Distributed Systems – A Deep Dive

#105: Understanding Distributed Systems

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Distributed systems aren’t just a concept; they’re the invisible machinery holding our digital world together.

Every time you send a message, book a taxi, or stream a song, dozens of nodes across the world work together to make it look simple. But simplicity on the surface hides chaos underneath.

We’ll see how these systems serve millions globally while maintaining control over the chaos.

But first, let’s understand why we need distributed systems…

The AI Agent for production-grade codebases (sponsor)

Augment Code’s powerful AI coding agent and industry-leading context engine meet professional software developers exactly where they are, delivering production-grade features and deep context into even the largest and gnarliest codebases.

With Augment Code you can:

Index and navigate millions of lines of code

Get instant answers about any part of your codebase

Automate processes across your entire development stack

👉 BUILD WITH AI AGENT THAT GETS YOU, YOUR TEAM, AND YOUR CODEBASE

I want to introduce Sahil Sarwar as a guest author.

He’s a software engineer at Confluent, passionate about distributed systems, system internals, and the philosophy behind designing large-scale systems.

Connect with him if you’re interested in deep dives into distributed systems, infrastructure, and the mindset behind technical design.

Why Distributed Systems?

Traditionally, software systems ran on a single machine.

But as the internet became popular, we realized a single machine might be insufficient at scale. That’s how the idea of vertical and horizontal scaling came in…

1 Vertical Scaling

A simple way to scale is by adding:

more CPU,

more memory,

faster processors.

However, it’s impossible to scale vertically forever because of hardware limitations & cost effectiveness.

2 Horizontal Scaling

Instead of relying on one powerful server,

“What if many small servers shared the work?”

And those servers coordinate to act as one unit. That’s the key idea behind a DISTRIBUTED SYSTEM.

What are Distributed Systems?

When you hear “distributed systems”, you might think of buzzwords like clusters, microservices, or Kubernetes…

But the core idea is actually simple:

A distributed system is a group of independent servers that work together and appear to the user as one system.

Each server has its own CPU, memory, and processes.

They communicate over a network to achieve one shared goal. There’s no shared RAM, no shared global clock, and no single machine that “knows everything.”

These features define distributed systems:

No Shared Memory

Each node works independently and can’t directly read another machine’s variables.

All communication happens through messages sent over the network.

We need idempotency1, retry logic, and consensus algorithms2 to maintain system correctness even when messages are lost or fail.

No Global Clock

There is no universal time across machines.

Clocks drift, and network delays make timing unpredictable.

This makes it difficult to determine the exact order in which events occurred.

To solve this, we use logical time:

Lamport Clocks

If timestamp a is less than b, then event a happened before event b in logical order.

Vector Clocks

Extend Lamport clocks by tracking event counts from every node, allowing systems to detect concurrency and understand ordering across many processes.

Message Communication

Nodes communicate using protocols such as gRPC3, HTTP4, Kafka events5, and so on.

Messages may not arrive, may arrive late, may be duplicated, or may even arrive out of order.

A distributed system stays correct not because communication is perfect, but because it handles failures gracefully.

Let’s keep going…

Distributed Systems in Real Life

Distributed systems aren’t just theory - they’re everywhere, and in everything that we use:

Google Search: a massive network of crawlers, indexers, and ranking nodes running across many data centers.

Netflix: region-wide services for streaming, recommendations, authentication, video transcoding, and content delivery.

DynamoDB & Cassandra: distributed key–value stores that replicate data across nodes for availability and scale.

Kafka: distributed, fault-tolerant event log for asynchronous communication.

Stripe: event-driven architectures built on reliable messaging and idempotent operations.

Distributed vs Decentralized vs Parallel Systems

These three terms sound similar, but they describe different designs…

1 Distributed Systems

A distributed system is a group of independent nodes that work together to present themselves as a single, logical system.

Examples:

Google Spanner (globally distributed database)

Apache Kafka (distributed log system)

There is often a “leader or a control plane” responsible for managing consistency, replication, and communication between nodes.

