How ChatGPT's New Marketplace Actually Works

#116: Apps in ChatGPT (Turning Conversations Into Interactive Workflows)

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

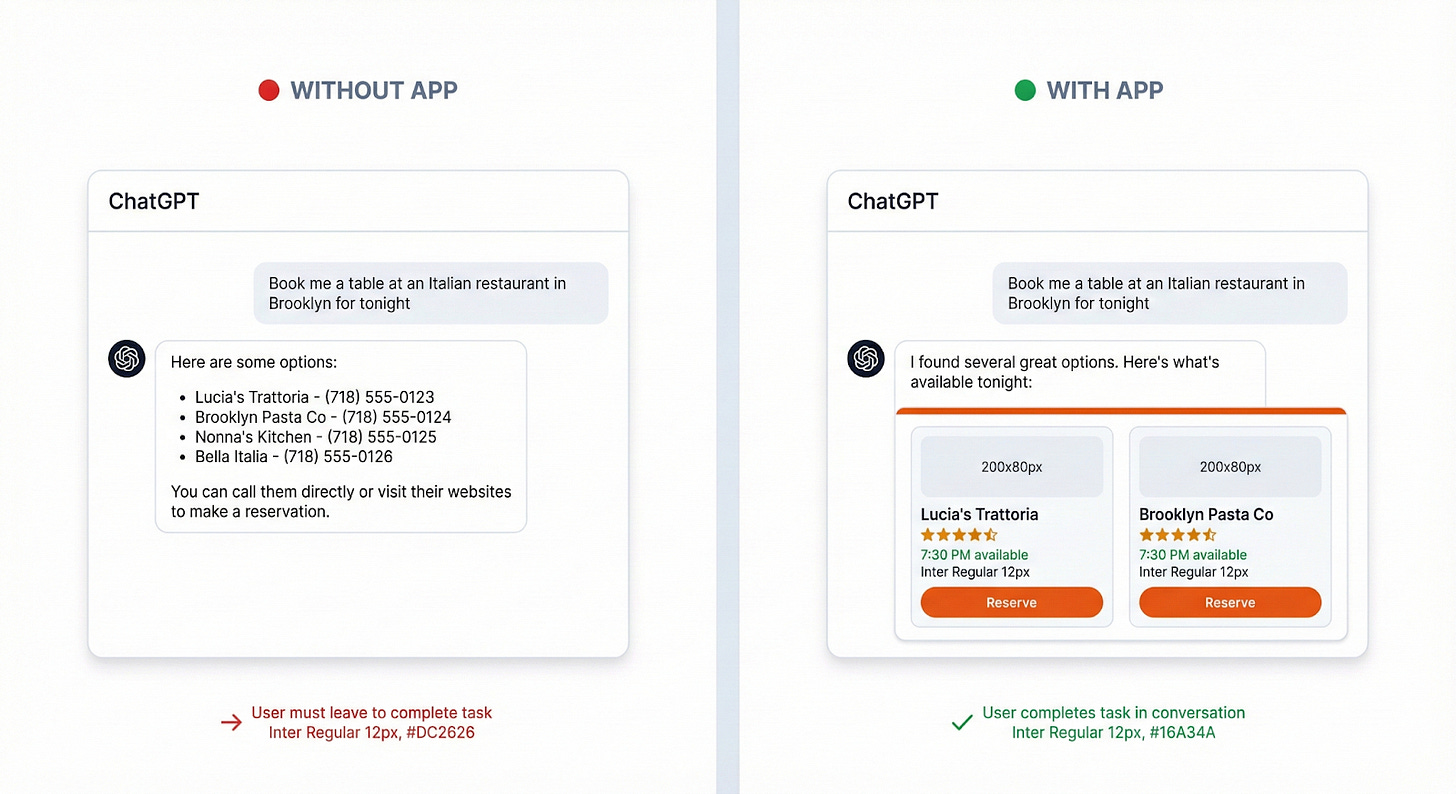

You’ve probably asked ChatGPT to help you book a flight or find a restaurant at some point.

It gives you a helpful list: airline breakdowns, price ranges, maybe some tips on timing. Then, you leave ChatGPT, open a travel website, and start your search from scratch.

The conversation helped you think, but it didn’t actually do anything…

Now imagine you say, “Find me a flight to Tokyo under $500,” and an interactive widget appears inside the chat. You browse options, compare prices, select your seat, and book, all without leaving the conversation.

That’s ChatGPT Apps.

Instead of responding with text and sending you elsewhere, ChatGPT can now surface interactive widgets from third-party apps directly in your conversation. OpenAI opened the app store for submissions on 17 December 2025, and with 800 million weekly active users, this may be the next great distribution wave for developers.

But how does it actually work?

How does a message like “find me a hotel” turn into an interactive booking widget?

