I struggled to code with AI until I learned this workflow

#119: AI coding workflow

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Everyone talks about using AI to write code like it’s a vending machine:

“Paste your problem, get a working solution.”

The first time I tried it, I learned the hard way that this is not how it works in real projects…

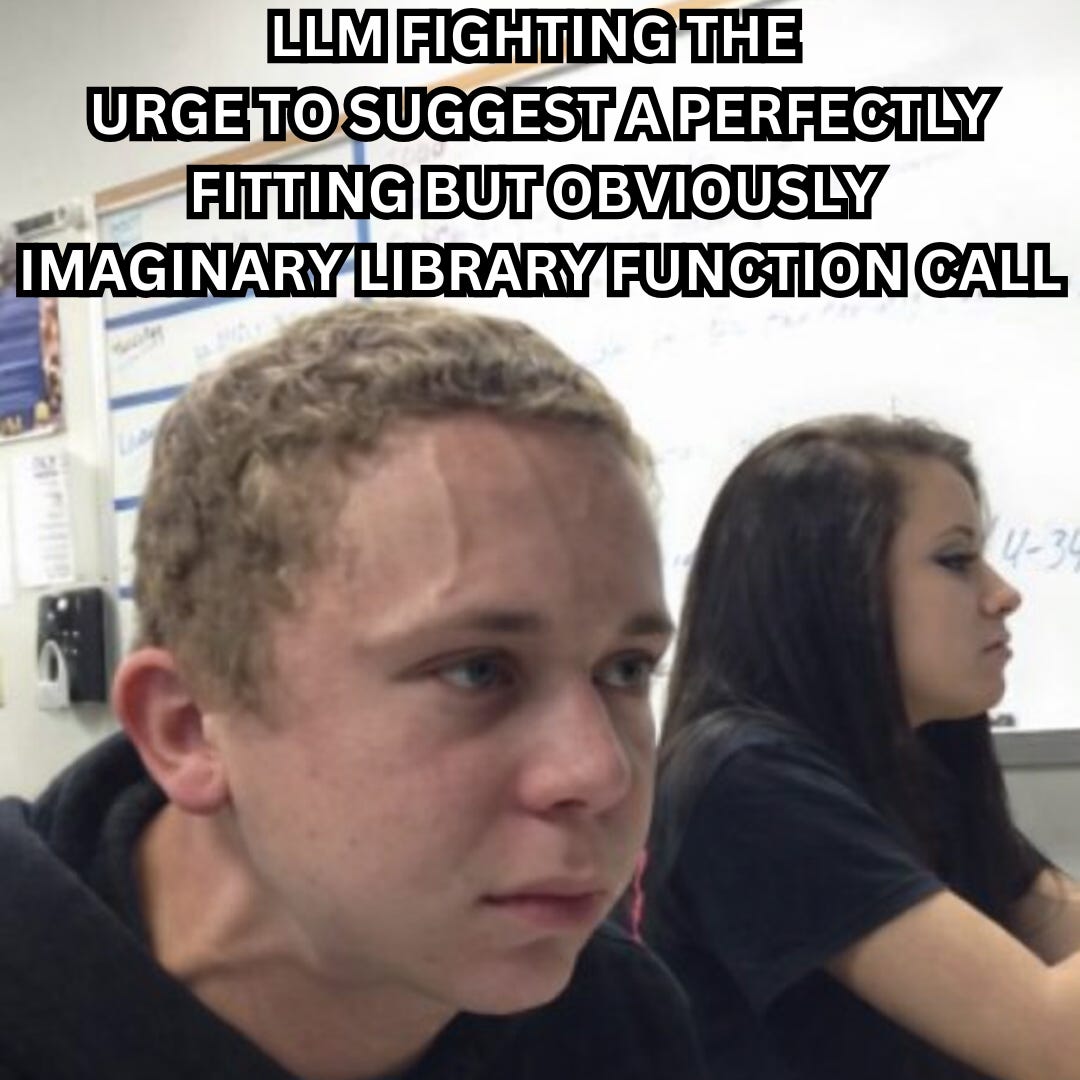

The model would confidently suggest code that called functions that didn’t exist, assumed libraries we weren’t using, or skipped constraints that felt obvious to me1. The output looked polished.

