Timsort Algorithm - A Deep Dive

#123: The Fastest Real-World Sorting Algorithm

This post outlines Timsort, a popular sorting algorithm known for its speed and efficiency.

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Timsort is one of those foundational sorting algorithms used everywhere, but most explanations of how it works shy away from going into its behavior in depth.

We are going to fix that in this newsletter.

By the end, not only will you be able to explain how Timsort works at various levels of detail, but you will also see a simplified JavaScript implementation so you can see how the concepts translate into an implementation you can try out on your own computer.

Let’s dive in!

Find out why 150K+ engineers read The Code twice a week (Partner)

Tech moves fast, but you’re still playing catch-up?

That’s exactly why 150K+ engineers working at Google, Meta, and Apple read The Code twice a week.

Here’s what you get:

Curated tech news that shapes your career - Filtered from thousands of sources so you know what’s coming 6 months early.

Practical resources you can use immediately - Real tutorials and tools that solve actual engineering problems.

Research papers and insights decoded - We break down complex tech so you understand what matters.

All delivered twice a week in just 2 short emails.

Sign up and get access to the Ultimate Claude code guide to ship 5X faster.

(Thanks for partnering on this post and sharing the ultimate claude code guide.)

I want to introduce Kirupa Chinnathambi, a connoisseur of explaining hard technical topics in a simple, easy-to-digest way:

He has been blogging since 1998 (hello, Geocities!) and has turned this hobby into a way to help hundreds of thousands of people through numerous articles, videos, community forum posts, a popular newsletter, and best-selling books.

In parallel, he is a hands-on Product Manager at Microsoft, working at the intersection of how AI and developers can build great things faster and more securely on Windows.

Introduction

When it comes to sorting algorithms, none of them is perfect.

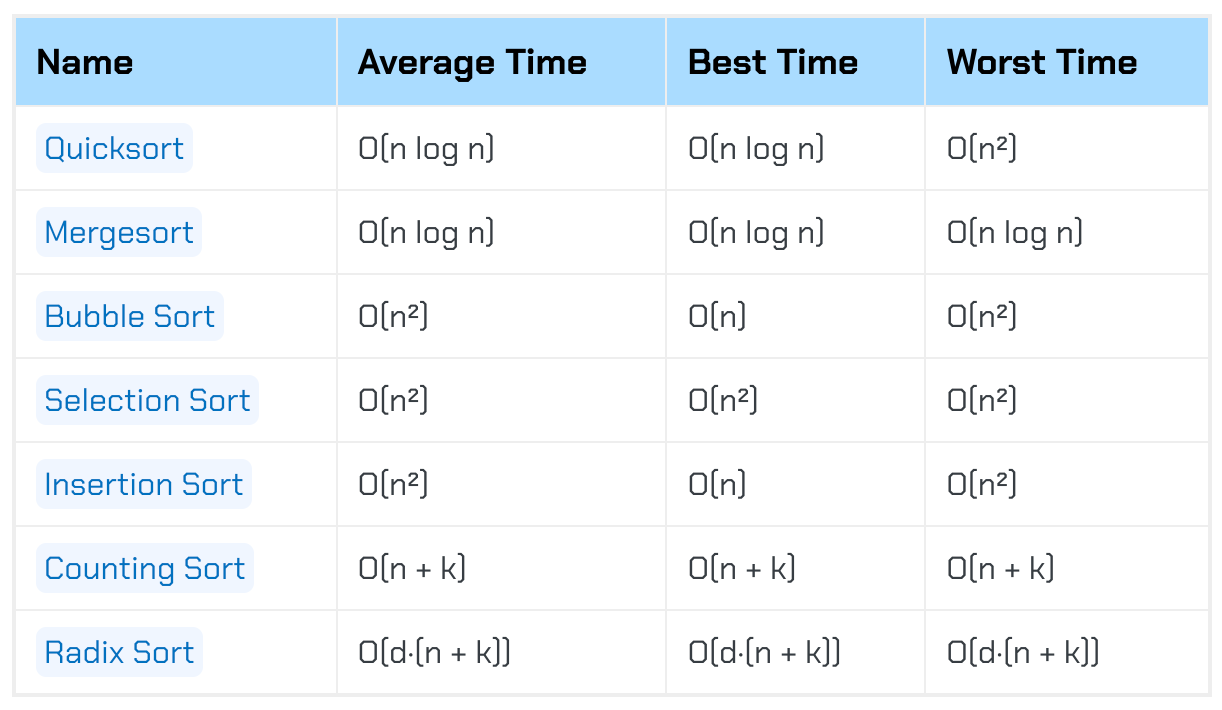

Take a look at the following table of running times for the sorting algorithms we’ve seen so far:

These sorting algorithms that seem perfect often show really poor behavior in worst-case scenarios. Their best-case performance may be suboptimal, too.

Take quicksort1, for example.

Quicksort looks pretty good, right? On average, it runs at a very respectable O(n log n) time. Now, what if we ask it to sort a fully sorted collection of values, and our pivot selection is having an off day? In this case, quicksort will slow to a crawl and sort our input with an O(n²) time.

That makes it as bad as some of our slowest sorting algorithms.

The opposite holds true as well.

Our slowest sorting algorithms, like Selection Sort, Insertion Sort, or Bubble Sort, have the potential to run really fast. For example, Bubble Sort normally runs at O(n²). If the values we ask it to sort happen to already be sorted, Bubble Sort will sort the values at a blazing fast O(n) time.

That’s even faster than Quicksort’s best sorting time:

How well our sorting algorithms work depends largely on the arrangement of our unsorted input values:

Are the input values random?

Are they already sorted?

Are they sorted in reverse?

Is the range of values inside them large or small?

Based on our answers to these questions, the performance of our sorting algorithms will vary.

As we described a few seconds ago, seemingly great sorting algorithms will crumble with the wrong arrangement of values, and terrible sorting algorithms will shine on the same arrangement of values.

So...what can we do here?

Instead of using a single sorting algorithm for our data, we can choose from a variety of sorting algorithms optimized for the kind of data we are dealing with. We can use something known as a hybrid sorting algorithm. A hybrid sorting algorithm takes advantage of the strengths of multiple sorting algorithms to create some sort of a super algorithm…like our T-Rex over here:

By relying on multiple sorting algorithms, we can minimize the worst-case behavior of individual sorting algorithms by switching between algorithms based on the characteristics of the unsorted input data being sorted.

In this newsletter, we are going to learn about one of the greatest hybrid sorting algorithms ever created. We are going to learn about Timsort.

Onward.

What is Timsort?