2 Decentralized Systems

A decentralized system removes or minimizes the need for a single point of control.

Examples:

Bitcoin and Ethereum (blockchain networks)

BitTorrent (peer-to-peer file sharing)

Each node operates more autonomously, and coordination occurs through peer-to-peer consensus, not central orchestration.

3 Parallel Systems

They run multiple computations simultaneously, but on a single machine or a tightly coupled cluster with shared memory.

They typically have:

One global clock,

A shared memory space.

Examples:

GPU workloads

Multithreaded programs

High-performance computing clusters

TL;DR

Distributed systems: loosely coupled, message-passing, reliability-oriented

Decentralized systems: trustless, peer-based, no central authority

Parallel systems: tightly coupled, shared memory, performance-oriented

If many machines need to work together, they must communicate and share state efficiently.

The next question then is:

“How do machines communicate effectively at scale?”

Communication in Distributed Systems

When machines communicate in a distributed system, all interactions occur over a network. And networks come with their own set of messy realities.

Onward.

1 Network Realities

By default, the network is unreliable… Messages can:

Be lost: never reach the destination

Be duplicated: delivered more than once

Be corrupted: bits flipped during transit

Arrive out of order: later messages come before earlier ones

Experience latency: unpredictable delays

Designing a distributed system is really about expecting the WORST and still making the system work.

As Murphy’s law states:

“If something can go wrong, it will go wrong.”

2 TCP: Reliability Layer

Distributed systems rely heavily on TCP6 because it provides:

Reliable delivery: data gets delivered reliably, or the sender is notified of failure

Ordering: packets arrive in the order they were sent

Error checking: corrupted packets are detected and retransmitted

TCP establishes this connection via a 3-way handshake:

SYN: Client says, “I want to connect.”

SYN-ACK: Server replies, “Got it, ready to proceed.”

ACK: Client confirms, “Great, let’s begin.”

3 TLS: Security Layer

You can consider TCP as a “mailman” and TLS7 as the envelope with a lock and signature. TLS ensures:

Encryption8: nobody can read the data

Authentication: you know who you’re talking to

Integrity: messages can’t be altered without detection

During the TLS handshake, both sides:

Choose cipher suites

Agree on the TLS version

Verify the server’s TLS certificate

Generate session keys for encrypted communication

Reliability loses its meaning if someone can intercept or tamper with the data. In modern systems, every RPC and network call should use TLS.

If servers spread worldwide, how do they find each other?

