What Makes an AI Agent Different From ChatGPT?

#111: AI Agents Explained: How They Go From Instructions to Action

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Imagine you maintain a scraper that checks flight prices every morning before your team’s standup.

It worked fine yesterday: navigate to the site, click the “Cheapest” toggle, collect results, and post to Slack. Simple and predictable.

Today, it fails… silently.

You dig in.

Airline redesigned its UI overnight. The button that said “Cheapest” now says “Lowest fare”, so your CSS selector points at nothing. The logic of your task (finding a cheap flight) remains valid. But your instructions assumed a world that no longer exists.

You fix it.

A week later, something else changes. You fix that, too. This is brittle automation; it works perfectly in narrow conditions but breaks if anything shifts.

Consider a different approach:

Instead of writing code that clicks a specific element, you give an AI agent1 a goal: “Find the cheapest flight to Tokyo this month”.

In the best case, the agent can infer that “Lowest fare” is equivalent to “Cheapest” and choose the right control2. Semantic robustness doesn’t happen automatically. Without explicit fallbacks and label-matching strategies, agents fail when UIs change. Even minor layout shifts, pop-ups, or accessibility features break them.

Comparing Agents against Robotic Process Automation (RPA) helps…

RPA scripts follow predetermined steps, while agents try to understand what they see. But agents still depend on page structure and labels, not real human understanding, so they break on messy pages.

This is the shift:

Instead of telling software how to do something step by step, you tell it what you want. The agent figures out how.

That’s not magic.

Behind the scenes, the agent breaks your goal into steps, tries them out, watches the results, and adjusts. When something fails, it can retry if you’ve set up error handling and backup plans. Without those, agents often loop on the same failure or stop at a step limit.

The difference from traditional code isn’t that agents are smarter. It’s that they’re designed to navigate ambiguity rather than demand certainty.

In this newsletter, we’ll open the hood on how agents actually work.

We’ll follow one example: booking a flight.

This will show how agents work, how they think, what tools they use, how they remember, and what breaks in real use. By the end, the mystique should be gone.

You’ll see the machine for what it is.

Onward.

🎁 Giveaway Alert (Valid for 24 hours only)!

Win a copy of the software engineering classic book—The Pragmatic Programmer.

To get it for FREE:

Sign up for CodeRabbit by clicking here

Fill out this tiny form

(Three winners will be selected at random.)