Timsort is a hybrid sorting algorithm that combines the best features of two other sorting algorithms:

Merge sort (where you divide your input, sort, merge recursively),

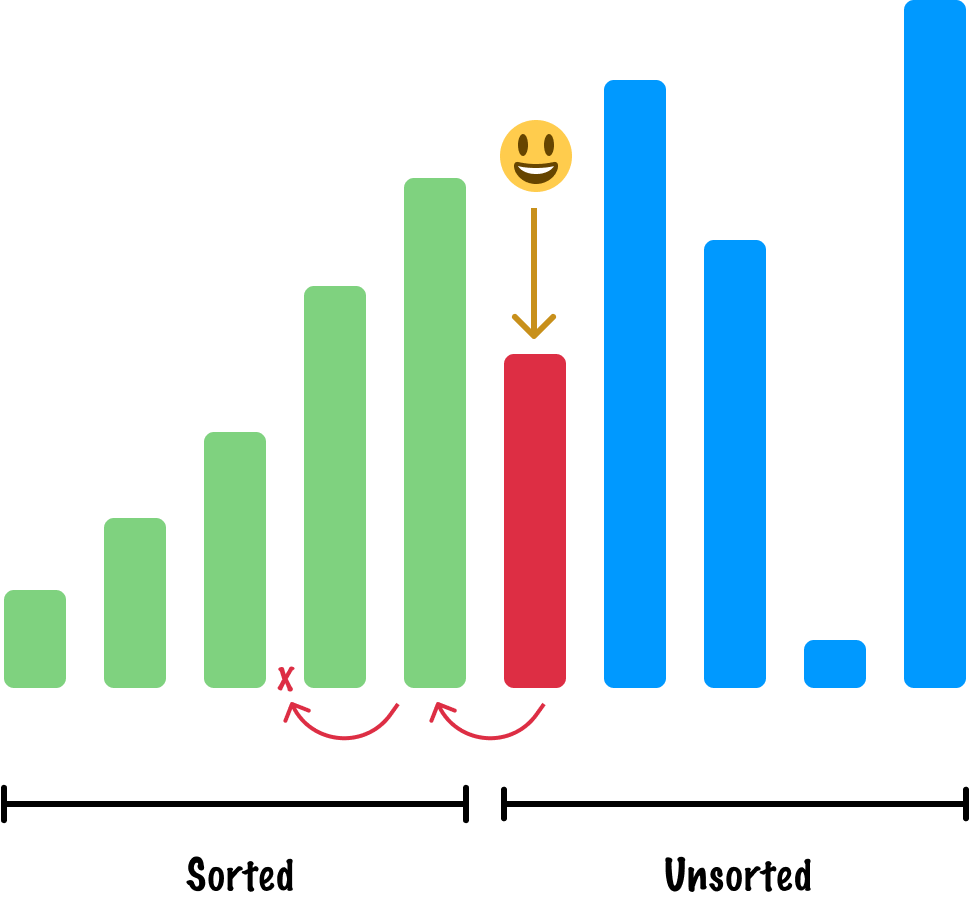

Insertion sort (where you start from a blank output and insert elements into place).

The key idea behind Timsort is to take advantage of the existing order in the data. It’s especially efficient for real-world scenarios where the values we’ll be sorting will often have some pre-existing order or patterns.

The way Timsort works can be grossly oversimplified as follows:

Divide the data into small chunks

Sort these chunks using Insertion sort

Merge the sorted chunks using a smart merging strategy found in Merge sort

The best way to make sense of how Timsort works is by walking through an example, so we’ll do that next.

Walkthrough

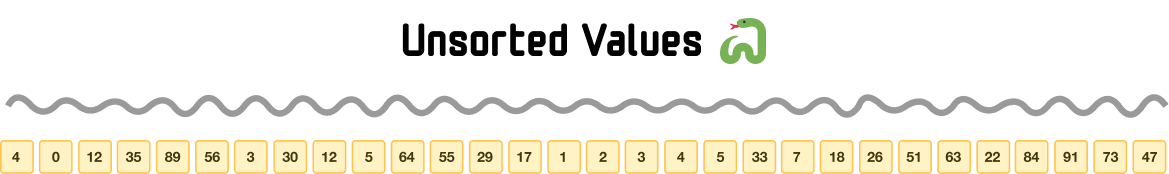

As with all great sorting algorithm walkthroughs, we’re going to start with some unsorted data that needs to be sorted:

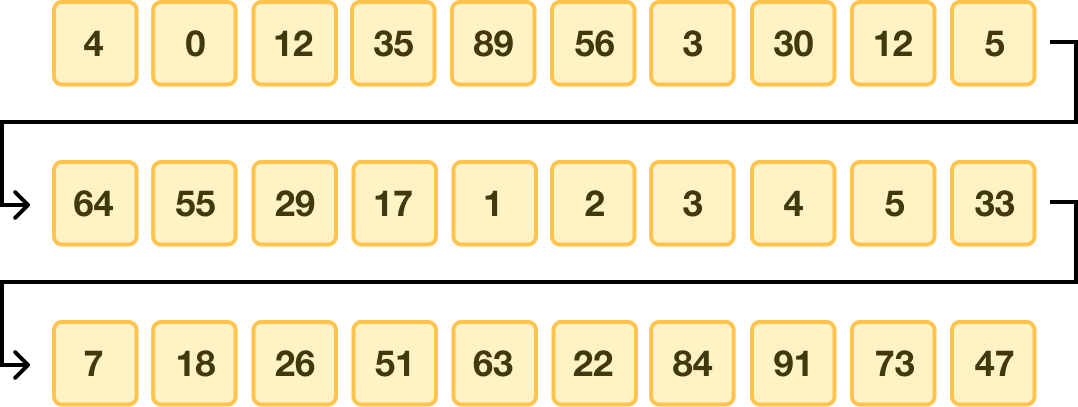

This list of unsorted values is pretty long to help us better appreciate how Timsort works. To help make all of this data easier for us to visualize here, let’s wrap this long list of data as follows:

Nothing about our data has changed except how we can represent it on this page.