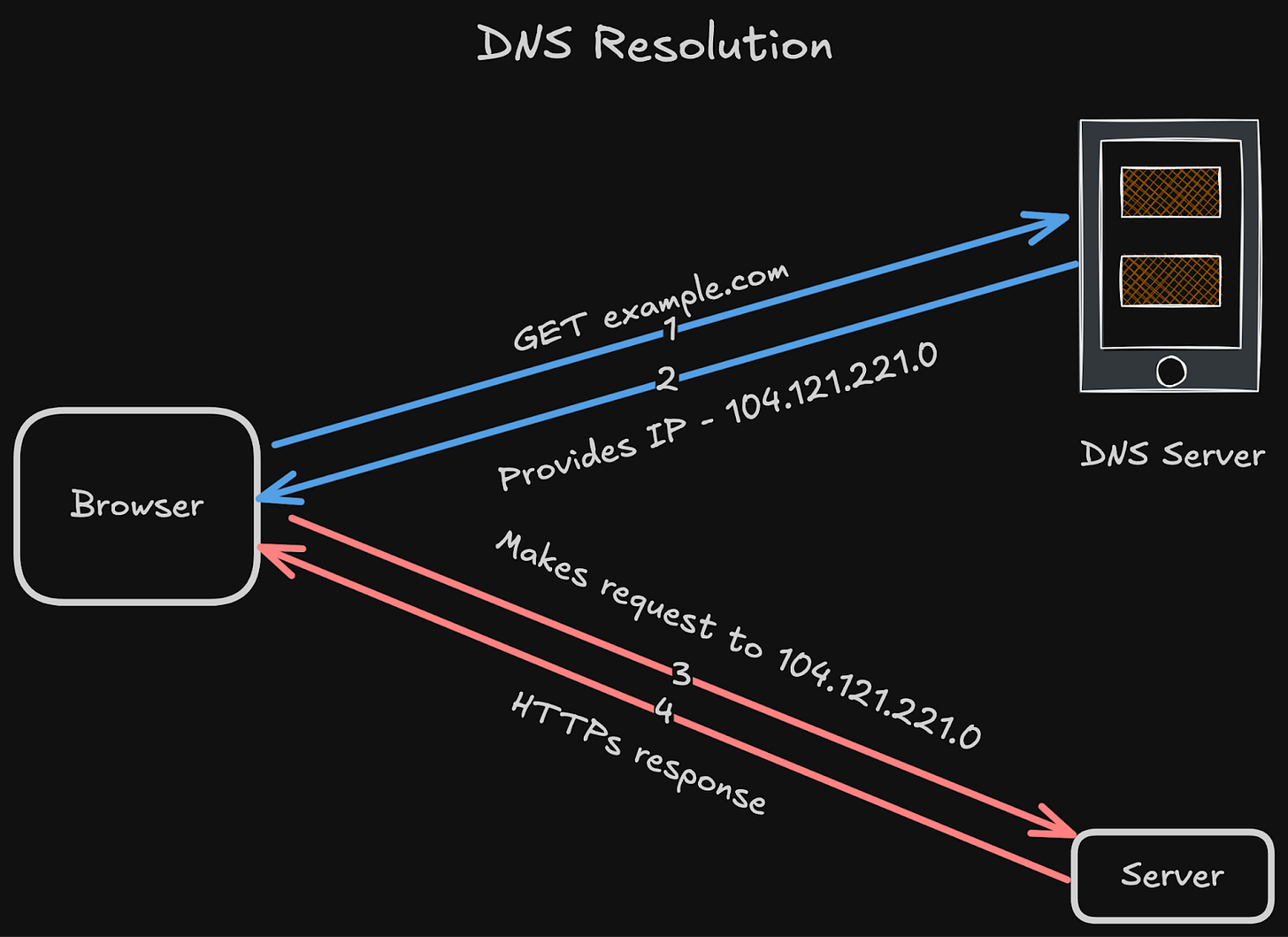

4 DNS: Finding the Right Node

That’s where DNS (Domain Name System) comes in:

It resolves human-readable names to IP addresses.

And acts as a basic service discovery9 mechanism.

In large distributed systems, DNS is usually layered with service registries or load balancers. But at the core, you always need a way to translate a name into a network endpoint.

Communication alone is not enough… For a distributed system to function as a single, coherent system, the nodes must also coordinate their actions.

And that brings us to the next major challenge: coordination.

Coordination Challenges in Distributed Systems

Once machines start working together, they need to stay in sync. Yet coordinating many nodes creates new problems.

Let’s look at the key challenges:

1 Failure Detection

Determining whether a machine has failed may seem simple… but it’s not.

“If a node doesn’t respond, is it dead, or just slow?”

Distributed systems usually detect failures using these two ways:

Heartbeat mechanism

Heartbeat messages are small signals that nodes send to each other to show they are still alive.

These messages serve as health checks, enabling each node to determine whether its peers are functioning properly or have failed.

Gossip protocol

Each node regularly sends a small “I am alive” message to others.

System considers the node dead if these messages stop for too long.

Like real gossip, nodes share what they know with others.

These techniques help to detect failures in a noisy, unreliable network.

But you’ve got to find a balance between speed and accuracy:

Check often → false positives (you think a node failed when it hasn’t)

Check slowly → system reacts late to real failures

If machines are spread around the world, it becomes hard to know which event happened first between two different servers.