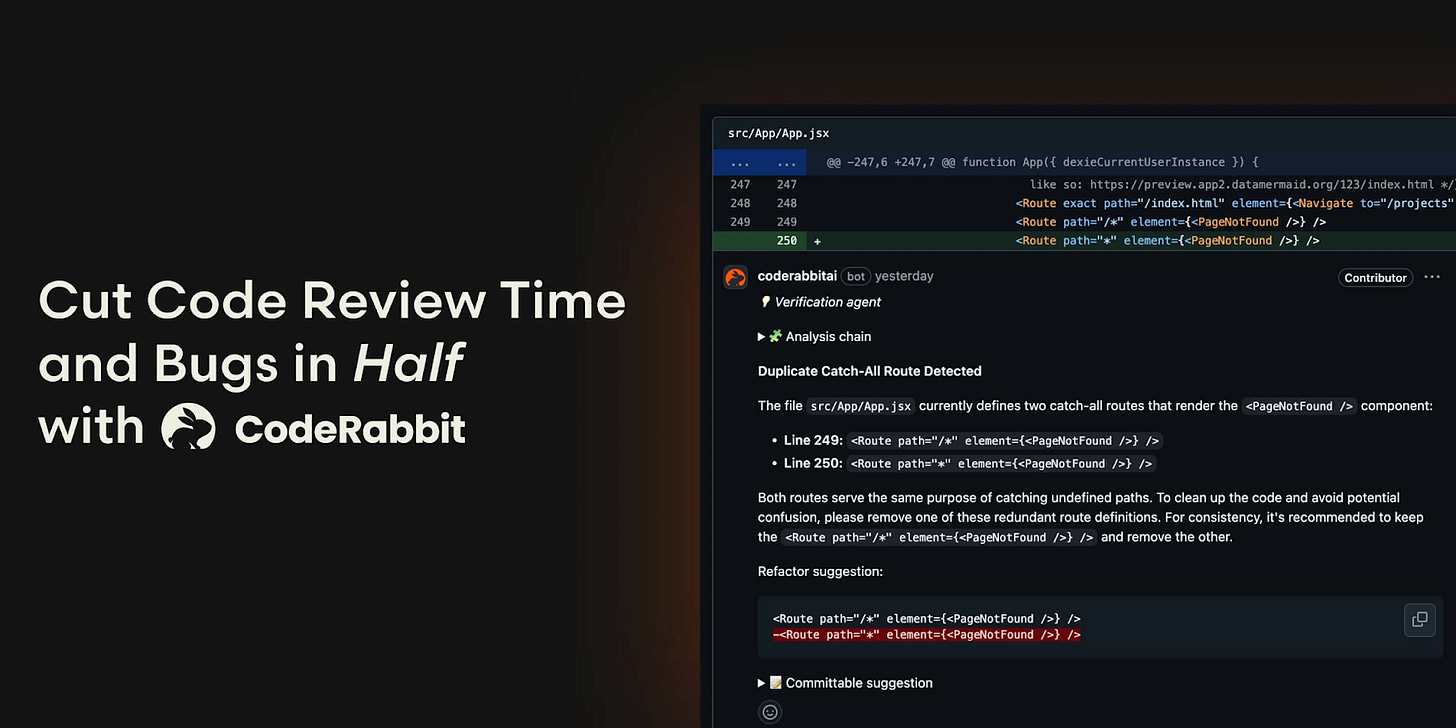

Cut Code Review Time & Bugs in Half (Sponsor)

Code reviews are critical but time-consuming.

CodeRabbit acts as your AI co-pilot, providing instant Code review comments and potential impacts of every pull request.

Beyond just flagging issues, CodeRabbit provides one-click fix suggestions and lets you define custom code quality rules using AST Grep patterns, catching subtle issues that traditional static analysis tools might miss.

CodeRabbit has so far reviewed more than 10 million PRs, has been installed in 2 million repositories, and has been used by 100 thousand open-source projects. CodeRabbit is free for all open-source repos.

I want to introduce Sairam Sundaresan as a guest author.

He’s an AI engineering leader with 15+ years of experience building AI and ML systems in industry. He likes to teach AI through illustrations and stories, and he turned the same style into a published Bloomsbury book, AI for the Rest of Us.

Check out his book and writing:

These days, he leads AI work, advises teams on practical systems, and writes and illustrates to make AI feel less like magic and more like engineering.

What Is an Agent?

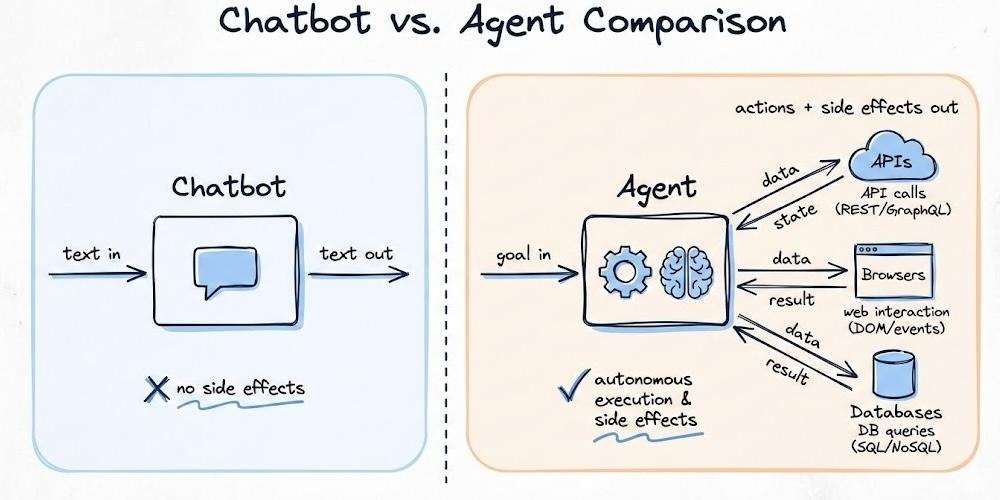

Start with the simplest distinction: a chatbot talks; an agent does.

Ask a ‘chatbot’ to book you a flight, and it explains how: what to search, what to compare, maybe a link. Helpful, but nothing changes.

Ask an ‘agent’ to book a flight. It opens a browser, calls APIs, compares prices, and filters results based on your constraints. It checks whether seats are available. If a payment error happens, it tries again. Once successful, it confirms the booking and sends you the receipt. When it’s done, you'll have a ticket.

That side effect (changing the world) is what separates agents.

The Digital Intern

A helpful way to think about agents: treat them like a smart but inexperienced intern.

