What a Supermarket Checkout Line Can Teach You About Message Queues

#118: What Is a Message Queue?

Share this post & I'll send you some rewards for the referrals.

Block diagrams created using Eraser.

Picture your last grocery trip: you filled your cart & headed to checkout.

Then the big moment arrived—you had to choose a line…Maybe you compared the number of items in other carts. Or you might have observed how quickly each cashier worked. Either way, you were making queue choices.

These are the same choices found in software systems.

In today’s newsletter, I’ll teach you how message queues work by comparing them to waiting in grocery store queues. The read time is roughly the time most people spend in line.

By the end, you’ll understand:

How message queues work

How queue behavior affects performance

How to apply these ideas to build better systems

Onward.

AI code review that knows when to stay quiet (Partner)

Unblocked is the AI code review that surfaces real issues and meaningful feedback instead of flooding your PRs with stylistic nitpicks and low-value comments.

Checkout Line = Queue

The checkout lines are simple:

Customers come with their carts and wait. Eventually, they form a line. The first person in the line gets served first. The last one needs to wait for everyone in front of them. This is called FIFO (First-In-First-Out) ordering.

It’s simple, fair, and predictable.

Software message queues work in the same way.

Requests arrive & wait in order. Think of an app like Instagram. When many users upload photos simultaneously, the app can’t process them all at once. So each photo upload becomes a message that will be processed later.

There’s a hidden insight here: queues exist to absorb bursts in demand.

Use a queue when you can’t handle every request right now but still need to handle them later.

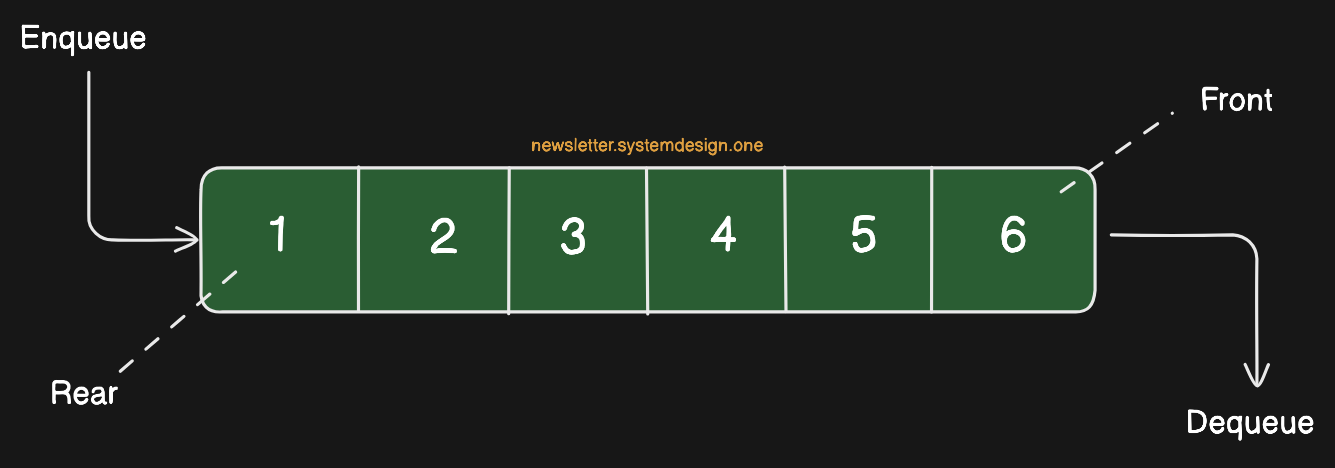

Queue mechanics are simple…

New messages get placed at the back of the queue - this is called enqueueing.

Processed ones leave from the front of the queue - this is called dequeuing.

This pattern of filling and emptying the queue is what makes it fair and predictable. Just like the supermarket checkout line.

Takeaway: Use queues to absorb sudden traffic spikes and keep track of what to process later.