In this newsletter, I’ll break down the architecture behind ChatGPT Apps, walk through how tool calls1 and widgets2 work together, and cover everything you need to know to build your own.

We’ll follow one example throughout: building a restaurant finder.

Onward.

Blitzy: First Autonomous Software Development Platform (Partner)

Blitzy is the first autonomous software development platform with infinite code context, enabling Fortune 500 companies to ship 5x faster.

Large enterprises are adopting Blitzy at the beginning of every sprint. While individual developer tools like co-pilots struggle with context and only autocomplete code, Blitzy is engineered specifically for enterprise-scale codebases: clearing years of tech debt and executing large-scale refactors or new feature additions in weeks, not quarters.

The Blitzy Edge:

Infinite Code Context - Ingest millions of lines of code, mapping every line-level dependency.

Agent Orchestration - 3,000+ cooperative agents autonomously plan, build, and validate production-ready code using spec and test-driven development at the speed of compute.

End Result - Over 80% of the work delivered autonomously, 500% faster.

The future of autonomous software development is here:

I want to introduce Colin Matthews as a guest author.

He’s the founder of Chippy.build, an enterprise prototyping and observability platform for ChatGPT Apps. He’s also a popular Maven instructor and former healthtech product manager.

Find him on:

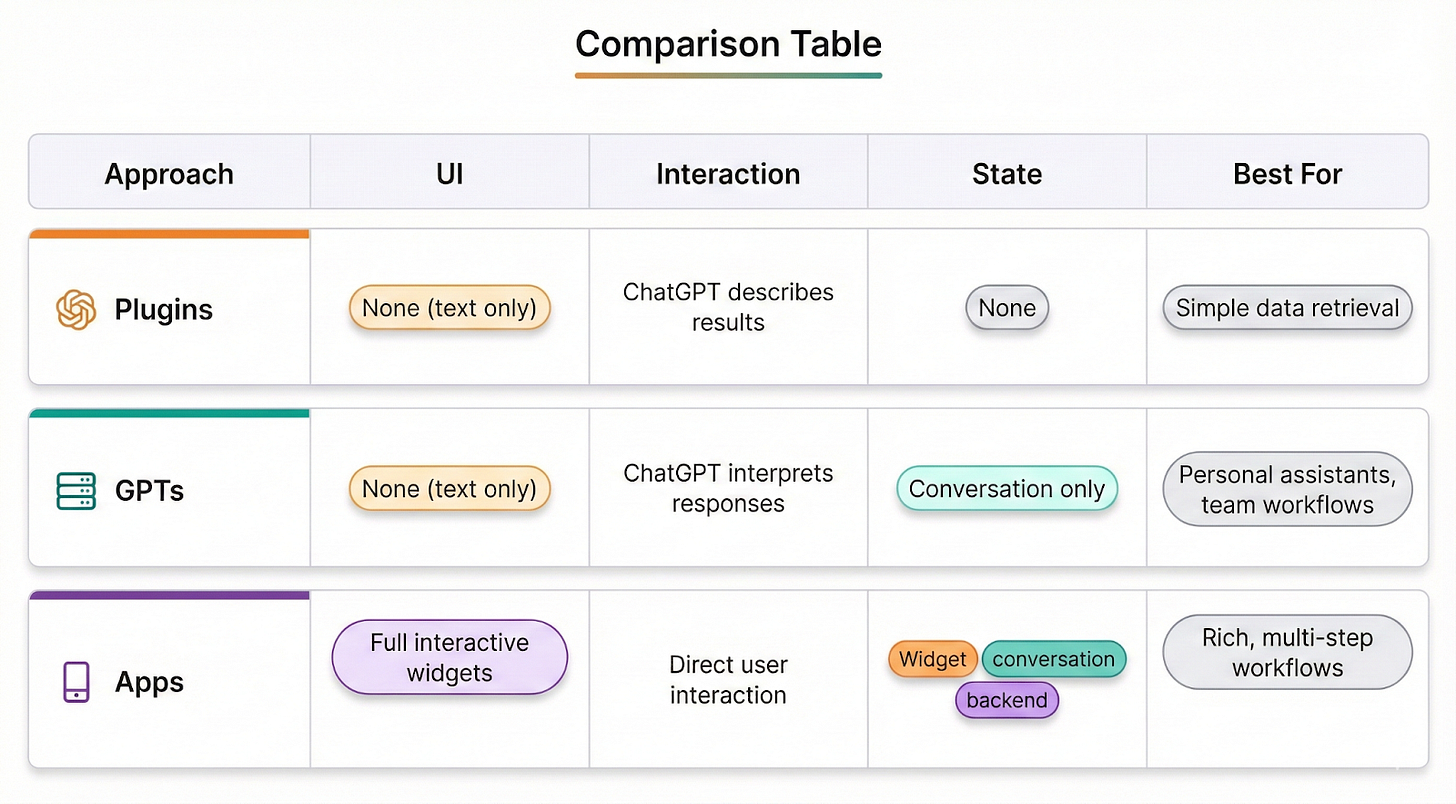

How Is This Different From Plugins?