The moment I ran it… It fell apart.

After enough trial and error, I stopped trying to “prompt better” and started working differently. What finally made AI useful wasn’t a magic tool or a clever prompt. It was a simple loop that kept the model on a short leash and kept you in the driver’s seat:

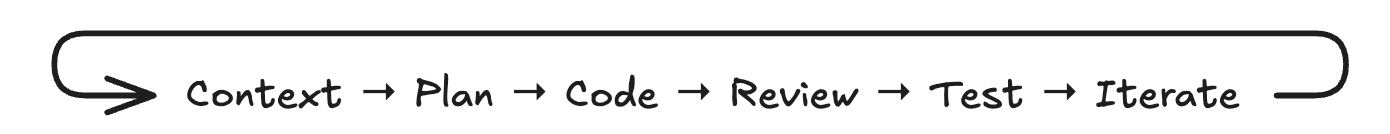

This newsletter breaks that loop down step by step.

It’s written for software engineers who are new to AI coding tools and want a practical starting point: not a tour of every product on the market, but a repeatable method you can use tomorrow.

The core idea is simple:

AI works best as an iterative loop, not a one-shot request. You steer. The model fills in the gaps. And because it does less guessing, you spend less time cleaning up confident mistakes.

Onward.

I’m happy to partner with CodeRabbit on this newsletter. Code reviews usually delay feature deliveries and overload reviewers. And I genuinely believe CodeRabbit solves this problem.

I want to introduce Louis-François Bouchard as a guest author.

He focuses on making AI more accessible by helping people learn practical AI skills for the industry alongside 500k+ fellow learners.

TL;DR

If you’re new to using AI for coding, this is the set of habits that prevents most pain.

Treat AI output like a draft, not an answer. Models can sound certain while being completely wrong, so anything that matters still gets reviewed and verified.

Start with context, the way you’d brief a teammate. If you don’t share constraints, library versions, project rules, and intended behavior, the model will ‘happily’ invent them for you.

Ask for a plan before you ask for code. Plans are cheap to change. Code is expensive to unwind. I’ll usually approve the approach first, then ask for small, step-by-step changes.

Use reviews and tests as a safety net. I still do a normal pull request2 review and rely on tests to verify behavior and catch edge cases3.

Quick Glossary

Before we dive in, here’s the small vocabulary I’ll use throughout.

It’s not exhaustive; it’s just enough to keep the rest of the article readable:

AI Editor (e.g., Cursor, VS Code + GitHub Copilot) is a code editor with AI built in. It can suggest completions, refactor functions4, and generate code using your project files as context.

Chat model (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini) is a conversational AI you interact with in plain language. It’s useful when you’re still figuring out what to do: brainstorming approaches, explaining an error, comparing trade-offs, or sanity-checking a design before you write code.

AI code review tools (e.g., CodeRabbit) automatically review pull requests using AI, posting summaries and line-by-line suggestions.

Search assistant (e.g., Perplexity) combines chat with web search. It’s what you reach for when you need to verify that a suggested API call is real, that a library feature exists in the version you’re using, or that you’re not about to copy-paste something that expired two releases ago.

The Mental Model

Before the workflow, it helps to be honest about what AI coding assistants are and aren’t.

They’re fantastic when the problem is well-scoped and sitting right in front of them. They’re unreliable the moment you assume they “know” what you didn’t explicitly provide. The workflow is basically a way to stay in the first zone and avoid the second.

When you give clear requirements, AI is great at drafting functions, refactoring code, scaffolding tests, and talking through error messages.

But it has a hard boundary: it only knows what it can see in the current context. It doesn’t remember your last chat; it doesn’t know your architecture or conventions, and it won’t reliably warn you when it’s guessing. It just keeps going confidently.