You wouldn’t micromanage an intern’s keystrokes. Instead, you’d say:

“Book me a flight to Tokyo, under $500, in the next month. Use the corporate card. Email me the confirmation.”

You set the goal and give the agent what it needs to work: access to the travel site, payment details, and an email address. You also set limits, such as your budget, airline preferences, and a rule against red-eye flights. They figure out the rest…

An agent works the same way.

You don’t script every click. You specify what success looks like and what’s off-limits. The agent handles the intermediate decisions.

But here’s the caveat the analogy misses: an intern makes mistakes at human speed. One task, natural pauses, is easy to catch.

An agent’s mistakes scale instantly. Give it access to your email with a vague instruction like “follow up with leads,” and it might send 200 bizarre messages before anyone notices.

Agents need real boundaries enforced in code: rate limits, allow lists, and verification gates. Telling them in prompts isn’t enough.

What Makes Something an Agent

Three characteristics define the difference:

1. Autonomy

It means the agent figures out intermediate steps on its own. You said, “Book a flight under $500.”

The agent determines what needs to happen.

Things fail: airline sites time out, fares disappear. The agent can adapt if you’ve given it recovery strategies. Otherwise, it gets stuck or keeps trying the same thing.

2. Proactiveness

It means taking the initiative when information is missing.

Imagine the agent finds two flights at the same price with different layovers:

Can it check your calendar or ask you? Only if you’ve permitted it and told it to ask questions. Otherwise, it picks randomly. It doesn’t just guess and hope.

Recognition of missing input is a design feature (e.g., uncertainty thresholds and “ask‑for‑help” triggers), not an innate property.

3. Action

Taking action through tools distinguishes agents from chatbots.

An agent calls APIs, automates browsers, executes code, and sends emails. Of course, it’s subject to strict scoping and validation. These capabilities are mediated through defined interfaces: tools with clear inputs and outputs.

The agent decides what to do; the tools make it happen in the real world.