If you’ve been following OpenAI for a while, you might think, “Wait, didn’t they already try this with Plugins?”

ChatGPT Plugins (launched March 2023, deprecated April 2024) were essentially API wrappers. You’d describe your API endpoints, and ChatGPT would call them and return text. The problem was that everything came back as text that ChatGPT had to interpret and re-present to the user3. There was no native UI, no interactivity, and no way to create rich experiences.

GPTs are similar.

They allow users to upload content and shape their conversations, but are difficult to share broadly and don’t give brands control over how they’ll appear in chats.

ChatGPT Apps take a fundamentally different approach.

Instead of just calling APIs and returning text, Apps can render full interactive widgets directly in the conversation. You can show a map, display a booking form, or let users interact with a spreadsheet.

Here’s how the three approaches compare:

The key insight is that Apps aren’t just “GPTs with UI”; they’re a different architecture entirely.

The widget runs in a sandboxed iframe with its own state, its own event handling, and direct communication with your backend4. ChatGPT orchestrates when to show your app, but once it’s rendered, users interact with your UI directly.

What Is a ChatGPT App?

Here’s the simplest way to think about it: a chatbot talks, but an app does.

Ask ChatGPT to book a restaurant, and normally, it explains how. It lists options, gives links, and tells you what to search for. Helpful, but nothing actually changes in the world.

Now ask ChatGPT with a restaurant app installed, and something different happens.

An interactive widget appears right in the chat. You can see real availability, browse the menu, pick a time, and confirm your reservation. When you’re done, you have an actual booking, not just information about how to make one.

Here’s exactly what that would look like:

The launch partners tell you a lot about where OpenAI sees this going: Booking.com, Canva, Coursera, Expedia, Figma, Spotify, and Zillow.

Users install apps through: Settings > Apps & Connectors.

Once installed, ChatGPT can automatically surface your app based on conversation context, or users can tag it manually.

What Can You Build?

Before we get into the technical details, it’s worth thinking about what kinds of apps work well in this model.

ChatGPT apps should be quick and conversational. The goal is not to export your entire web app to ChatGPT. OpenAI says that apps should show, do, or know something that ChatGPT doesn’t. For example, ChatGPT can’t deliver groceries to your house, but the Instacart app with ChatGPT can.

Now let’s look at how this all works under the hood.