I’ve seen AI call library functions that don’t exist, use syntax from the wrong version, and ignore constraints I assumed were obvious. The pattern was always the same: the AI didn’t know what I hadn’t told it, so it filled the gaps by inventing something plausible.

Once I understood this, three principles shaped how I work:

1. Give more context than you think you need. Just like I’d brief a colleague who just joined the project, I brief the AI every time. If I don’t share the details, it invents them.

2. Guide it with specific steps. AI struggles with “build me a web app,” but does well with “add input validation for these fields, return a clear error message, and write a test that proves invalid input is rejected.” The more specific my request, the better the output.

3. If it matters, verify it. Whenever the AI produces security-sensitive logic, a database migration, or an algorithm that must be correct, I review it myself and add tests that prove the behavior.

A good way to hold all of this in your head is:

AI is a smart teammate who joined your project five minutes ago.

They can write quickly, but they don’t know your architecture, your conventions, or your constraints unless you tell them.

That’s why the mistakes look so predictable: the model isn’t “being dumb,” it’s filling in gaps you didn’t realise you left open.

Once I started seeing it that way, the fix wasn’t a better one-shot prompt5.

It was a repeatable loop that forced me to brief the model, force clarity early, and keep changes small enough to verify.

I’m not sure if you're aware of this…

When you open a pull request, CodeRabbit can generate a summary of code changes for the reviewer. It helps them quickly understand complex changes and assess the impact on the codebase.

Speed up the code review process.

The Workflow

The loop is the same whether I’m fixing a bug, adding a feature, or cleaning up a messy module.

It keeps the AI from freelancing, and it keeps me from treating “code that looks plausible” as “code that’s ready to ship.”

Here’s the loop:

Context: I share project background, constraints, and the relevant code so the AI isn’t guessing.

Plan: I ask for a strategy before any code gets written.

Code: I generate or edit code one step at a time, so changes stay small and reviewable.

Review: I carefully check the output and often use AI-assisted pull request reviews as a second set of eyes.

Test: I run tests, and I’ll often have AI generate new tests that lock in the intended behavior.

Iterate: I debug failures, refine the request, and repeat until the change is solid.

I use different tools at different points in the loop.

Each one is good at a specific job:

An editor is good at working inside a repo,

A chat model is good at thinking in plain language,

And review/testing tools are good at catching things I’d miss when I’m tired.

The rest of this newsletter breaks down each step.

The most important step is the first one:

If the model is guessing about your setup, everything downstream becomes cleanup. So the workflow starts with context.

Step 1: Context

Most AI mistakes in code have the same root cause.

The model is guessing in a vacuum. Someone pastes a function, types “fix this,” and acts surprised when the suggestion ignores half the system.

“Fix this” is the fastest way to make the model hallucinate…

Without a project background and constraints, it has no choice but to fill gaps with whatever sounds right: ‘functions that don’t exist, syntax from the wrong version, solutions that break conventions elsewhere in the repo’.

So, for anything that is not small, I flip the default: documentation and rules go first. Code goes second.

This is easiest with an AI editor that can automatically pull in files.

I use Cursor, which lets me highlight code, pull in other files from my project, and ask the AI to do specific work with all of that as context. The pleasant part is I can swap models on the fly: a fast one for quick edits, a heavier reasoning model when I need to solve a tricky bug.

VS Code with Copilot or Claude Code offers similar features if you prefer to stay in that ecosystem.

When a task is even moderately complex, I load three kinds of context:

1. Project background

I keep an updated README6 for each project and start most AI sessions by attaching it with a simple opener:

Read the README below to understand the project. Then I will give you a specific task.If the change touches something sensitive (like payments), I include the key files in that first message too. By the time I describe the change, the assistant has already seen the neighborhood.

2. Rules and constraints

I keep a rules file (sometimes called AGENTS.md or CLAUDE.md)7 that bundles project scope, coding style, version constraints (for example, “this service runs on Django 4.0”), and a few hard rules (“never call this external API in development,” “all dates must be UTC”).