Specifying Your Agent: A Checklist

Before you build, you need to answer four questions…

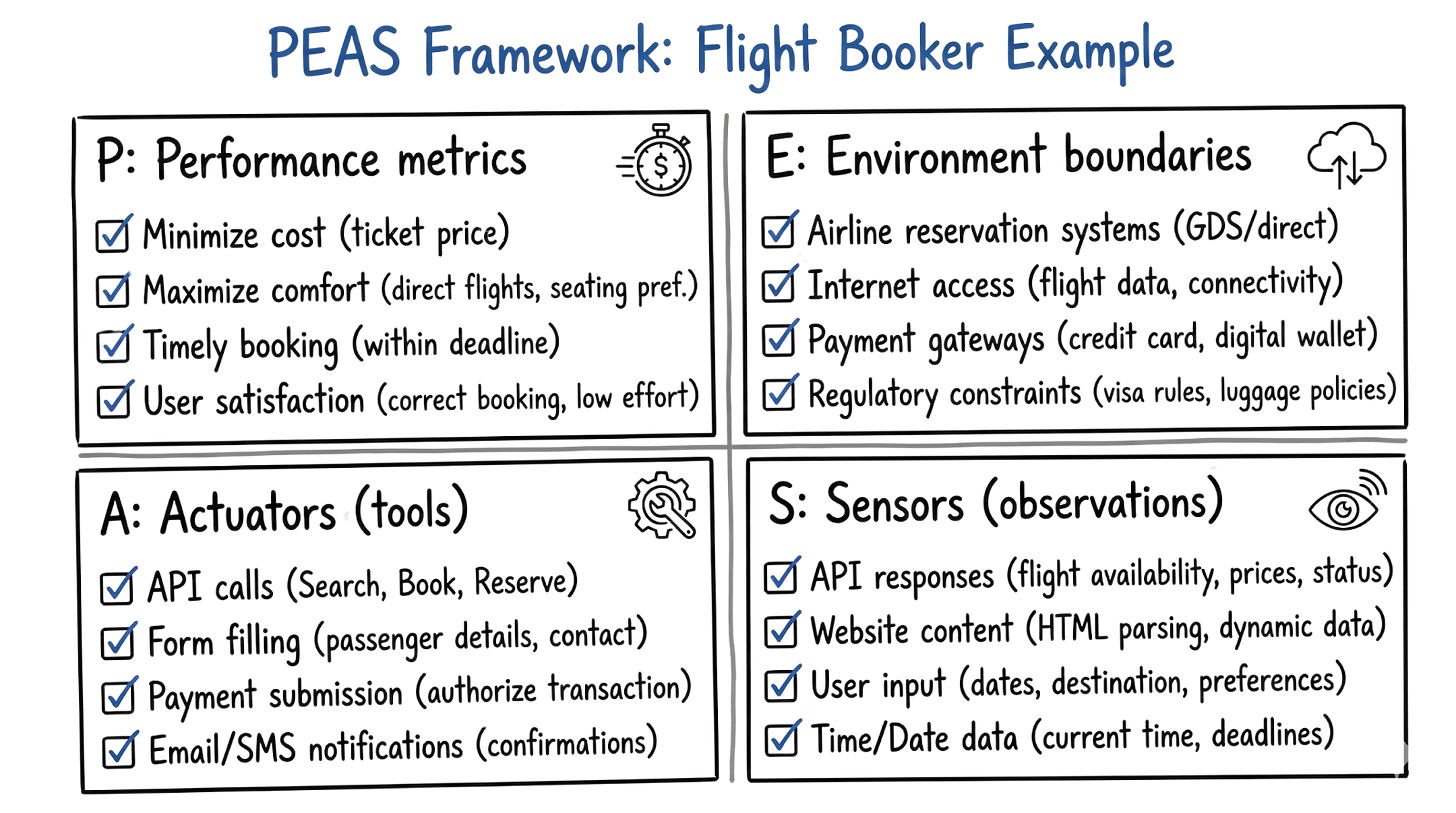

There’s a framework from classical AI called PEAS that makes this concrete.

Using our flight booker example:

1. Performance:

How do you know it worked?

“Round-trip to Tokyo, under $500, departing within 30 days, confirmation email received.”

2. Environment:

Where does it operate? Public airline sites, a flight aggregator API, and your corporate email system.

What’s in bounds, what’s not? Can it access your calendar? Your credit card? Define the playing field.

3. Actuators:

What can it do? Search flights, click buttons, fill forms, make purchases, and send emails.

Each capability is a tool you’re handing over. More tools mean more power, and more risk.

4. Sensors:

How does it perceive the results? Reading page content, parsing API responses, and detecting confirmation numbers in emails.

If it can’t observe the outcome of an action, it can’t reason about what to do next.

Get these wrong, and the agent wanders! Get them right, and you have a system you can actually build and debug.

The Brain

A common mistake: treating Large Language Model3 (LLM) as a knowledge base.

Think of the LLM as a processor, not as a hard drive. It takes input, reasons, and produces output. Unlike a CPU, it’s probabilistic: good with messy language, imperfect with precise facts.

For our flight booking agent, this means: don’t expect the LLM to “know” which airlines fly to Tokyo or current prices. It doesn’t.

Instead, it can propose next steps: search for flights, compare prices, and check seat availability. It can try to interpret what it sees.

But this breaks easily on complex pages. You fix this by using APIs instead of raw HTML, adding accessibility features, and setting guardrails.

The practical implication: the LLM is the reasoning engine, not the source of truth.

When your agent needs facts (current prices, seat availability, your company’s travel policy), it gets them from tools and memory. The LLM’s job is to figure out what to look up, how to interpret results, and what to do next. Reasoning, not retrieval.

Living with Non-Determinism

Ask an LLM the same question twice, and you might get different answers.

Not wrong answers, just different phrasings, different emphasis, occasionally different conclusions. This isn’t a bug. It’s how probabilistic systems work.

You can dial this down.

A parameter called “temperature” controls randomness: lower means more predictable. But you’ll never get the perfect repeatability of traditional code, and that’s okay.

This means you design differently:

For ‘low-stakes’ decisions (which search results to show first), variance is fine.

For ‘high-stakes’ actions (actually purchasing a flight), you add verification.

Before the agent charges your card, it should confirm key details: flight, price, and total. Then proceed. The fuzzy reasoning can propose actions. The final execution needs checkpoints4.