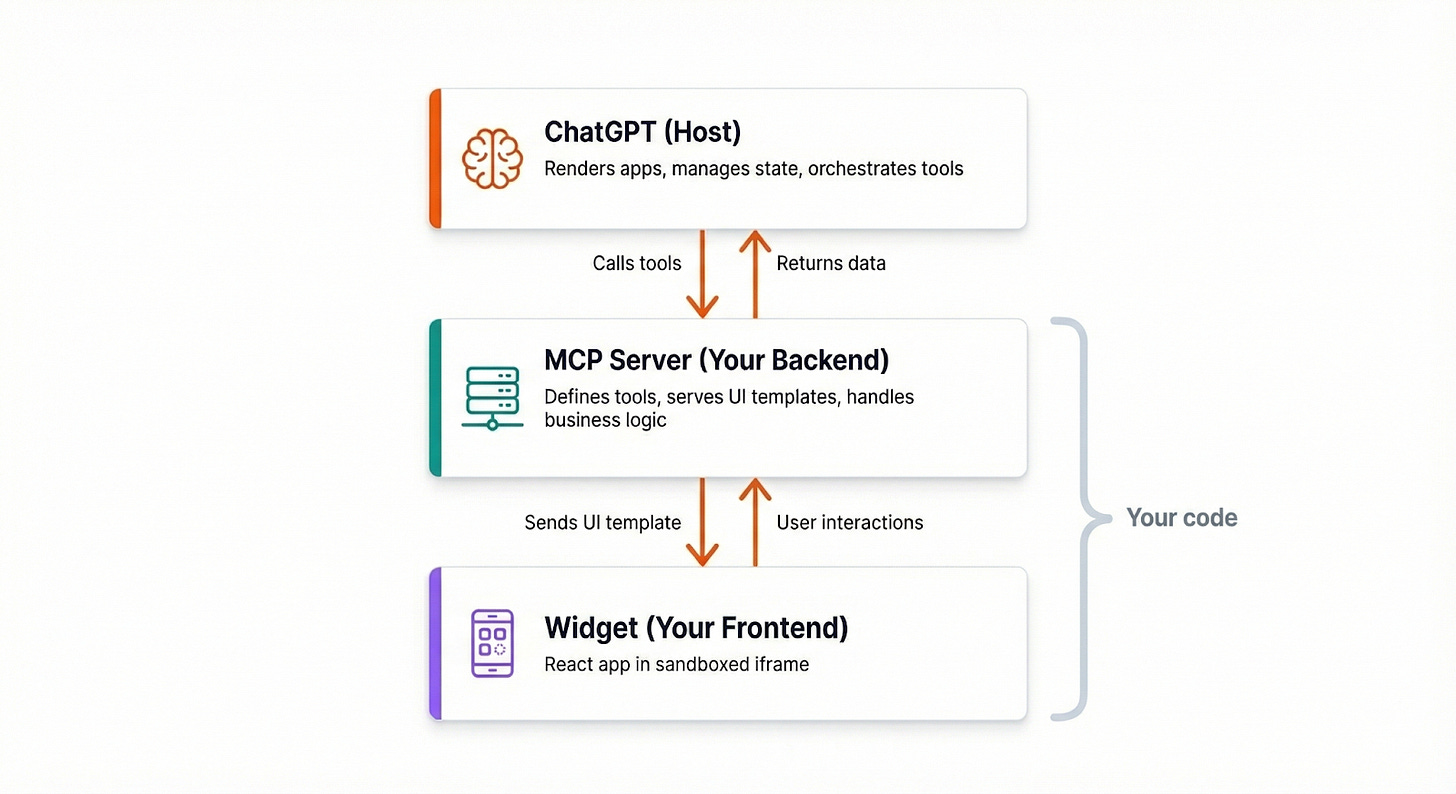

Every ChatGPT App is built from three parts that work together5:

The first is the MCP Server, which is your backend. It tells ChatGPT what your app can do by defining “tools” (functions the model can call) and “resources” (UI templates to render).

MCP stands for Model Context Protocol, an open standard that Anthropic created and OpenAI has now adopted.

The second component is the Widget, which is your frontend. It’s HTML that runs on ChatGPT in a sandboxed iframe.

The third is ChatGPT itself, which acts as the host. It decides when to call your tools, renders your widgets, and manages the conversation state.

Let’s look at each component in detail:

The MCP Server

The MCP Server is your backend—it’s where you define what your app can actually do.

It exposes two main things to ChatGPT: tools and resources.

Tools are actions that ChatGPT can call.

Each tool has a name (like search_restaurants), a description that helps ChatGPT decide when to use it, an input schema defining which parameters are required, and an output template specifying which UI resource to render the results in.

Resources are UI templates that ChatGPT renders when tools return data.

They’re served as HTML bundles (typically React apps compiled to a single file) and rendered inside a sandboxed iframe.

Here’s what a tool definition might look like for our restaurant finder:

Tool: search_restaurants

Description: “Find restaurants by location and cuisine type”

Inputs: location (required), cuisine (optional), price_range (optional)

Output: → ui://widget/restaurant-list.htmlThe description is especially important.

ChatGPT uses it to decide whether your tool is relevant to the user’s request. If your description is vague—like “do restaurant stuff”—ChatGPT won’t know when to invoke it. Be specific about what the tool does and when it should be used.