Some tools support “rules” or “custom instructions” that help me avoid repeating myself in every session.

3. Relevant source and signals

For bugs or features, I paste the function or file involved along with stack traces8 or logs.

A single error line is like a screenshot of one pixel. The assistant needs more than that if I want real reasoning instead of optimistic guessing.

Here’s a reusable prompt pattern:

Read @README to understand the project scope, architecture, and constraints.

Read @AGENTS.md to learn the coding style, rules, and constraints for this codebase.

Then read @main.py, @business_logic_1.py, and @business_logic_2.py carefully.

Your task is to update @business_logic_2.py to implement the following changes:

1. <change 1>

2. <change 2>

3. <change 3>

Follow the conventions in the README and AGENTS file.

Do not modify other files unless strictly necessary and explain any extra changes you make.The structure stays the same every time: context, then rules, then a precise task.

I swap out the filenames and the change list, but the pattern holds.

One thing I learned the hard way: more text isn’t always better. The best briefings are short and focused. They explain what the project is for, how the main pieces fit together, and which rules actually matter. If I notice I’m pasting more than a human would reasonably read before starting work, I cut it down.

One final detail that matters: context should be curated… not dumped.

The best briefings are short and decisive, enough to prevent guessing, but not so much that the model loses the signal. If I’m pasting more than a human would reasonably read before starting, I cut it down.

Step 2: Plan Before You Code

Context answers “where am I?”

It doesn’t answer “what should I build?”

That’s where things usually go sideways.

If you let AI write code immediately, it often picks a strange approach, optimizes the wrong thing, or quietly ignores constraints.

I’ve learned to force a two-step process: plan first, then code.

I usually do the planning step in a chat model like Claude, ChatGPT, or Gemini. ChatGPT works well when the problem is fuzzy, and I need structured thinking. Once the design feels reasonable, I switch to an AI editor like Cursor or Claude Code in VS Code, where the implementation happens with the repo open.

First: Ask for a plan only

For any non-trivial change, I first describe the feature or bug in plain language. That initial exchange is just about getting the idea into a workable shape:

Here is the feature I want to build and some context.

Help me design it.

What needs to change?

Which modules are involved?

What are the main steps?The key is to stop the AI from jumping straight into code. I’ll often say explicitly, “Do not write any code until I say approved.”

Then: Approve and implement in small steps

Once the plan looks reasonable, I approve it and ask the AI to implement one step at a time.

This is where I usually switch from a chat model to an AI editor like Cursor or VS Code with Copilot, since the implementation happens inside the actual codebase. For each step, I ask the AI to explain what it’s about to change and propose the code for that step only.

Small steps are easier to review and easier to undo if something goes wrong.

Here’s a prompt template I reuse:

You are a senior engineer helping me with a new change.

First, read the description of the feature or bug:

<insert feature or bug description and any relevant context>

Step 1 — Plan only:

- Think step by step and outline a clear plan.

- List the main steps you would take.

- Call out important decisions or tradeoffs.

- Mention edge cases we should keep in mind.

Stop after the plan. Do not write any code until I say “approved.”

Step 2 — Implement:

Once I say “approved,” implement the plan one step at a time:

- For each step, explain what you are about to change.

- Propose the code changes for that step only.

- Write tests for that step where it makes sense.If the AI recommends a library or function I’ve never seen, I’ll verify it actually exists using a search assistant or official docs. Models sometimes hallucinate APIs that sound plausible but don’t exist.

This pattern is especially useful when I’m working in a new stack or unfamiliar codebase. Instead of reading docs for hours, I ask the AI to explain the stack, sketch a design, and then help me implement it. The AI explains before it writes, so I learn as I go.

It also helps when a change touches multiple parts of the system, since a plan lets me see the full scope before I make edits everywhere.

Same with subtle bugs I don’t fully understand. For a slow database query, instead of asking “make this faster,” I ask the AI to reason through why it might be slow and what options exist. Only after that reasoning do I ask for the actual fix.