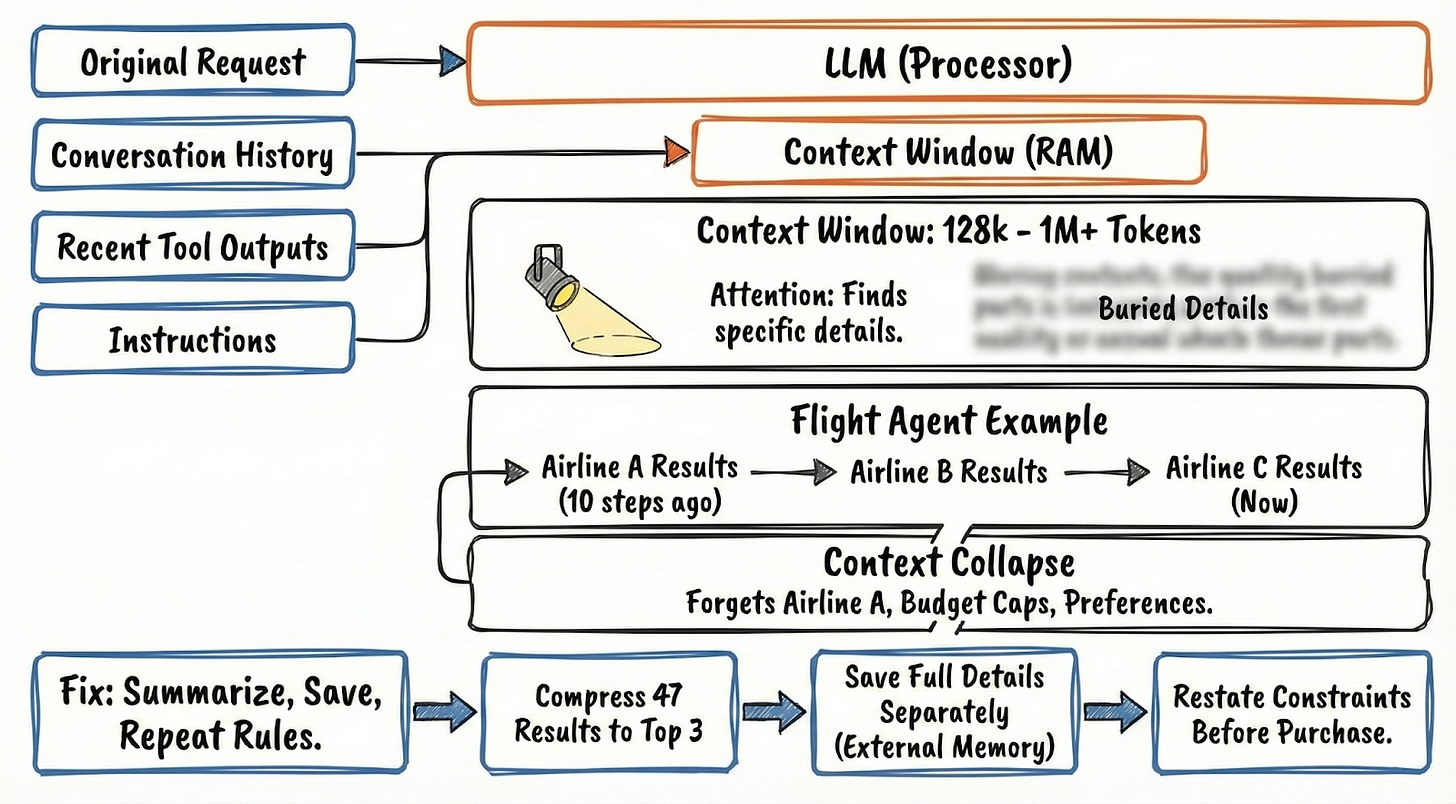

The Context Window: Working Memory

If the LLM is the processor, the context window5 is its RAM.

This is everything the agent can ‘see’ at once. It includes your original request, the conversation so far, recent tool outputs, and any instructions you’ve given it.

Current models range from around 128,000 to over 1 million tokens of context. Running out of space isn’t the main concern anymore.

The real limit is attention:

As the context grows, the agent has trouble finding and using specific details buried in the middle.

Your flight agent searches three airlines. Each returns a page of results: flight times, prices, layovers, seat classes. Add the original instructions, the reasoning so far, and suddenly you’re managing memory.

When the context window fills up, the agent effectively forgets. Old information drops off. If the agent searched Airline A ten steps ago and now needs to compare it to Airline C, those Airline A results might be gone.

Context collapse is a major problem…

The agent loses track of earlier constraints, such as budget caps or airline preferences.

Fix this by summarizing information, saving details separately, and repeating your key rules at each step.

Here’s how it works with flights:

Compress 47 results into the top 3 that fit your budget.

Save full details separately.

Restate your constraints before the agent completes the purchase.