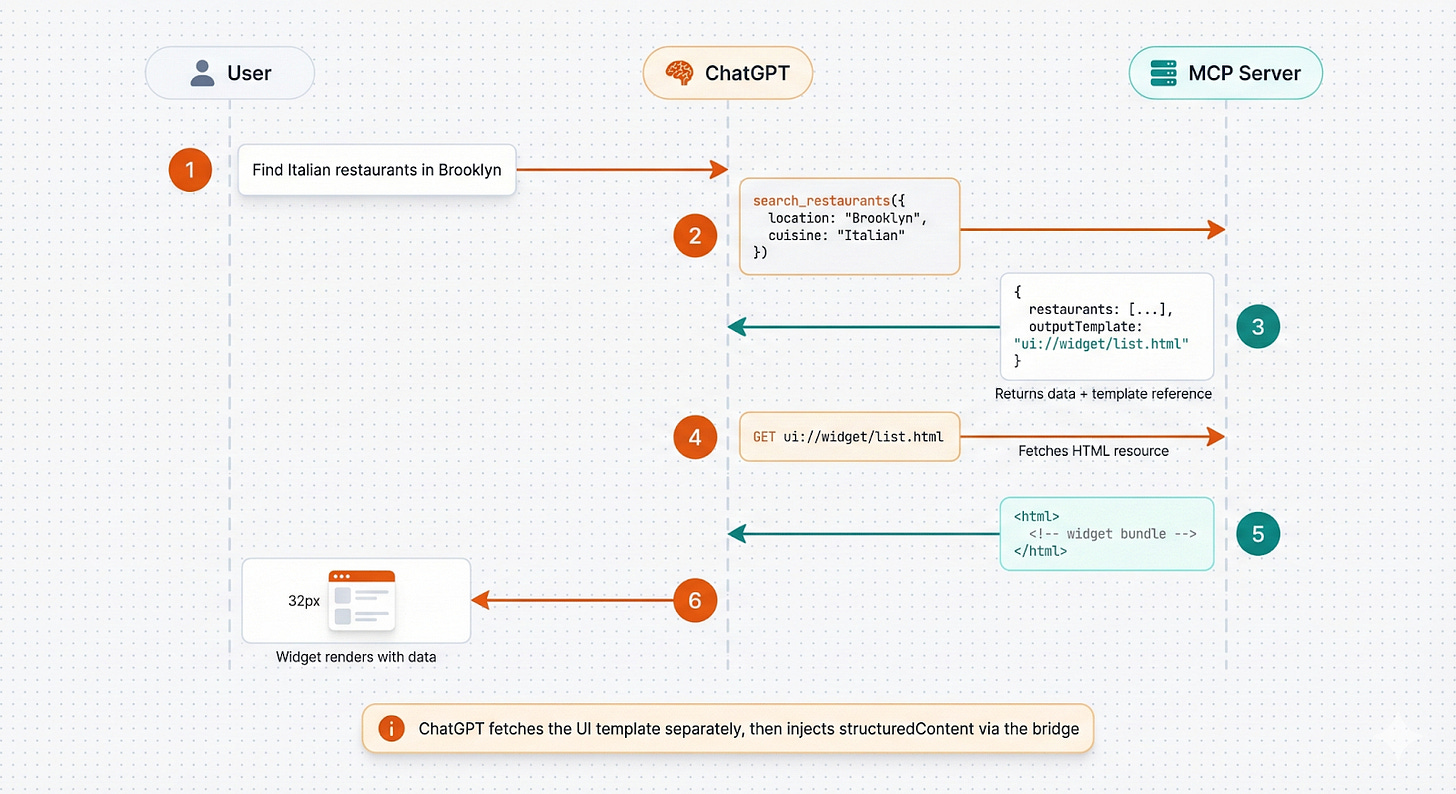

Let’s trace what happens when you tell ChatGPT, “Find me Italian restaurants in Brooklyn”.

Understanding this flow is key to building apps that work well.

First, ChatGPT checks the available tools from all installed apps.

It sees your search_restaurants tool with the description “Search for restaurants by location and cuisine type”. Based on the user’s message, it decides this tool is relevant.

Next, ChatGPT constructs a tool call:

{

“name”: “search_restaurants”,

“parameters”: {

“location”: “Brooklyn”,

“cuisine”: “Italian”

}

}Your MCP server receives this request, validates the parameters, queries your database (or an external API such as Yelp), and returns the results.

This includes a reference to your UI template if you have one.

return {

content: [

{ type: “text”, text: “Found 12 Italian restaurants in Brooklyn” }

],

structuredContent: {

restaurants: results

},

_meta: {

“openai/outputTemplate”: “ui://widget/restaurant-list.html”

}

};The

contentfield is for ChatGPT. It’s a text summary, so the model knows what happened and can respond intelligently.The

structuredContentfield is for your widget, containing the raw data your UI will display.And the

outputTemplatein_metatells ChatGPT to fetch and render your widget HTML.

Finally, ChatGPT fetches your HTML bundle, renders it in a sandboxed iframe, and injects your structuredContent via a JavaScript bridge. The user sees an interactive list of restaurants right in their chat.

The Widget

The Widget is your frontend widget.

When your widget loads, ChatGPT injects an window.openai object6 that gives you access to data and methods for interacting with the system.

Here’s what you can do with window.openai:

Read data:

toolOutput— The data returned from your tool calltoolInput— The parameters that were passed to your toolwidgetState— Any persisted UI statetheme— Whether the user is in light or dark modelocale— The user’s locale (e.g., “en-US”)

Take actions:

callTool()— Call another MCP tool directlysetWidgetState()— Persist UI statesendFollowUpMessage()— Send a message back to ChatGPTrequestDisplayMode()— Switch between inline, full screen, or picture-in-pictureopenExternal()— Open an external URL

This is what makes Apps fundamentally different from Plugins.