Fixing a plan is cheaper than fixing a pile of code. The “approved” step forces me to agree with the approach before the AI starts typing.

Step 3: Lightweight Multi-Agent Coding

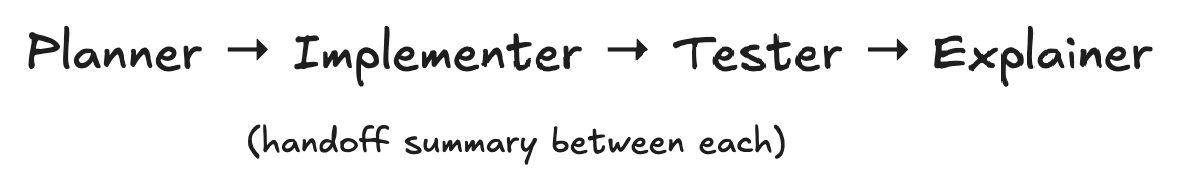

Once I got comfortable with planning before coding, I started using a simple trick that makes AI output more reliable: I split the work into roles.

This isn’t a complex ‘agent system9.’ Most of the time, it’s the same AI model, just prompted differently for each job.

Sometimes I use different models for different roles:

Claude or ChatGPT for the Planner role (where reasoning matters),

Then, a faster model for the Implementer role (where the task is already well-defined and speed matters more).

In Cursor, I can switch models mid-task, which makes this easy.

The four roles I use:

1. Planner: Breaks down the task into steps and calls out edge cases. (This is what we covered in Step 2.)

2. Implementer: Writes code strictly based on the approved plan. I prompt it with something like: “Follow the approved plan. Change only the files I list. Keep the change small. If something is unclear, ask before coding.”

3. Tester: Writes tests and edge cases. I prompt it with: “Write a unit test10 for the happy path11. Write at least two edge case tests12. If this were a bug fix, write a regression test that would fail before the fix.”

4. Explainer: Summarizes what changed and why. I prompt it with: “Summarize changes by file. Explain the logic in plain language. List what could break and how the tests cover it.”

Big prompts encourage messy answers.

When I ask the AI to plan, implement, test, and explain all at once, the output gets tangled. When I split roles, I get a checklist, then a small change, then tests, then an explanation. Each piece is easier to review.

Long chats also drift. After enough back-and-forth, the AI forgets earlier context or recycles bad ideas. Short, focused threads stay sharp.

Practical tip: summarise between steps.

When I finish one role, I ask for a short summary before moving to the next. Then I paste that summary into the next prompt. This keeps each step focused and prevents context from getting lost across a long conversation.

Step 4: Review the Output

AI-generated code needs extra review.

The model is confident even when it’s wrong, and subtle bugs hide easily in code that looks plausible. This is where I add a layer of automated review before merging anything.

One way to do this is with an AI code review tool like CodeRabbit, which integrates with GitHub and GitLab. When you open a pull request, it auto13matically reviews the diff14 and posts comments directly in the PR thread. This kind of tool catches issues that slip past manual reviews, especially when you’re tired or rushing.

A tool like CodeRabbit typically gives you two things:

First, a summary of what changed, often with a file-by-file walkthrough. This helps confirm the pull request matches your intent before looking at the details.

Second, line-by-line comments with suggestions. These often flag missing error handling, edge cases, potential security issues, and logic bugs like off-by-one errors. It can also run the code through linters and security analyzers during the review.

When you push more commits to the same PR, it reviews the new changes incrementally rather than repeating the entire review.

An example pull request flow

Here’s what a typical flow looks like:

Open a PR with a small, focused change.

The AI review tool automatically posts comments.

Read the comments, fix real issues, and reply to anything that’s noise or missing context.

Then do a final human pass before merging.

Not every comment requires action. Sort them into two buckets:

Must-fix: logic errors, missing error handling, security issues

Worth considering: style preferences, naming suggestions, alternative approaches

If you’re unsure whether something matters, ask yourself:

Would this likely cause a bug?

Or would this confuse someone reading the code later?

If yes to either, fix it or add a test.