So let’s read the solution to this problem:

2 Event Ordering and Timing

If we use time.Now() to decide “which event happened when,” we run into issues:

Each machine has its own local clock… and these clocks can drift10.

Because of this, it is almost impossible to keep all clocks perfectly in sync across many machines.

In distributed systems, we rarely care about the exact timestamp. What we really need to know is which event happened first.

To solve this, we use algorithms called “logical clocks”.

Lamport Clocks

Lamport clocks use a simple counter on each machine:

Each process starts with a counter at 0

For every local event, increase the counter:

LC = LC + 1When sending a message, attach the current counter value

When receiving a message, update the counter to:

LC = max(local LC, received LC) + 1

Example:

Consider two machines - M1 and M2.

M1 sends a message with

LC = 5M2 receives it when its own clock is

LC = 3So M2 updates its clock to

max(3, 5) + 1 = 6

From the above interactions:

Send event has LC = 5

Receive event has LC = 6

This keeps the correct order11: send < receive.

It tells you what happened before what… but not if two events were independent… so it cannot detect concurrency.

Let’s understand why:

M1 has

LC = 5and does event A →LC(A) = 6M2 has

LC = 2and does event B →LC(B) = 3

These two events are independent; there is no communication between the machines.

But Lamport clocks say 3 < 6, so it looks like B happened before A, even though they were concurrent. So Lamport clocks only show ordering, not concurrency.

Vector clocks fix this problem!

Vector Clocks

They extend the idea on which Lamport’s clocks are based:

“What if every machine knows every other machine’s order?”

If there are N machines, the vector keeps N entries, and each entry tracks that machine’s event count, M[i].

This means:

Every event carries a snapshot of what that machine knows about others’ state.

When a machine receives a message, it merges the knowledge using element-wise maximum.

This gives each machine a partial history of the entire system.

With vector clocks, a system can tell:

Which event happened first,

Whether two events happened at the same time (concurrently).

In a distributed system, we need a single source of truth for all operations… so it helps to have one machine act as the leader.

Let’s dive in!

3 Leader Election

The leader becomes the source of truth, and the other machines (followers) replicate its state.

But if all servers share the same design, how can we determine which server qualifies to become the “leader”?