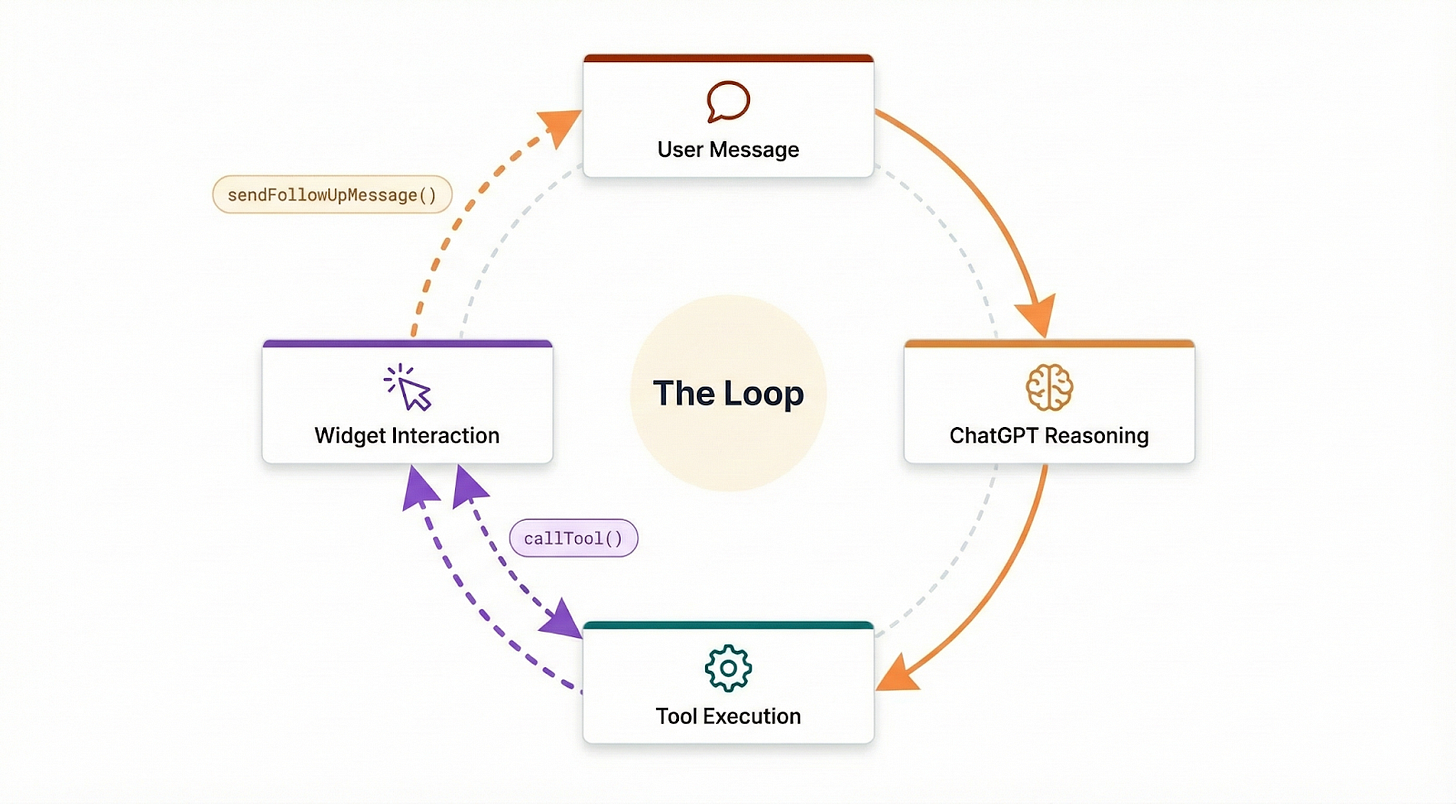

Your widget can trigger new tool calls, save state, and continue the conversation. Users interact directly with your UI, not through ChatGPT’s text interface. When they click on a restaurant to see more details, you have two options for handling that interaction.

The first option is a direct tool call.

Your widget can call tools directly using window.openai.callTool(), which bypasses the model entirely. Your widget requests restaurant details, your server returns the data, and the widget updates immediately. This is fast and efficient for straightforward data fetching.

The second option is a follow-up message.

Your widget can send a follow-up window.openai.sendFollowUpMessage(), which puts the model back in the loop. ChatGPT sees the message, decides what to do next, and might call additional tools or ask clarifying questions.

// Direct tool call (model not involved)

const details = await window.openai.callTool(

‘get_restaurant_details’,

{ id: restaurant.id }

);

// Follow-up message (model decides next step)

await window.openai.sendFollowUpMessage({

prompt: `I want to book ${restaurant.name} for 4 people`

});This creates a continuous loop that makes the whole experience feel seamless:

The user speaks, ChatGPT calls a tool, the widget renders, the user interacts with the widget, the widget either calls another tool or sends a message, and the cycle continues.