AI review tools have the same limitations as other AI tools.

They sometimes flag things that aren’t problems or suggest patterns that don’t match the codebase. The goal is to catch obvious problems early, not to treat every comment as a mandate.

Always do a final human pass before merging.

Step 5: Test the Change

Tests are part of the flow, not a later chore.

After any change that isn’t small, I ask for tests immediately. I don’t wait until the feature is complete. Tests serve both as verification and as documentation. If the AI can’t write a sensible test for the code it just produced, that’s often a sign the code itself is unclear…

I request different tests depending on the situation.

For new functions, I ask for unit tests that cover the happy path and edge cases. When I used AI to build a React component in a stack I barely knew, my immediate follow-up was, “Now write unit tests for this component.” The tests showed me what the component was supposed to do and how it handled different inputs.

For bug fixes, I ask for a regression test that would have failed before the fix. This proves the fix works and helps prevent the bug from returning later. For changes that touch multiple components or an endpoint, I ask for one minimal integration or end-to-end test15.

I paste a short feature description and ask for a realistic user flow and a few edge cases.

Prompt templates I reuse

For unit tests:

Write unit tests for this function.

Cover the happy path and at least two edge cases.For regression tests:

Write a regression test for this bug.

The test should fail before the fix and pass after.For integration or end-to-end tests:

Write a minimal integration test for this feature.

Include one realistic user flow and a few edge cases.For reviewing existing tests:

Review these tests.

Are there obvious edge cases missing or any weak assertions?When I first started using AI for code, I would generate a function and move on.

Tests came later, if at all. Bugs shipped. And I didn’t always understand what the code was doing. Now I ask for tests right after the code. Reading the test often teaches me more than reading the function. It shows the inputs, the expected outputs, and the edge cases the code is supposed to handle.

If the generated test doesn’t make sense, I treat that as a signal. Either the code is unclear, or my prompt was incomplete. Either way, I go back before moving forward.