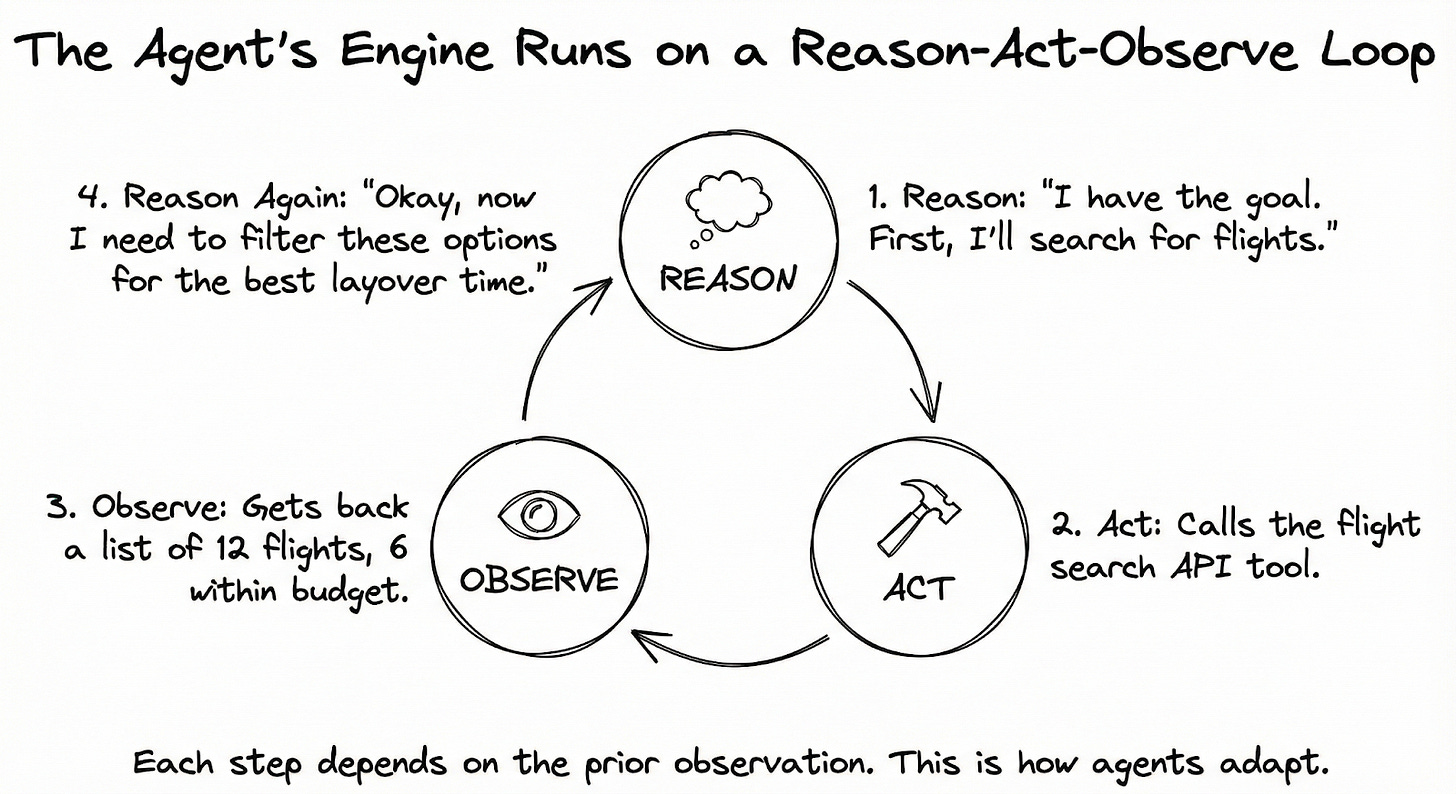

The Loop

The engine that makes agents work is called ReAct6: Reason plus Act.

It’s simpler than it sounds.

Let’s trace it through our flight booking:

You’ve told the agent: “Book me a round-trip flight to Tokyo, under $500, in the next month.”

The agent doesn’t immediately start clicking around. First, it reasons: “Tokyo, under $500, flexible dates. I’ll search flights first.”

Then it acts: it calls the flight search API with the following parameters (destination: Tokyo, dates flexible, max price: $500).

The API returns results. But these results don’t go straight to you. They go back to the agent for an observation. The agent now sees: “12 flights found. Prices range from $420 to $890. Six are within budget.”

Now it reasons again: “I have options within budget. But I should check which ones have good layover times. Let me filter for flights under 20 hours’ total travel time.”

It acts again: filters the results, or maybe calls another tool to get more details on the top candidates.

This cycle (reason, act, observe, reason again) continues until the agent reaches the goal:

Search flights.