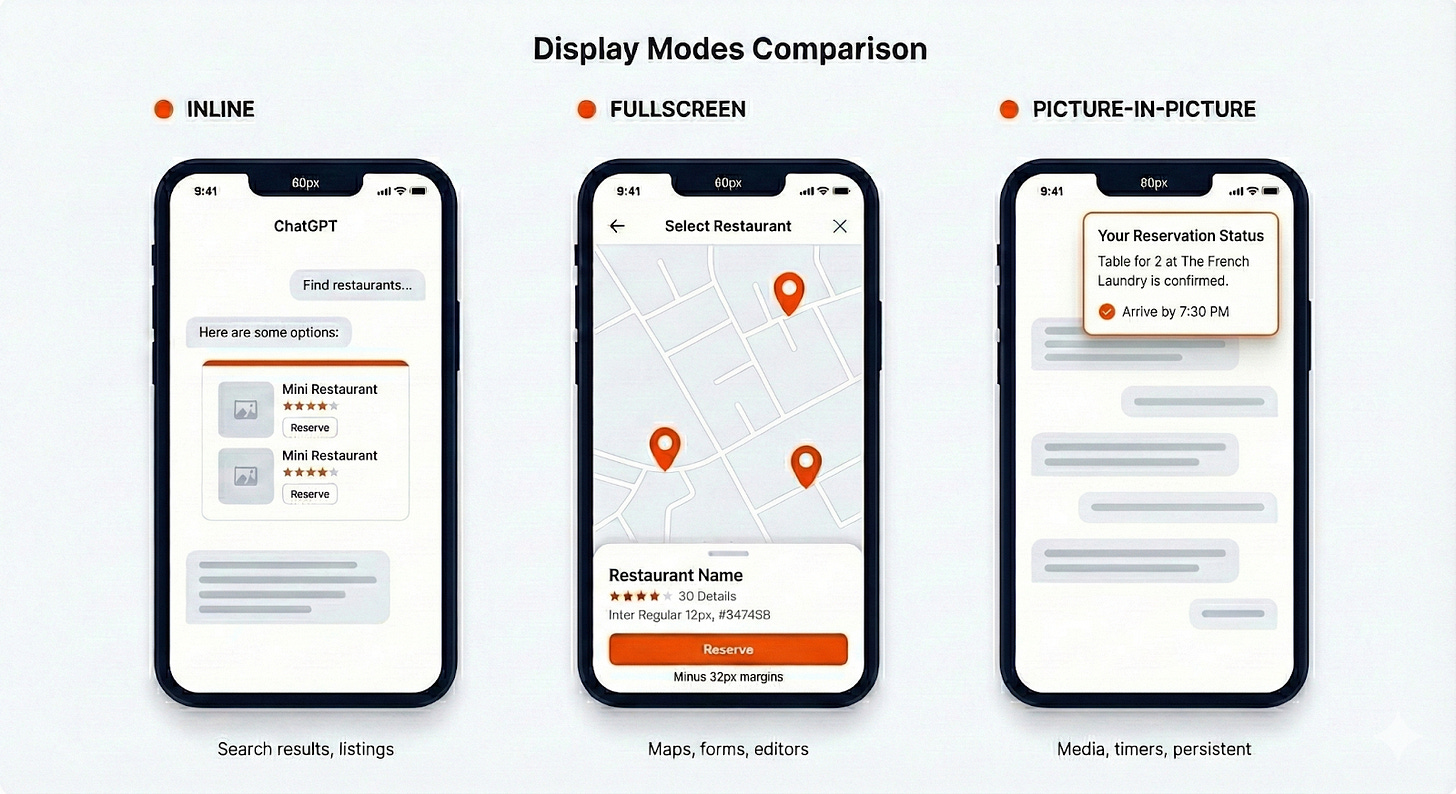

Widgets can appear in three different formats depending on what makes sense for your app.

Inline widgets embed directly in the conversation flow. This is the default for all apps, and it works well for things like listings, search results, or quick selections.

Fullscreen mode takes over the entire viewport. This is better for maps, dashboards, or complex workflows where users need more space to work.

Picture-in-picture mode floats the widget while the user continues chatting. This is great for music players, timers, or other persistent tools that the user might want to keep visible while doing other things.

window.openai.requestDisplayMode({ mode: “fullscreen” });

window.openai.requestDisplayMode({ mode: “pip” });One constraint to keep in mind: you can only show one widget per message.

If someone asks ChatGPT to “book a restaurant and order an Uber,” it will show one app at a time. Users work through these requests sequentially.