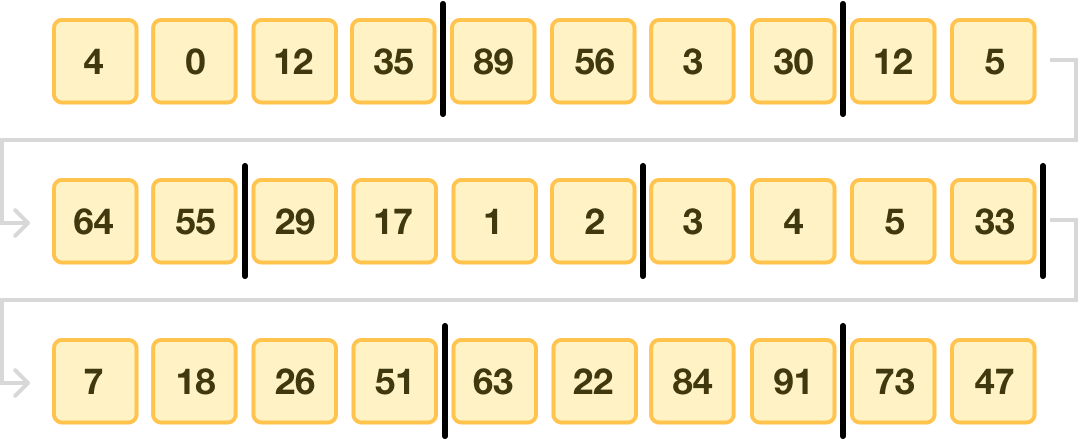

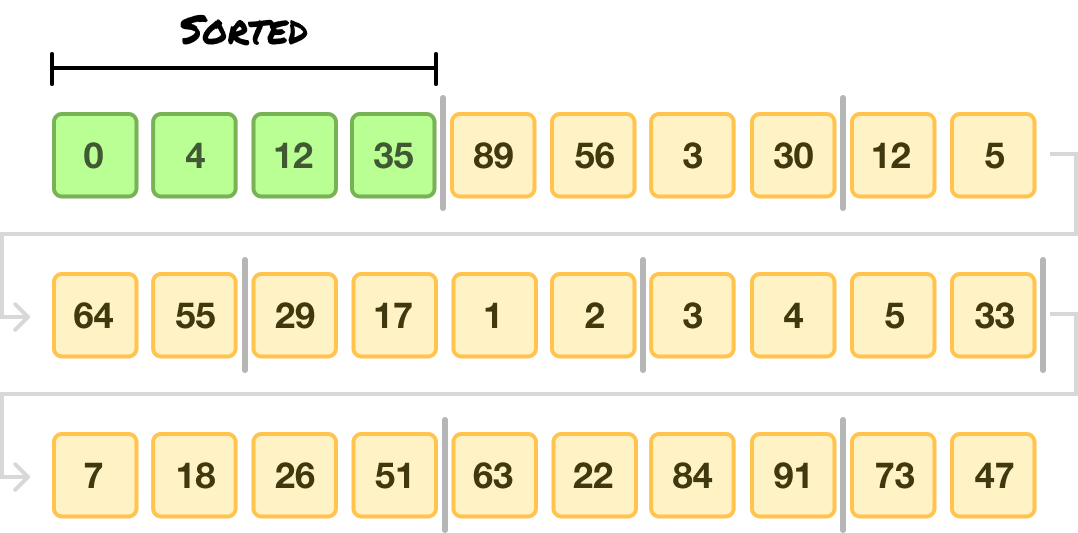

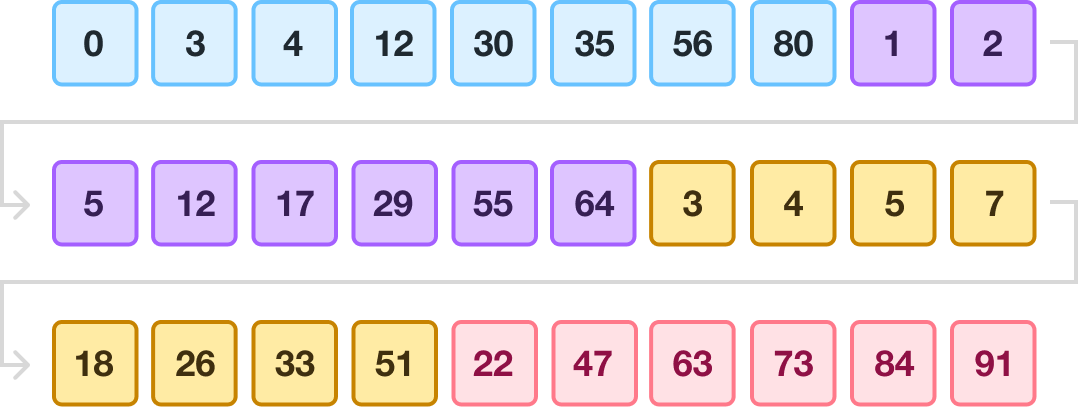

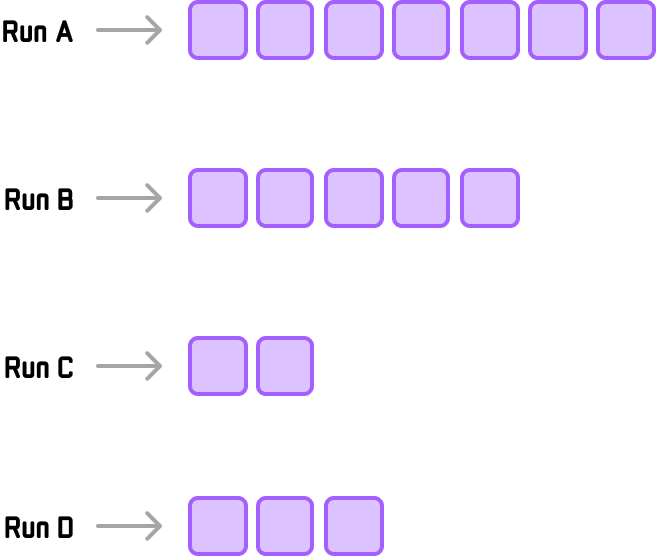

The first thing we do with Timsort is divide the data we wish to sort into smaller chunks. These chunks are more formally known as runs. The size of these runs usually varies between 32 and 64 items, but for our example, we’ll keep the size of our runs much smaller at 4:

Notice that we divided our entire unsorted collection into runs of four items each, except for the last run, which only has two values.

Sorting with Insertion Sort

Now that we have our runs, we apply insertion sort on each run to sort these values. We sort our first run:

Next, we sort our second run:

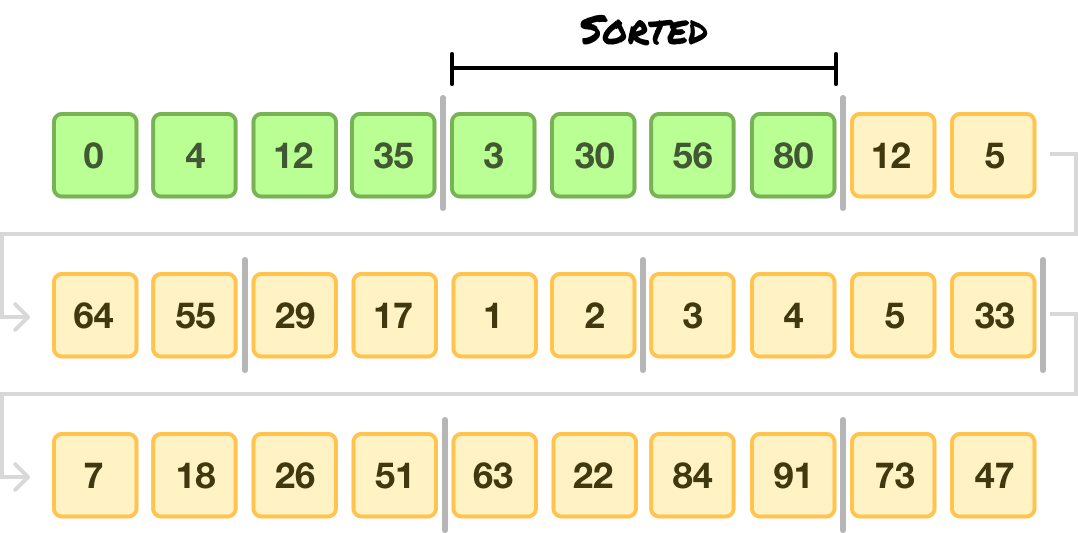

This sorting repeats until all of our individual runs are sorted:

An important detail is that only the values within each run are sorted.

In aggregate, our collection of items is still unsorted. We will address that next.

Merging Runs

The final step is to take our individually sorted runs and merge them into larger and larger sorted runs. At the end of all this, the result will be one combined sorted collection of data.

