}

Client -> Server (Delivery ACK):

{

“type”: “delivery_ack”,

“message_id”: “20241105120000000001”,

“timestamp”: 1699189200456

}Read Receipt:

Client -> Server (User opened chat):

{

“type”: “read_receipt”,

“message_ids”: [

“20241105120000000001”,

“20241105120000000002”,

“20241105120000000003”

],

“timestamp”: 1699189260000

}

Server -> Original Sender:

{

“type”: “read_receipt”,

“payload”: {

“message_ids”: [”20241105120000000001”, ...],

“read_by”: “123”,

“timestamp”: 1699189260000

}

}Presence Heartbeat:

Client -> Server (every 5 seconds):

{

“type”: “heartbeat”,

“timestamp”: 1699189200000

}

Server -> Client:

{

“type”: “heartbeat_ack”,

“server_time”: 1699189200123

}Media Upload Request:

Client -> Server (REST API):

POST /api/media/upload

{

“file_type”: “image/jpeg”,

“file_size”: 2457600,

“conversation_id”: “conv_123_456”

}

Server -> Client:

{

“upload_url”: “https://s3.amazonaws.com/bucket/signed_url...”,

“media_id”: “media_xyz789”,

“expires_in”: 3600

}Group Message:

Client -> Server:

{

“type”: “group_message”,

“client_message_id”: “client_def456”,

“payload”: {

“group_id”: “group_789”,

“content”: “Meeting at 3 PM”,

“media_url”: null,

“timestamp”: 1699189200000

}

}

Server fans out to all members, each receives:

{

“type”: “group_message”,

“payload”: {

“message_id”: “20241105120000000005”,

“group_id”: “group_789”,

“sender_id”: “123”,

“content”: “Meeting at 3 PM”,

“timestamp”: 1699189200123

}

}Ready for the best part?