Security

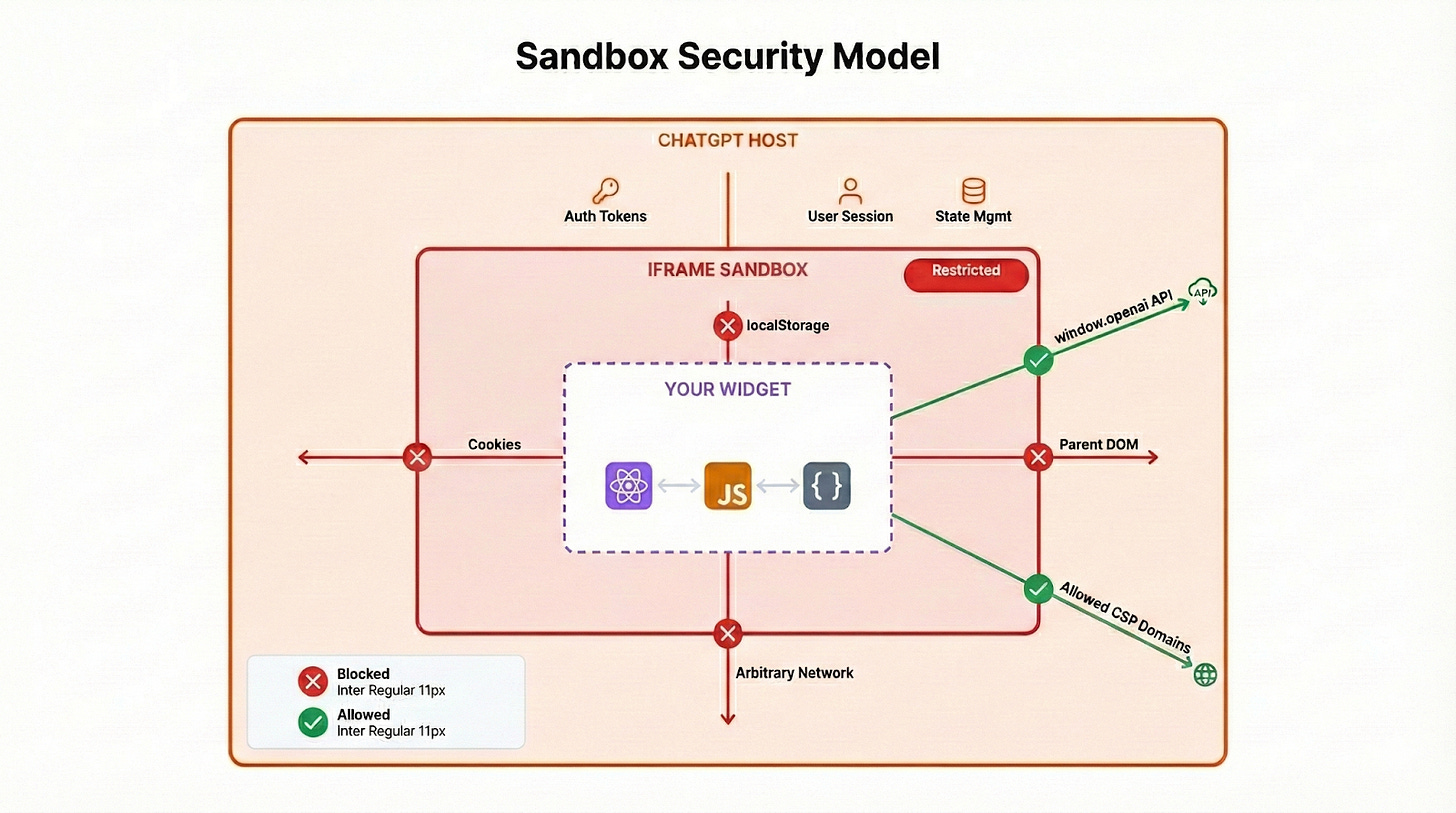

Now that we understand how the pieces fit together, let’s talk about security.

With four parties involved (ChatGPT, your MCP server, your widget, and external APIs), it’s important to understand where the trust boundaries lie.

ChatGPT ↔ MCP Server:

ChatGPT calls your MCP server over HTTPS. Your server should validate that requests are actually coming from ChatGPT. ChatGPT trusts your server to return valid tool responses and UI resources.

ChatGPT ↔ Widget:

The widget runs in a heavily sandboxed iframe. ChatGPT injects the window.openai bridge, but the widget cannot access ChatGPT’s DOM, cookies, or any data from other apps. This is the strictest boundary.

Widget ↔ External APIs:

Your widget can only make network requests to domains you’ve explicitly declared in your Content Security Policy7 (CSP) configuration. All other requests are blocked.

App ↔ App Isolation:

Each app’s widget runs in its own isolated sandbox. Apps cannot access each other’s data, state, or DOM. Even if a malicious app tried to extract data from another app, the browser’s same-origin policy prevents it.

Your widget runs under strict restrictions. It cannot:

Access cookies (it’s on a sandbox origin, not your domain)

Use localStorage or sessionStorage

Access the parent DOM (ChatGPT’s interface)

Submit forms directly (use

callTool()instead)Open popups (use

openExternal()instead)Make network requests except for declared CSP domains

It can:

Execute JavaScript normally

Fetch from CSP-allowed domains

Communicate through the

window.openaibridgeStore UI state via

setWidgetState()

You declare your allowed connections in your tool’s _meta:

_meta: {

“openai/widgetCSP”: {

“connect_domains”: [”api.yourservice.com”],

“resource_domains”: [”cdn.yourservice.com”],

“frame_domains”: [] // Nested iframes trigger stricter review

}

}The key principle: external API calls should go through your MCP server, not the widget.

Let your widget handle the UI and let your server handle the business logic and sensitive operations.