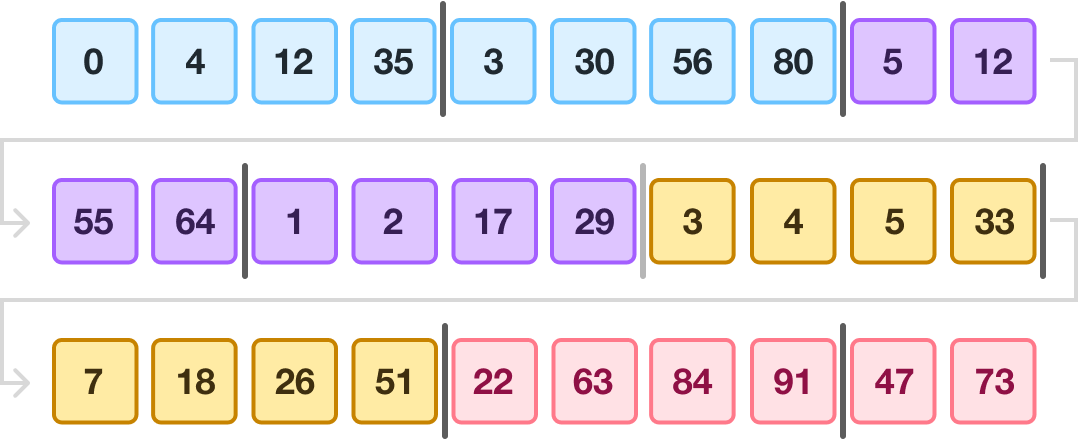

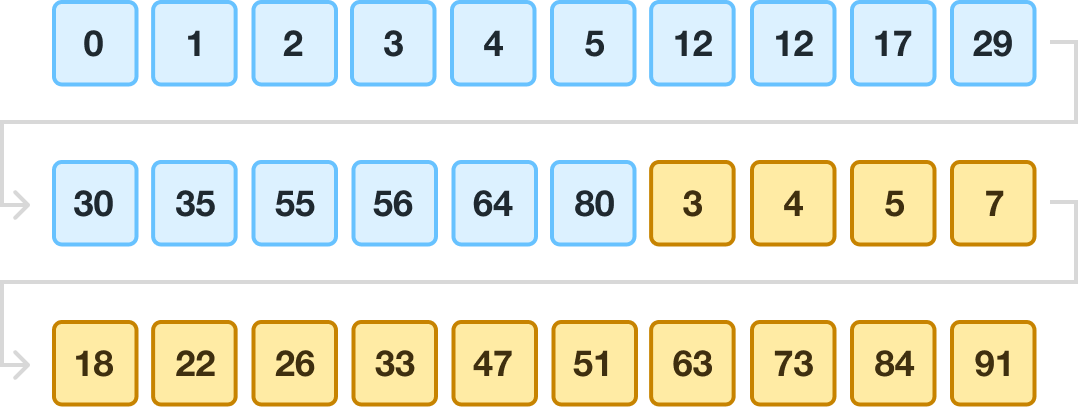

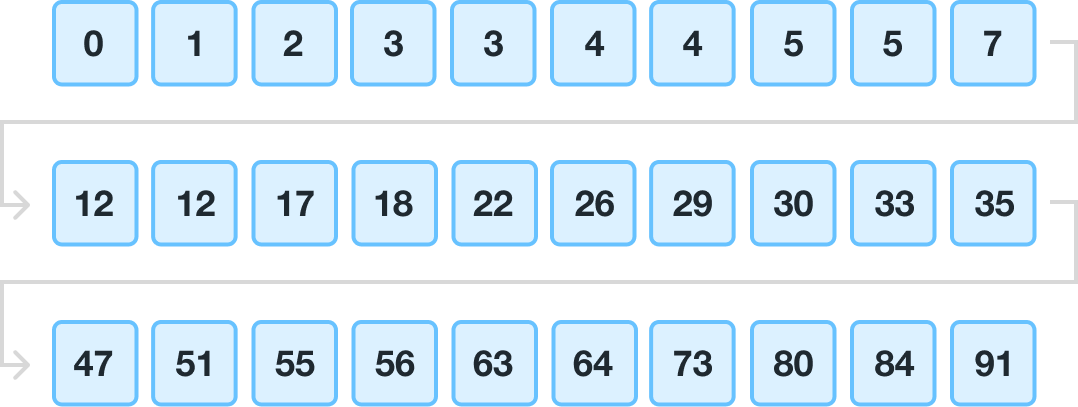

We start by merging adjacent runs together, and I have color-coded the adjacent runs that will be merged first:

The merging operation will use a subset of merge sort’s capabilities, where we need to merge the individually sorted runs into a final sorted order.

After the first round of merging, our collection will look as follows:

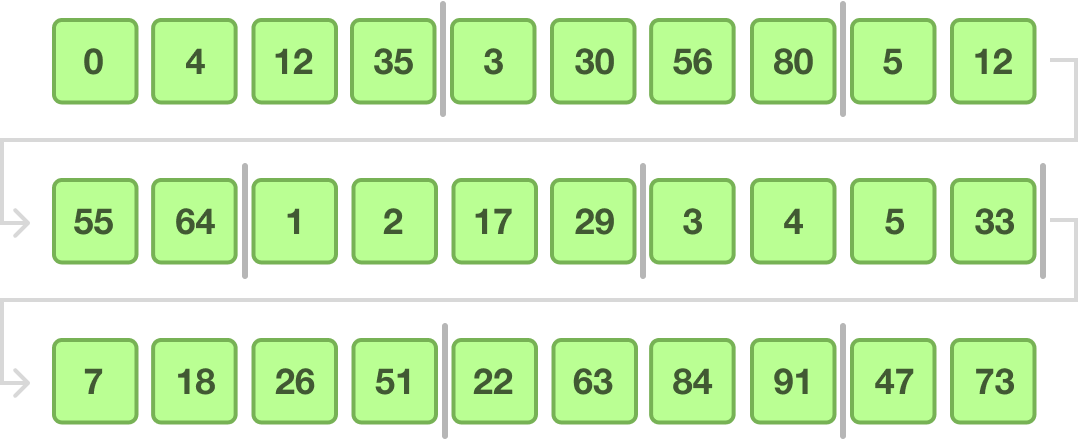

Our runs are now around double in size. We now repeat the process by merging adjacent runs again. After this round of merging, we will be left with two sorted runs:

We are almost done here. All that remains is one last step, where we merge our two unsorted runs to create our sorted output:

At this moment, no further runs need to be merged.

Timsort is finished sorting our data. Also, at this very moment, you probably have many questions about what exactly happened to make Timsort seem like a superior sorting algorithm to most other sorting algorithms out there.

We’ll address that next.

Optimizations

The above walkthrough highlighted how we can use Timsort to sort our unsorted collection of numbers.

We broke our larger input into runs, sorted each run using insertion sort, and then merged adjacent runs until we had a single fully sorted run.

If we analyzed our walkthrough at face value, Timsort’s performance may not seem very fast when we have n items, n2 running time for insertion sort, and a logarithmic running time for merging values. This is where some optimizations Timsort is known for kick in…dramatically speeding things up in many cases.

These optimizations focus on detecting common patterns in our data and customizing next steps based on how the data is structured.

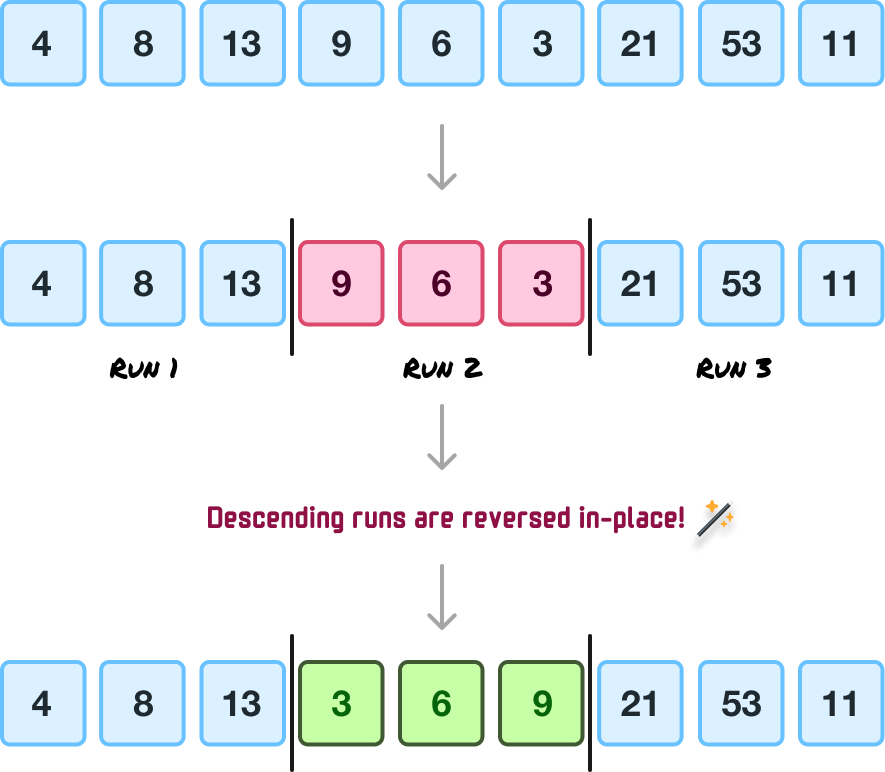

Detecting Ascending and Descending Runs

The worst-case running time for insertion sort occurs when the values to be sorted are in reverse order.