Step 6: Debug and Iterate

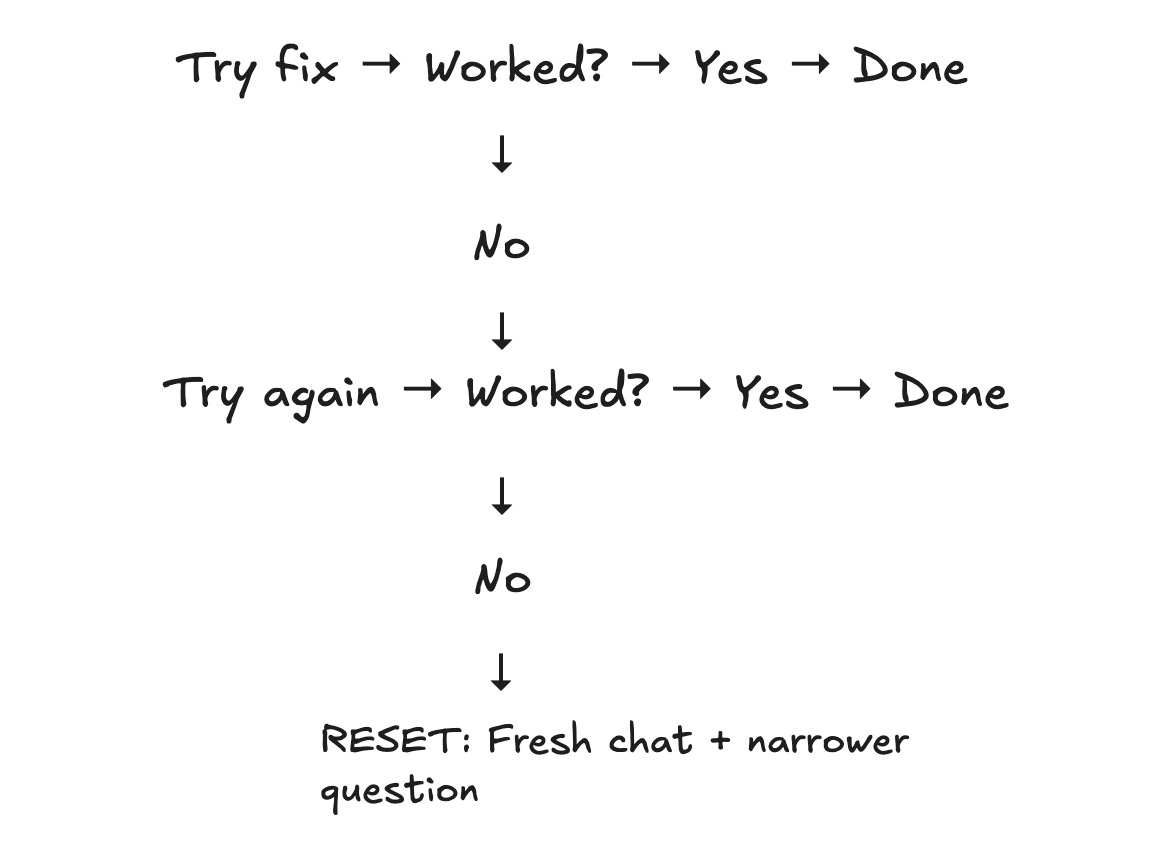

When something breaks… I don’t just paste an error and hope.

I give the model the same information I’d give a colleague: the error, the function, and enough context to reason through the problem.

A single error line is rarely enough. The model needs more than that to produce a useful diagnosis.

Here is what I include:

Error message or stack trace.

Function where the error occurs.

Relevant surrounding code or types.

What I expected to happen and what actually happened.

I avoid pasting only the error with no code, dumping an entire file without pointing to the relevant section, or just saying “it doesn’t work” without describing the failure.

The prompt I use for debugging (I usually ask for both the explanation and the fix in one request):

Here is the function and the error message.

Explain why this is happening.

Then rewrite the function using best practices, while keeping it efficient and readable.Asking for both gives me a diagnosis and a fix in one shot. It also helps me learn what went wrong, not just how to patch it.

If a fix doesn’t work and I keep saying “try again” in the same thread, the suggestions usually get worse. The model circles the same wrong idea with slightly different words.

My rule: if I’ve asked twice and the answers are getting repetitive or worse, I stop.

I start a fresh chat, restate the problem with better context, and narrow the question.

For example, instead of “fix this function,” I ask, “under what conditions could this variable be null here?” Fresh context plus a smaller question beats a tired thread most of the time.

Sometimes I realize I don’t understand the problem well enough to evaluate the fix. When that happens, I stop asking for code and start asking for an explanation:

Do not fix anything yet.

Explain what this function does, step by step.

Then list the most likely failure cases.Once I understand the logic, I go back to asking for a targeted fix.

This avoids the loop of accepting fixes I don’t understand and hoping one of them works.

Bet you didn’t know…

CodeRabbit CLI brings instant code reviews directly to your terminal, seamlessly integrating with Claude Code, Cursor CLI, and other AI coding agents. While they generate code, CodeRabbit ensures it’s production-ready - catching bugs, security issues, and AI hallucinations before they hit your codebase.

Common Failure Modes and Guardrails

After enough cycles, I started noticing the same failures repeating.

Here’s a short checklist I keep in mind:

Context drift in long chats

Long conversations cause the model to forget earlier decisions.

The fix: keep conversations short and scoped. One chat for design, one for part A, one for part B. When a thread feels messy, ask the model to summarize where you are, then start a fresh chat with that summary at the top.

Wrong API or version

Models are trained on data up to a certain point.

They sometimes write code for an older version of a library or generate methods that don’t exist. For anything new or fast-moving, I assume the suggestion might be wrong and verify against official docs. I also ask the model to state its assumptions: “Which version are you assuming?”

If the answer doesn’t match my setup, I rewrite it myself.

Off-rails debugging loops

Once a model gets stuck on a bad idea, it tends to dig deeper. It proposes variations of the same broken fix, sometimes reintroducing bugs from earlier attempts.