Observe results.

Filter options.

Observe the filtered list.

Check seat availability on the top choice.

Observe that seats exist.

Initiate purchase.

Observe confirmation.

Send email.

Done.

The key insight:

Agent isn’t following a pre‑written script; each step depends on prior observations.

ReAct helps agents adapt, but it’s not reliable.

Early mistakes (misread prices, missed constraints) pile up and break later steps. Mitigate with checkpoints, structured plans for known phases, and verification before irreversible actions.

When the Path Is Known

ReAct shines when things are uncertain:

Will the search find anything?

Are seats available?

What errors will pop up?

You don’t know, and ReAct can adapt. But sometimes you know exactly what needs to happen.

An alternative pattern is called Plan-and-Execute7.

The agent writes out a complete plan upfront:

Search Tokyo flights for next month.

Filter for under $500.

Rank by total travel time.

Check seat availability on the top 3.

Book the best available.

Email confirmation.

Then it executes each step in sequence.

This is faster: fewer round-trips to the LLM, less “thinking” between steps. And the plan is reviewable. You can see what the agent intends before it starts.

The downside: rigidity.

If step 3 reveals something unexpected (say, all flights under $500 have 30-hour layovers), the plan doesn’t adapt. The agent isn’t reasoning between steps, so it can’t course-correct without scrapping the plan and starting over.

The Hybrid Approach

In practice, most systems combine both:

You create a plan with clear checkpoints and ways to handle failures. Within each checkpoint, you let the agent think through problems, but with limits.

“Search and filter” is one phase; within that phase, the agent uses ReAct to handle the messiness of search results.

“Book and confirm” is another phase; again, ReAct handles the payment flow, error recovery, and confirmation.

You get the structure of a plan with the adaptability of dynamic reasoning.

The flight agent knows the overall shape of what it’s doing, but can navigate surprises within each segment.

Checkpoints are up to you. You might add one between search and purchase, where a human or system verifies the choice before buying. Without it, runaway errors are common.