To avoid this, Timsort will try to identify runs that are strictly in reverse (aka descending) order and do an in-place reverse on them first before attempting to sort and merge them:

The best-case performance of insertion sort occurs when the runs are in ascending order.

In these cases, the runs are left as-is. There is no need to sort them. The only real work Timsort will need to perform is merging, which is consistently fast.

Galloping Mode and Already Sorted Runs

Galloping mode (also known as binary search insertion by distant friends and relatives) is an optimization technique used in Timsort algorithm during the merging phase. It’s designed to handle cases where a run has many elements that are already in their final sorted position relative to the other run.

Here’s how it works:

During merging, if Timsort notices that many consecutive elements from one run are being chosen, it switches to galloping mode.

In galloping mode, instead of comparing elements one by one, Timsort jumps (or “gallops”) over multiple elements at a time, making the merging faster

This can significantly reduce the number of comparisons needed when merging runs that are already partially ordered relative to each other.

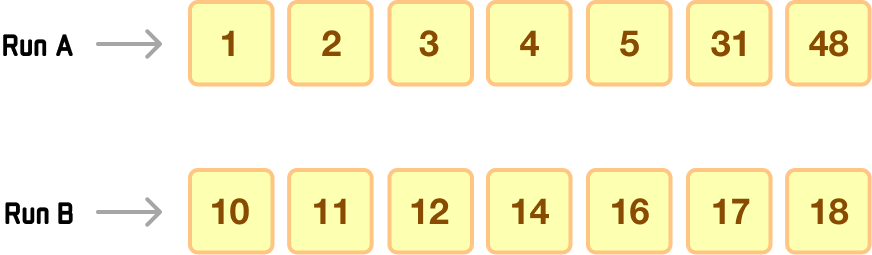

This will make more sense with an example, so here are two sorted runs we would like to merge:

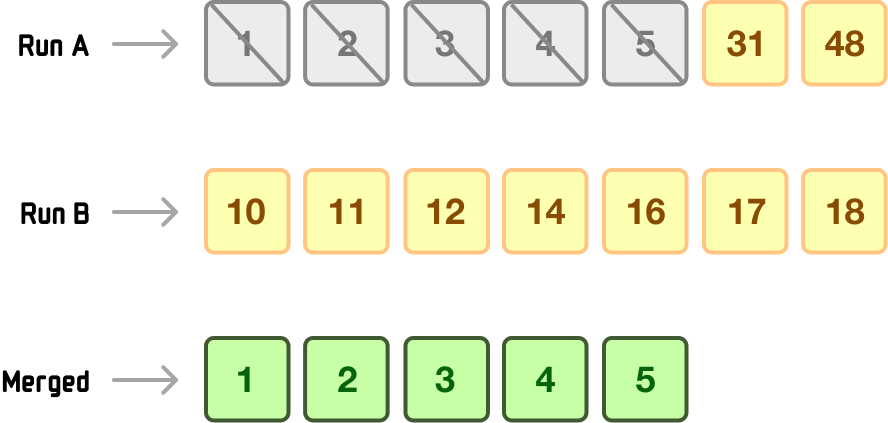

In an unoptimized merge, we would compare each element between both runs and add the smaller of the values to our merged collection.

When we look at the values in Run A, we can see that the first five numbers are all consistently less than the first value in Run B. If we elaborate on that using a loose array-like syntax, we have:

Compare RunA[0] (1) with RunB[0] (10): 1 is smaller, so 1 is added to the merged collection.

Compare RunA[1] (2) with RunB[0] (10): 2 is smaller, so 2 is added to the merged collection.

Compare RunA[2] (3) with RunB[0] (10): 3 is smaller, so 3 is added to the merged collection.

Compare RunA[3] (4) with RunB[0] (10): 4 is smaller, so 4 is added to the merged collection.

Compare RunA[4] (5) with RunB[0] (10): 5 is smaller, so 5 is added to the merged collection.

At this point, our merged collection looks as follows:

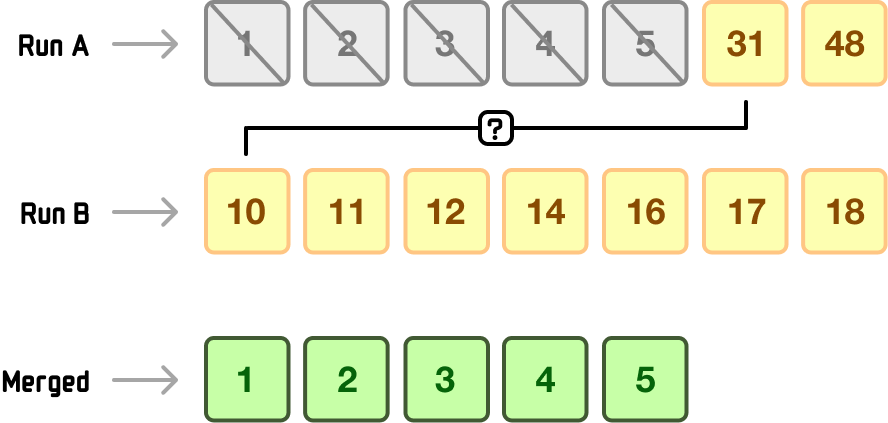

Now, Timsort will compare RunA[5] (31) with RunB[0] (10):

At this point, 10 is smaller than 31, so Timsort will now check the next few elements from Run B to see if they should be added in bulk:

Compare RunA[5] (31) with RunB[1] (11): 11 is smaller, so Timsort continues.

Compare RunA[5] (20) with RunB[2] (12): 12 is smaller, so Timsort continues.

Compare RunA[5] (20) with RunB[3] (14): 14 is smaller, so Timsort continues.

Compare RunA[5] (20) with RunB[4] (16): 16 is smaller, so Timsort continues.

Compare RunA[5] (20) with RunB[5] (17): 17 is smaller, so Timsort continues.

Compare RunA[5] (20) with RunB[6] (18): 18 is smaller, so Timsort continues.