Cashiers = Servers

In a supermarket, cashiers are responsible for handling customers…

Each cashier scans items, processes payments, and completes transactions. They work alone but share the same goal: move customers through checkout.

In software systems, servers work the same way…

They pull messages from queues and process them in turn. A queue growing faster than it’s getting processed is a signal to scale servers.

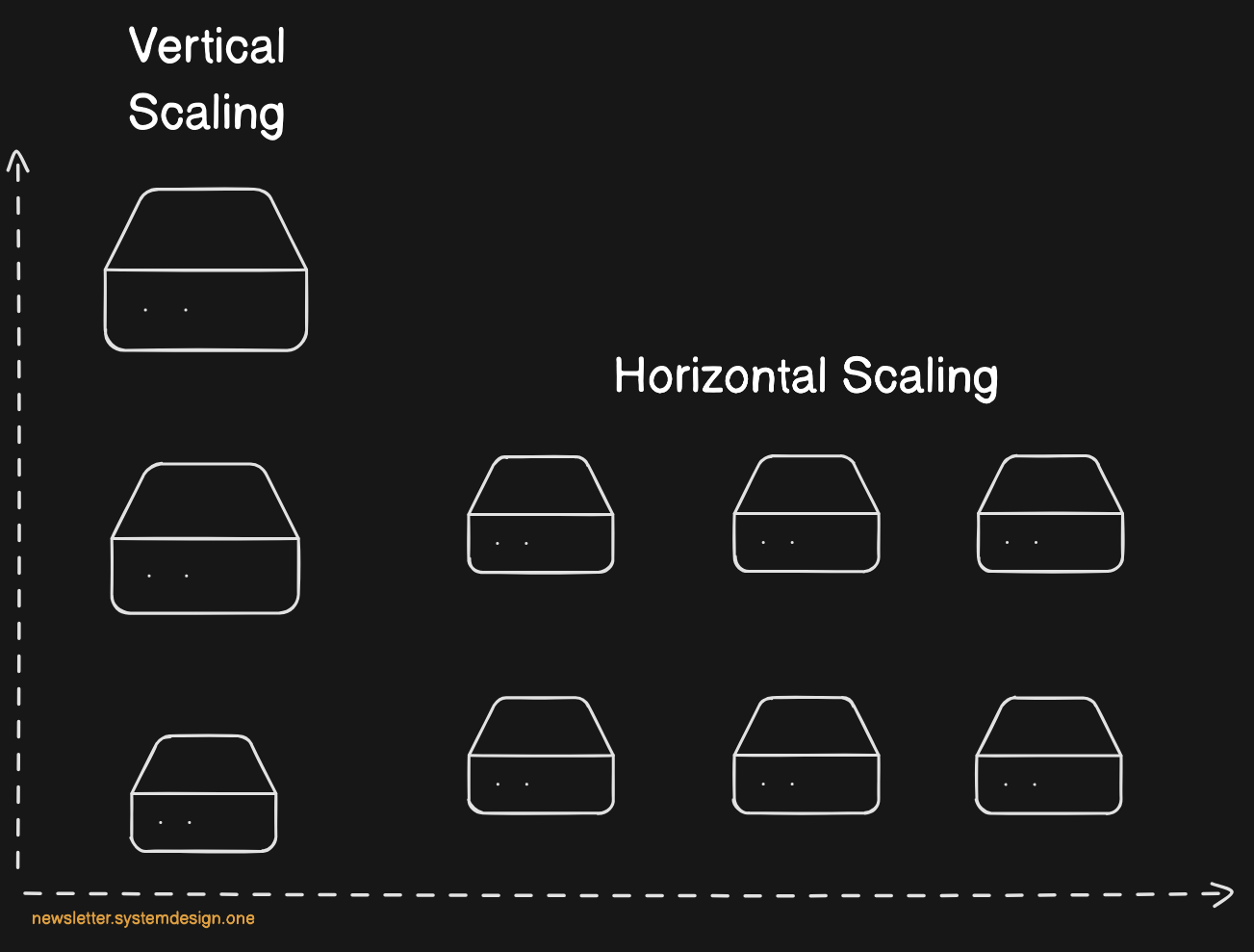

You can scale in two ways:

Horizontal scaling

This means adding more servers, so the work gets spread across workers

It’s like adding a new cashier in a supermarket; customers notice a new line opened and spread out

Vertical scaling

This means making the existing servers more powerful1

It’s like training cashiers in a supermarket; trained cashiers scan the items or process payments faster and serve more customers faster

But there’s a catch: servers must confirm they finished processing.