Tools and Memory

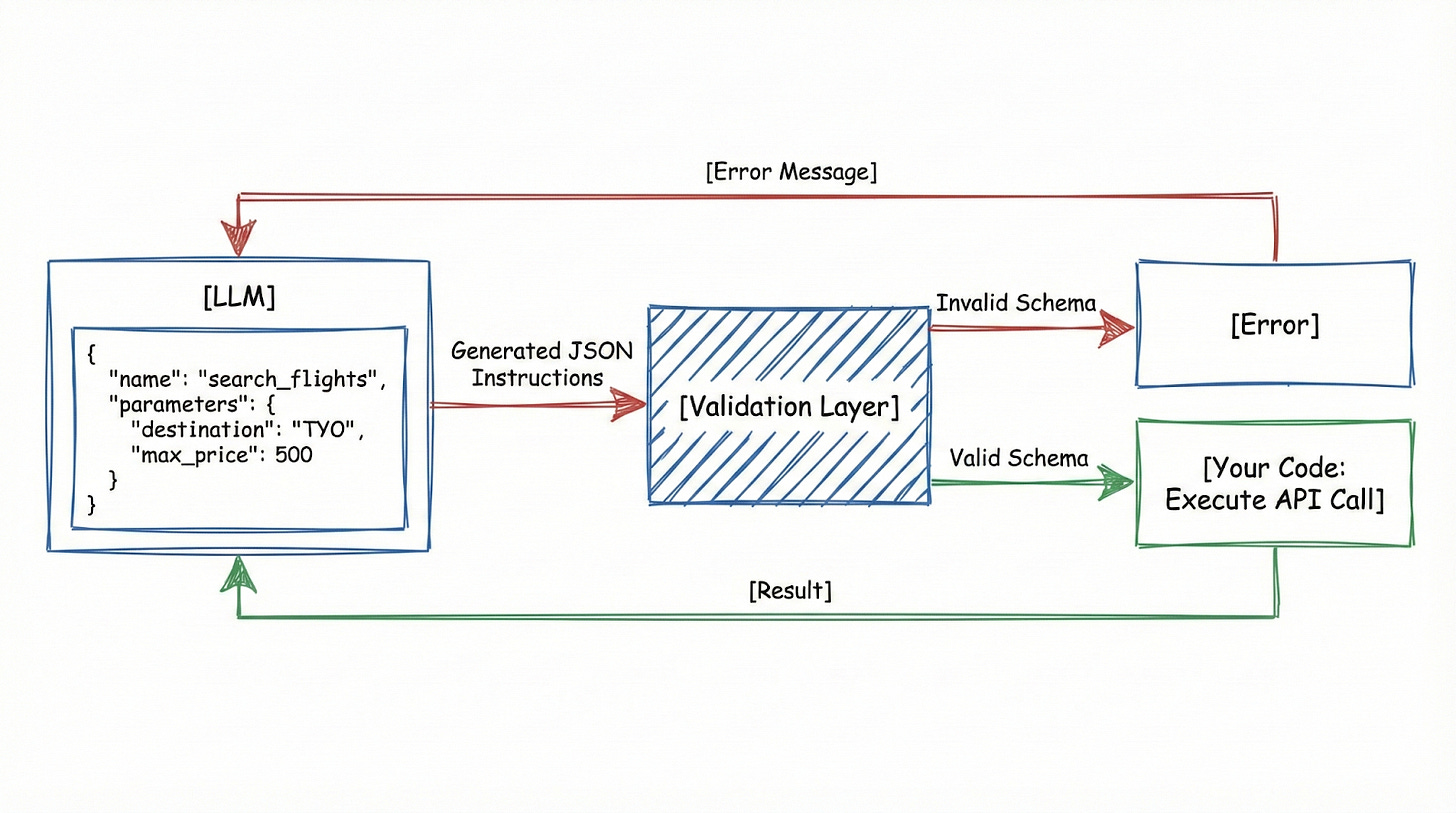

An LLM by itself can only produce text.

To actually book a flight (to search, click, purchase, email), it needs tools8.

Here’s what actually happens when an agent uses a “tool”:

The LLM doesn’t browse the web or execute code directly. Instead, it uses native tool calling. You define a set of allowed functions in your API request, and the model switches into a specialized mode to “call” them.

It stops writing and makes a structured request.

It asks for a specific function and provides the exact information it needs.

External code then takes that JSON, validates it, executes the real operation, and returns the result.

For our flight agent, you might define a tool like this:

{

“name”: “search_flights”,

“description”: “Search for available flights”,

“parameters”: {

“origin”: “string”,

“destination”: “string”,

“departure_date”: “string”,

“return_date”: “string”,

“max_price”: “number”

}

}When the agent decides to search for flights, it doesn’t somehow access an airline’s website. It outputs:

{

“name”: “search_flights”,

“parameters”: {

“origin”: “SFO”,

“destination”: “TYO”,

“departure_date”: “2025-01-15”,

“return_date”: “2025-01-22”,

“max_price”: 500

}

}Your code receives this:

Validates it

Are all required fields present?

Are the types correct?

Calls the actual flight API.

And returns results to the agent.

Sometimes the agent makes up parameters, like asking for ‘seat preference: window’ when that option doesn’t exist. Good schema validation catches this and returns an error.

The system should then try a different approach rather than just repeating the same mistake.

Memory: Beyond the Conversation

The context window is the agent’s short-term memory: what it can hold in mind during a single task.

But what about information that spans sessions or exceeds what fits in context?

This is where “external memory” comes in.

The dominant approach is called RAG9 (Retrieval-Augmented Generation). Don’t load everything into the context window at once. Store information in a database and fetch only what’s relevant for what the agent is doing right now.

For our flight agent, imagine it needs to check your company’s travel policy:

The full policy is 50 pages, way too much for context. Instead, the policy is stored in a vector database10. When the agent needs to know the maximum flight budget for Asia, it searches the database.

The database returns the relevant section: “Asia-Pacific travel: economy class, maximum $600 per segment, advance booking required.”

That excerpt gets injected into the context. The agent reasons with it, then moves on.

The interesting part is how retrieval works:

Traditional databases match keywords. Vector databases match meaning. They convert text into numbers. Similar concepts end up close together in this number system. This means ‘budget limit’ and ‘maximum cost’ are treated as similar ideas.

When you search for ‘budget’, you’ll find sections about ‘maximum cost’, even if they don’t use the word ‘budget’.

This approach lets agents handle lots of information without overloading the system.

Company policies, past bookings, and user preferences are all stored separately and retrieved only when needed. The agent knows how to ask for what it needs. The retrieval system finds it.

For flight booking, memory might include:

Short-term: current search constraints, options found so far, steps taken

Long-term: your airline preferences (aisle seat, no red-eyes), corporate travel policy, past trips, and their costs

The agent accesses long-term memory as needed. Short-term memory stays focused on the current task.

When the context window fills up, the agent summarizes or discards older information.