Since all elements in Run B are smaller than RunA[5], Timsort adds them all at once to the merged collection:

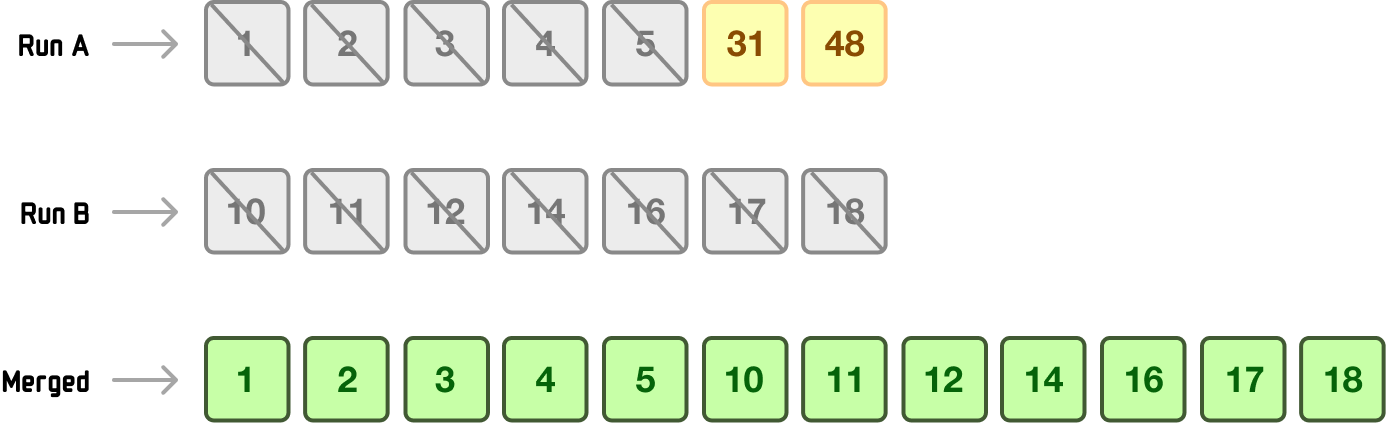

After adding all the elements from Run B, Timsort reverts to the regular comparison mode and continues merging the remaining items. In this case, both 31 and 48 from Run A will be added to the end of the merged collection.

By using galloping mode, Timsort can speed up merging by quickly adding multiple consecutive elements from one run when it’s clear they are all smaller (or larger) than the next element in the other run.

This reduces the number of comparisons and overall sorting time, especially when merging runs of significantly different sizes.

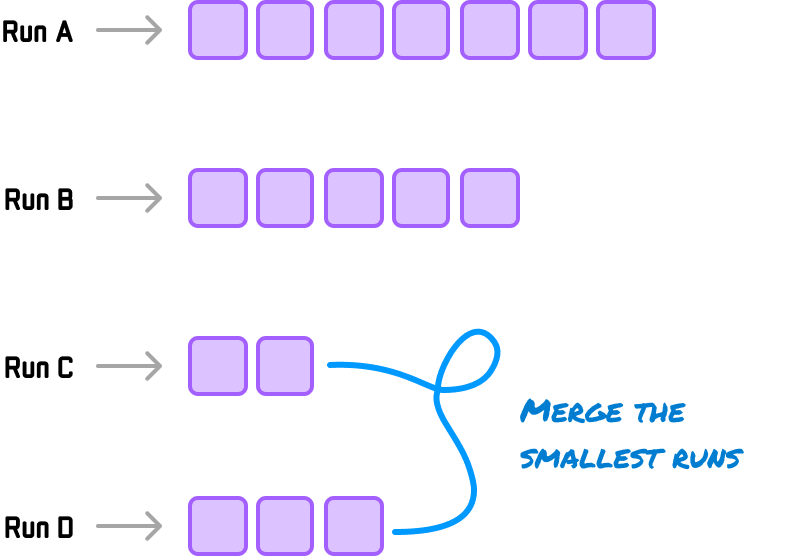

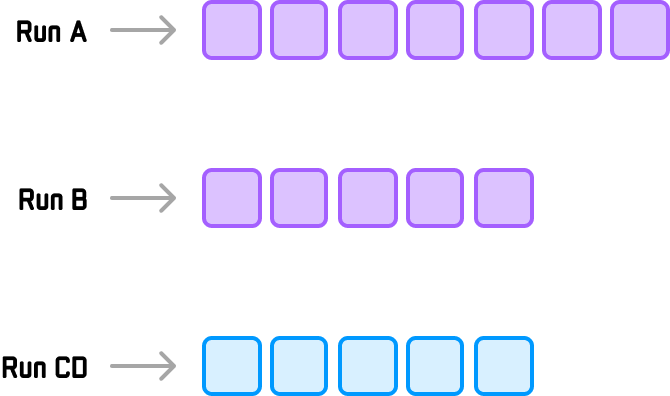

Adaptive Merging

Timsort’s merging strategy is adaptive, meaning it can vary the merging order based on the sizes of the runs. The goal is to maintain balance among the runs and avoid having a single, large run at the end that would make the final merge costly.

For example, let’s say these are the runs we are dealing with:

The actual values of the runs aren’t important.

What is important is the size of the runs. To avoid any run from being too large and making the merge waaaaay unbalanced, we start by merging the two smallest runs:

This would result in Runs C and D merging to create Run CD:

This process continues to ensure that the smallest runs are merged into a final merge pair with similar sizes.

Insertion Sort All the Way for Smaller Inputs

Yes, insertion sort is a slow sorting algorithm.

When sorting a small number of values, though, this slowness isn’t very noticeable. This is especially true in a world where our computers can process millions and billions (and trillions?) of operations a second.

For this reason, Timsort will often fall back to using plain old insertion sort when the size of the input it is trying to sort is less than the run size threshold, which is usually 32 or 64 items in length:

This avoids the added overhead of the merging operation, breaking runs, and so on.

Tying it All Together

Why is Timsort so efficient?

It’s because it tries to detect patterns in the sorted data and special-case the sorting behavior accordingly. Whether by identifying natural runs, detecting reversed runs, using galloping mode to avoid unnecessary merging-related work, enforcing minimum run lengths, or performing adaptive merges, Timsort seeks the most efficient path whenever possible.

A subtle but important detail is that these pattern matching optimizations ensure that Timsort performs well on partially sorted data, which is the most common type we will encounter in the real world.

Performance Characteristics

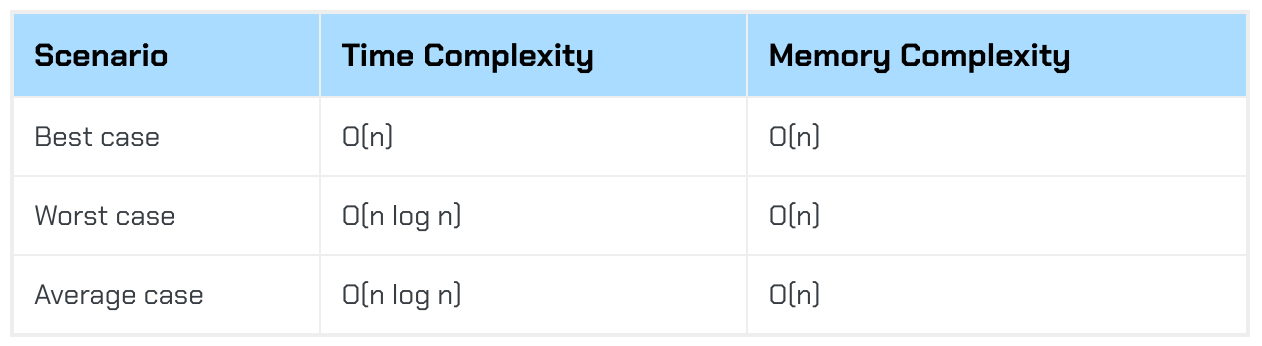

Timsort is one of the best sorting algorithms out there, and we can see it live up to its grandness when we summarize its time and memory complexity below:

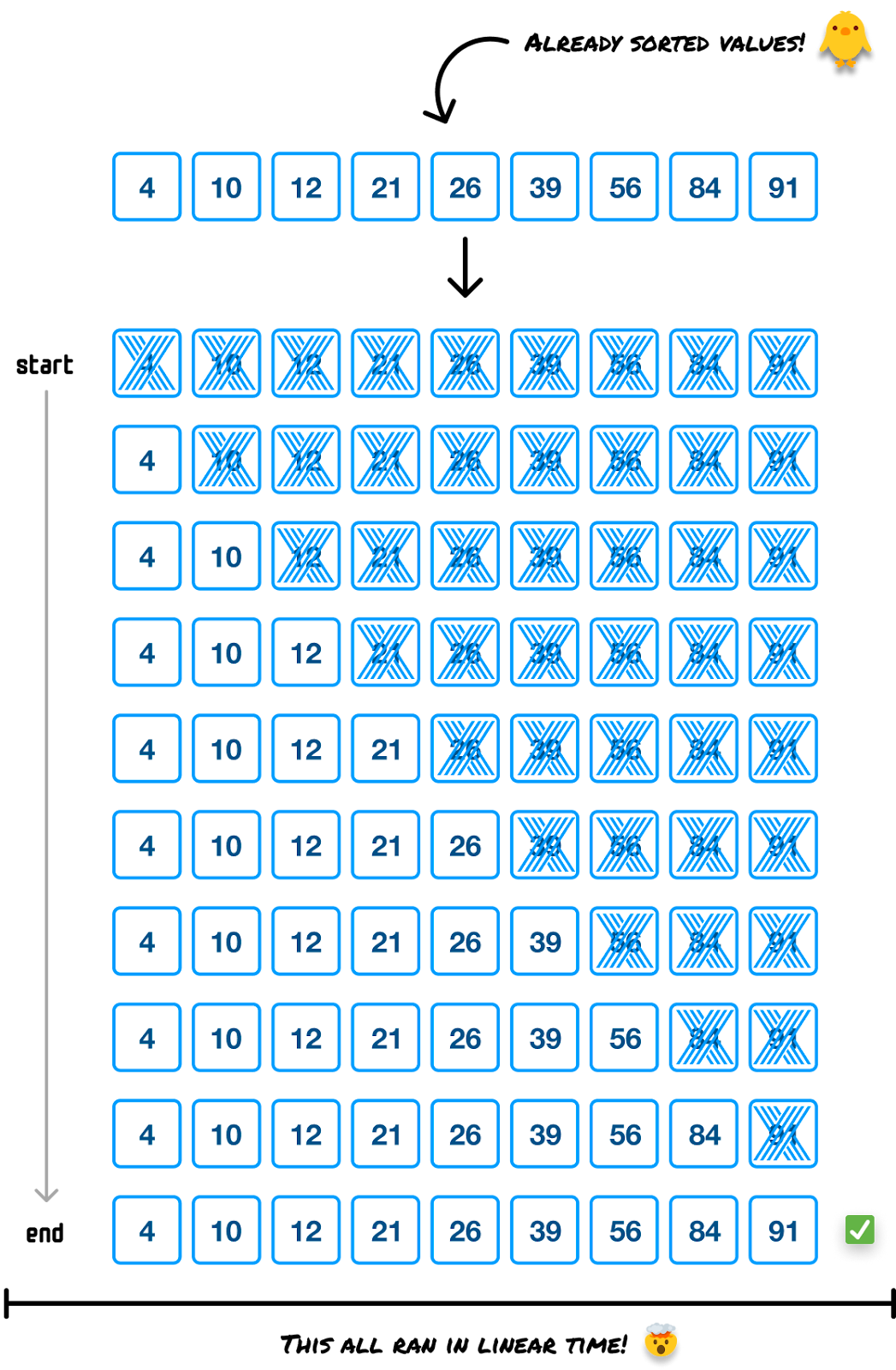

At its best, Timsort can run in linear time.

This happens when the data is already sorted or nearly sorted as part of a few large runs, and we know that Insertion Sort runs in linear time for sorted data:

Merging runs is a fast operation as well, and if we throw in any optimizations, such as galloping mode if the range of sorted numbers doesn’t overlap, the merging is almost a trivial operation.

In the average and worst cases, Timsort runs at O(n log n).

The bulk of the complexity here goes into identifying runs and merging them. This puts its performance on par with Quicksort’s average performance, but Timsort’s optimizations give it an edge as being a faster O(n log n)!

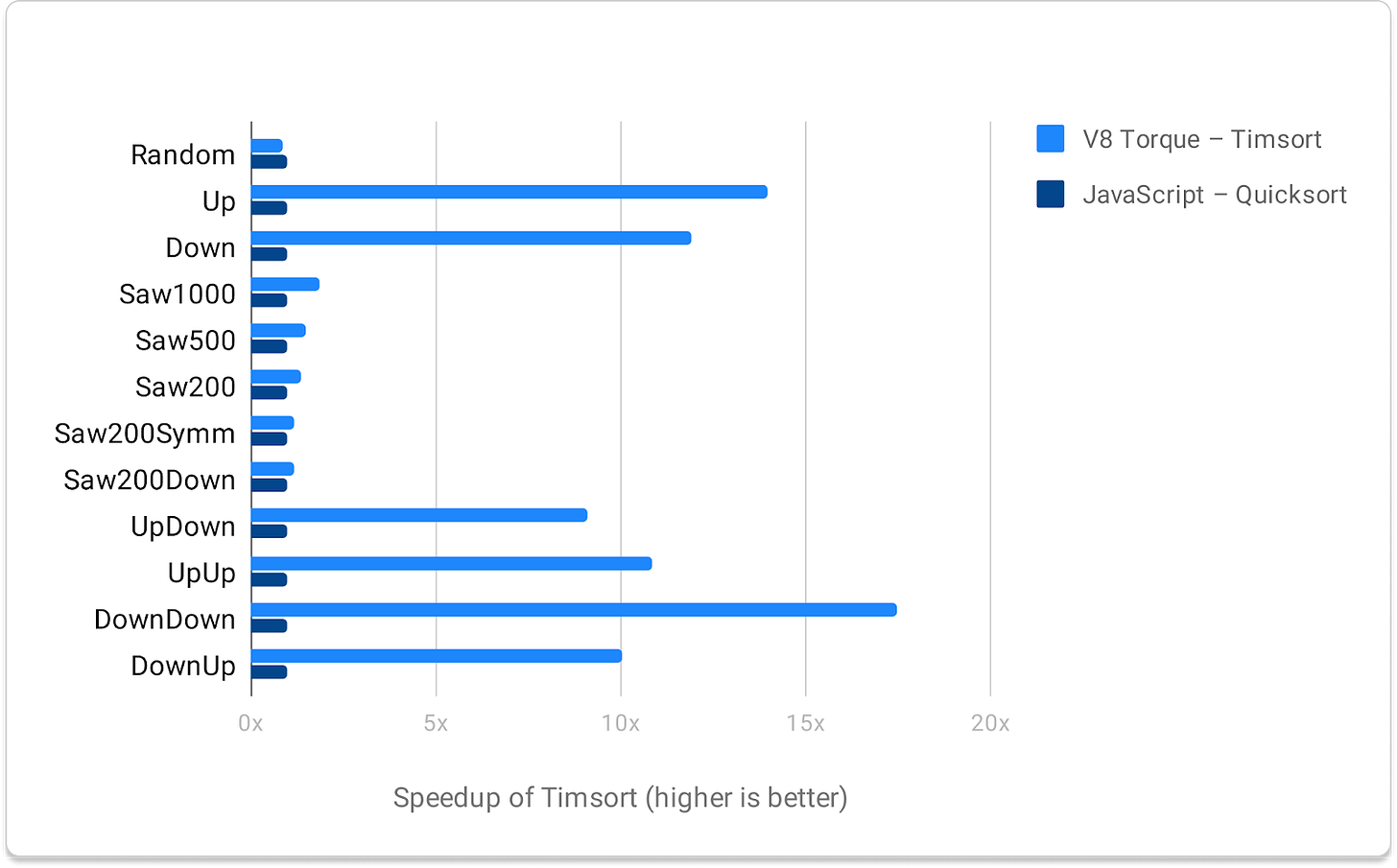

This is validated by benchmarks such as the following that compares Timsort with Quicksort on partially sorted data:

Notice how much faster Timsort is compared to Quicksort.