Code quality drift

AI rarely produces well-structured code by default.

It’s good at “something that runs,” less good at “something I’ll want to maintain in three months.”

I fix this by baking quality into the request: ask for tests, ask for a summary of what changed and why, and nudge toward structure (“refactor this into smaller functions,” “follow the pattern in file X”).

Over-reliance

This one has nothing to do with the model and everything to do with me.

If I let AI handle every decision, my own instincts start to dull. I push back by keeping important decisions human-owned, occasionally doing small tasks without AI, and asking the model to teach as well as do: explain its reasoning, compare approaches, and talk through trade-offs.

The goal is not just “ship faster” but “ship faster and understand what I shipped.”

Closing Thoughts

The workflow I use comes back to a simple loop:

Context → Plan → Code → Review → Test → IterateI give the model enough context to see the real problem.

I ask it to plan before writing code.

I generate and edit in small steps.

I review the output, often with AI-assisted tools.

I ask for tests right away.

And when something breaks, I debug, refine, and repeat until it works.

Tools and models will change. Pricing will change. New products will appear. What survives is your method: how you give context, how you break work into steps, when to use a model, and when to rely on yourself.

If this newsletter did its job, you now have a clearer picture of what coding with AI looks like in practice.

Some days it’s a sprint… Some days it’s a wrestling match. But it has changed how I work. I ship features I wouldn’t have attempted before, and I feel less stuck when learning a new stack or working through an unfamiliar codebase.

The goal is not just to ship faster, but to ship faster and understand what I shipped.

Anyway, if you want to catch bugs, security flaws, and performance issues as you write code… try CodeRabbit.

It brings real-time, AI code reviews straight into VS Code, Cursor, and Windsurf.

I launched Design, Build, Scale (newsletter series exclusive to PAID subscribers).

When you upgrade, you’ll get:

High-level architecture of real-world systems.

Deep dive into how popular real-world systems actually work.

How real-world systems handle scale, reliability, and performance.

10x the results you currently get with 1/10th of your time, energy, and effort.

👉 CLICK HERE TO ACCESS DESIGN, BUILD, SCALE!

🚨 Guest Authors Wanted: System Design & AI Engineering

You’ll get exposure to 200,000+ tech audience.

Along with hands-on support throughout the review & editing process.

Reply to this email with links to your prior work and a brief note on topics you’d like to write about.

Want to reach 200K+ tech professionals at scale? 📰

If your company wants to reach 200K+ tech professionals, advertise with me.

Thank you for supporting this newsletter.

You are now 200,001+ readers strong, very close to 201k. Let’s try to get 201k readers by 5 February. Consider sharing this post with your friends and get rewards.

Y’all are the best.

When AI generates plausible-sounding but incorrect information, like referencing a function or API that doesn’t exist. This is called hallucination.

A way to propose code changes in Git-based workflows. You create a PR to ask others to review and merge your changes into the main codebase.

Unusual or extreme inputs that might break your code, like empty strings, very large numbers, or null values.

Restructuring existing code without changing its behavior, usually to improve readability or maintainability.

A one-shot prompt is when you give an AI a single example of what you want, and it uses that one example to figure out how to respond to a new request.

A file in a project’s root directory that explains what the project does and how to use it.

Files that store project rules and constraints for AI tools. Some tools, like Claude Code, automatically look for these files.

A list of function calls that shows where an error occurred, helping you trace the path the program took before crashing.

An agent system is an AI setup where the model can plan, make decisions, and take actions - often using tools or other AIs - to achieve a goal with minimal human input.

A test that checks a single function or component in isolation.

The expected, error-free flow through a feature when everything goes right.

A test designed to catch bugs that reappear after being fixed. It should fail before the fix and pass after.

Tools that analyze code for potential errors, style issues, and suspicious patterns without running the code

A comparison showing what changed between two versions of code.

Tests that check how multiple parts of a system work together, or simulate a complete user flow.

Thank you. Loved every bit of this post.