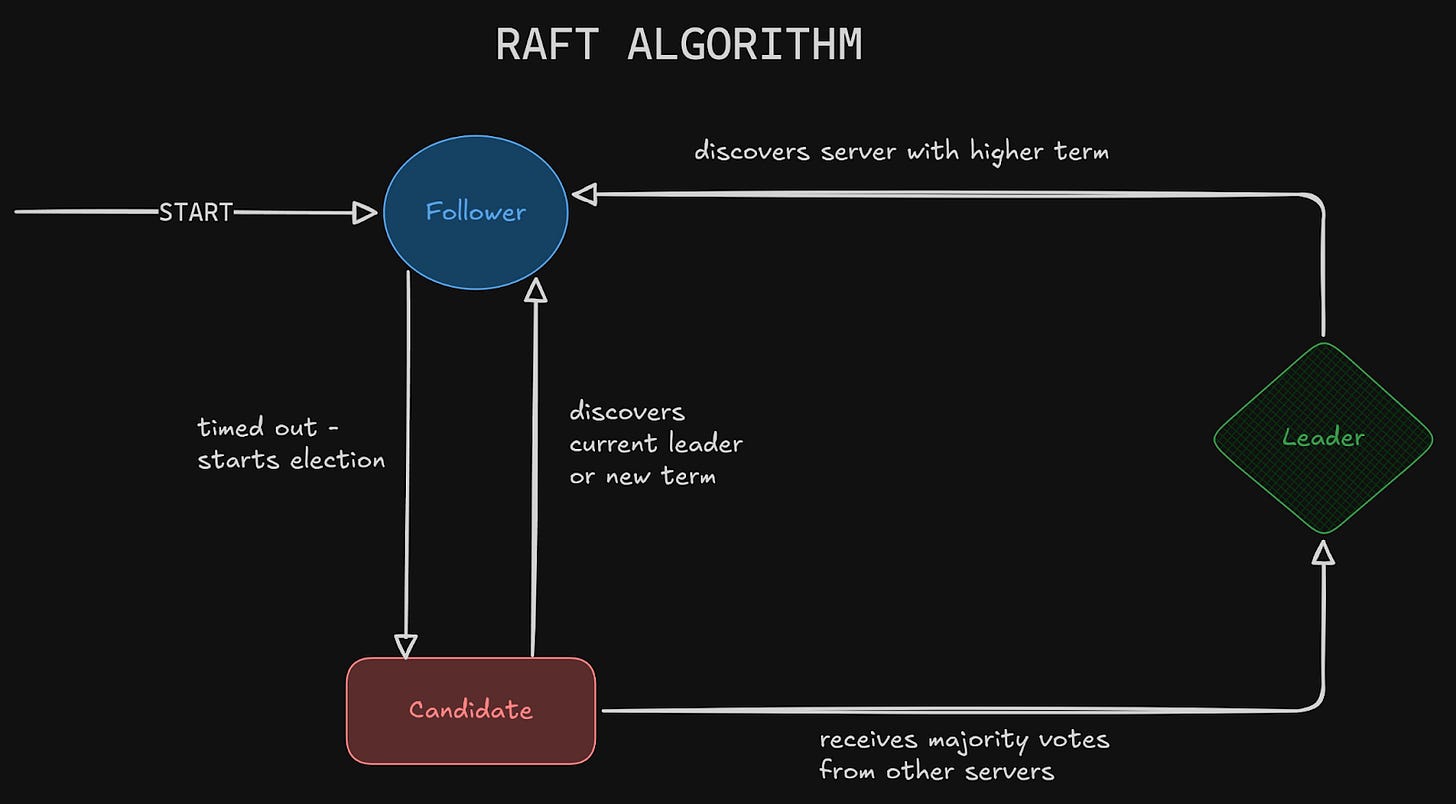

Algorithms like Raft12 solve this in a clean and predictable way:

All nodes start as followers.

If no leader is found, the followers enter a candidate state to become the leader.

Voting occurs, and the node that gets the most votes becomes the leader.

Once elected, the leader coordinates updates, and followers replicate its log.

Raft is popular because it’s simple, has well-defined states (follower, candidate, leader), and provides strong safety guarantees. It’s used in many distributed databases and consensus systems.

4 Data Replication and Consistency

Maintaining data consistency across many machines is one of the most challenging problems in distributed systems.

Because data is stored on different nodes, every write must be replicated to other nodes to ensure consistency.

But not all systems need the same level of strictness… different consistency models exist depending on what the application needs:

Linearizability

Every operation looks instant and globally ordered.

Readers always see the latest write.

This is the strictest model and is expensive at scale because every operation requires coordination across machines.

Plus, it often adds latency.

Sequential Consistency

Each node’s operations appear in order, but different nodes may see different global orders.

It's easier to achieve than linearizability.

Writes can be done locally first and then replicated asynchronously to others.

Eventual Consistency

If no new writes occur, all replicas will eventually converge on the same value.

Used in high-availability systems like DynamoDB and Cassandra.

You trade immediate correctness for higher availability and better partition tolerance.

CAP Theorem

These consistency choices connect directly to the CAP theorem, which says a distributed system can only provide two out of three at the same time:

Consistency (C): Every read returns the latest write (or an error).

Availability (A): Every request gets a response (even if it’s outdated).

Partition Tolerance (P): The system keeps working even if the network breaks into parts.

So why not all three?

Network partitions (P) are common in distributed systems. When they occur, the system must choose between:

Consistency (C): Stop serving outdated data until the partition heals.

Availability (A): Serve whatever data is available, even if outdated.

Thus, a system can be CP, AP, or CA, but never all three at the same time. (There is always a tradeoff.)

Next, we look at scalability techniques… the reason distributed systems exist in the first place: to handle more load than a single machine ever could.