The more Timsort is used in real-world data scenarios, the more we’ll see it soaring faster than every other sorting algorithm we have seen so far.

Lastly, from a space point of view, Timsort needs an O(n) amount of memory to run. This has to do with the data structures Timsort creates behind the scenes when merging the runs.

The Code

Timsort is a very complex sorting algorithm to implement.

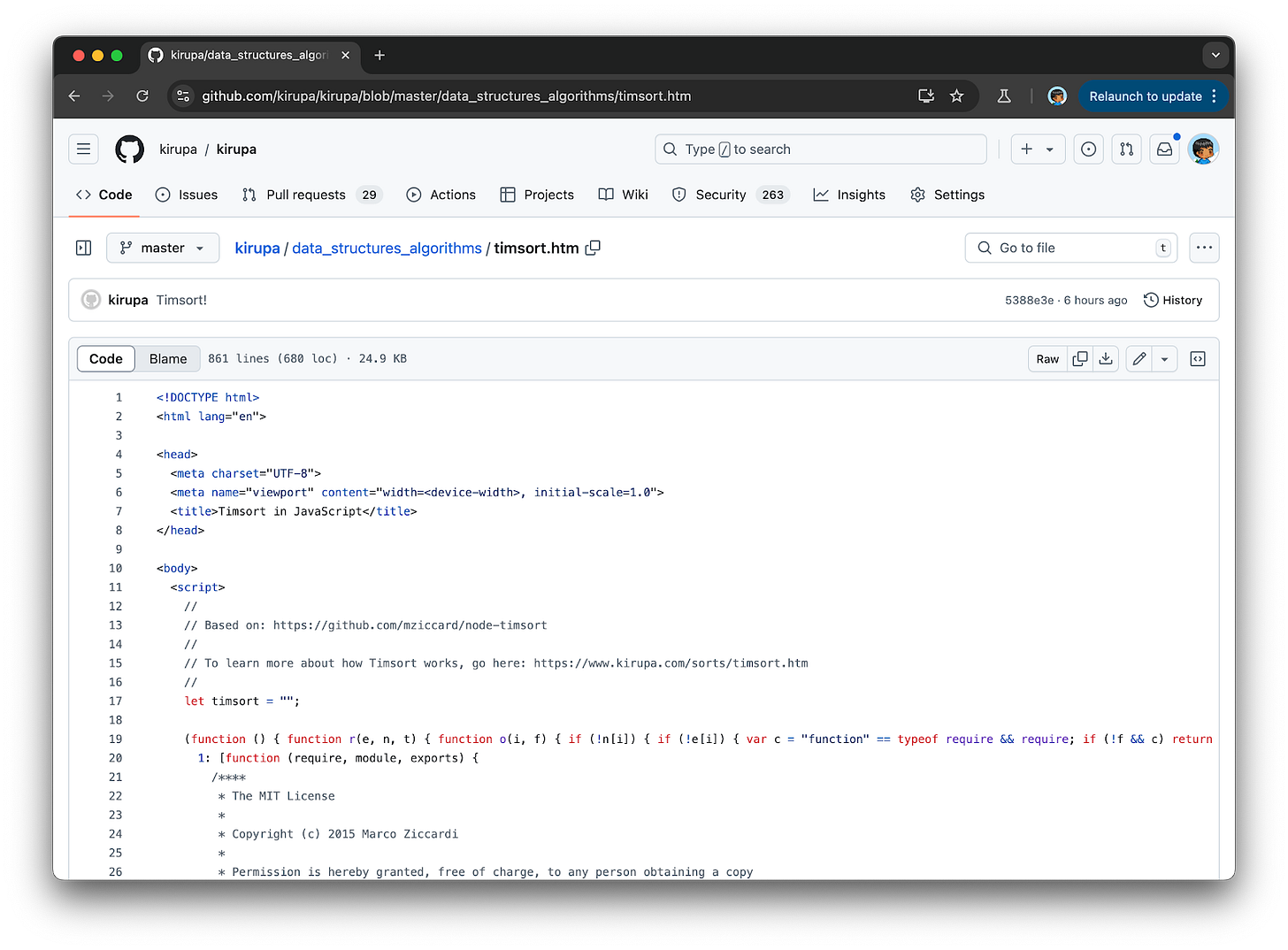

The core insertion sort and merging capabilities are straightforward. Identifying and handling all the various patterns to optimize for...is less straightforward. For that reason, most examples of Timsort we will run into are based on the original Python implementation itself. I am not going to paste the massive amount of code needed to implement Timsort in JavaScript.

Instead, here is a link to the GitHub repo where I took Marco Ziccardi’s Node.js implementation of Timsort and turned it into something that works in the browser:

As we scan through the code, we’ll see a lot of familiar patterns. Towards the bottom, the example code to initialize Timsort and use it to sort some values is provided:

let example = [-7, 10, 50, 3, 940, 1, 4, -8, 24, 40, 33, 12, 10];

// Comparison function

function numberCompare(a, b) {

return a - b;

}

// Sort our example array

timsort.sort(example, numberCompare);

console.log(example);Feel free to try it out and use this in your own projects, but as we will discuss in a few moments, Timsort is already the default sorting algorithm used in many situations in our favorite programming languages.

Conclusion

Timsort, as the preeminent hybrid sorting algorithm, is among the fastest sorting algorithms available.

When we say this, this fastest isn’t qualified with caveats where the unsorted input needs to be of a certain arrangement. Timsort’s worst-case behavior is very good. Timsort’s best-case behavior is very, VERY good. The upper and lower bounds of its performance make it an excellent choice for any kind of unsorted (or sorted) input we throw at it. This flexibility and power are what make Timsort one of the default sorting algorithms in programming languages such as Python, Java, Rust, and more.

Now, Timsort isn’t the only hybrid sorting algorithm in town.

Another popular hybrid sorting algorithm is introsort (sometimes referred to as introspective sort), which uses a combination of quicksort, heapsort, and insertion sort for its sorting shenanigans. Introsort is the default sorting algorithm in Swift, C#, and other languages. As we look ahead into the future and run into more interesting and new data scenarios, we may see more hybrid sorting algorithms emerge.

We are in the early days, so there will be more fun times ahead with hybrid sorting algorithms.

👋 I’d like to thank Kirupa for sharing this deep dive into Timsort.

For more explanations of popular data structures and algorithms, his Absolute Beginner’s Guide to Algorithms book is just what you (or a friend) will need.

You can catch all of his online content at KIRUPA.com and his newsletter.

I launched Design, Build, Scale (newsletter series exclusive to PAID subscribers).

When you upgrade, you’ll get:

High-level architecture of real-world systems.

Deep dive into how popular real-world systems actually work.

How real-world systems handle scale, reliability, and performance.

10x the results you currently get with 1/10th of your time, energy, and effort.

👉 CLICK HERE TO ACCESS DESIGN, BUILD, SCALE!

If you find this newsletter valuable, share it with a friend, and subscribe if you haven’t already. There are group discounts, gift options, and referral rewards available.

Want to reach 200K+ tech professionals at scale? 📰

If your company wants to reach 200K+ tech professionals, advertise with me.

Thank you for supporting this newsletter.

You are now 200,001+ readers strong, very close to 201k. Let’s try to get 201k readers by 25 February. Consider sharing this post with your friends and get rewards.

Y’all are the best.

If you aren’t familiar with quicksort, glance through this deep dive.