At the supermarket, this is like a cashier calling “Next!” when ready. This is called an acknowledgment2 in software systems. Without it, the system can’t tell if a message succeeded or failed, so it has to be redelivered.

Takeaway: Match your processing power to demand by scaling out or scaling up servers.

Let’s keep going!

Line Length, Throughput, and Latency

Longer lines mean longer waits…

Too many customers during rush hour makes waits much longer,,, and customers get frustrated. They might leave their carts or choose a different store next time.

Long queues also hurt performance in software systems:

Too many requests slow things down. Think of Twitter during big events when millions of tweets flood in. Servers can’t keep up, so users experience slow responses or errors. This is very bad for the business.

So how do you make sure you see issues before they happen?

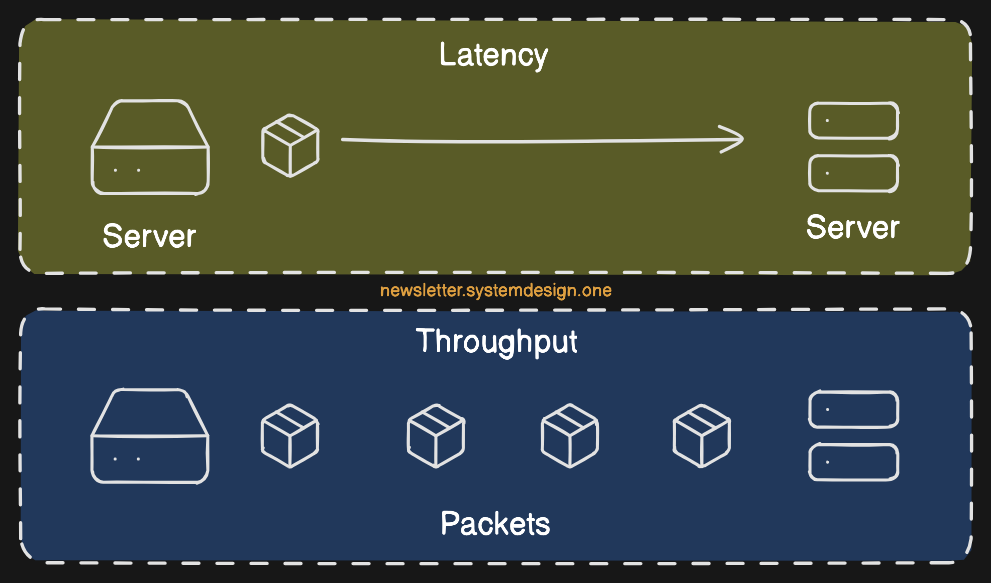

“One approach is to use throughput and latency metrics.”

Throughput3 means how many customers get handled per hour. Latency4 means how long it takes to process one customer.

A good system has high throughput & low latency.

Store managers watch checkout lines to decide whether to open more lines.

Likewise, the engineers monitor queue length, throughput, and latency to make scaling decisions. It’s required to understand acceptable limits and scale before the system crashes.

Low throughput

What it means: system can’t handle enough requests at once

Why it happens: there aren’t enough servers, or the work isn’t shared evenly

How to fix it: add more servers or spread the work

High latency

What it means: requests take too long to finish

Why it happens: when code is slow, databases are lagging, or the network is busy

How to fix it: make the code faster, use caching, or improve the slow parts

Takeaway: If queues keep growing, it means demand exceeds capacity. Use throughput and latency metrics to identify what to improve.

Ready for the next technique?

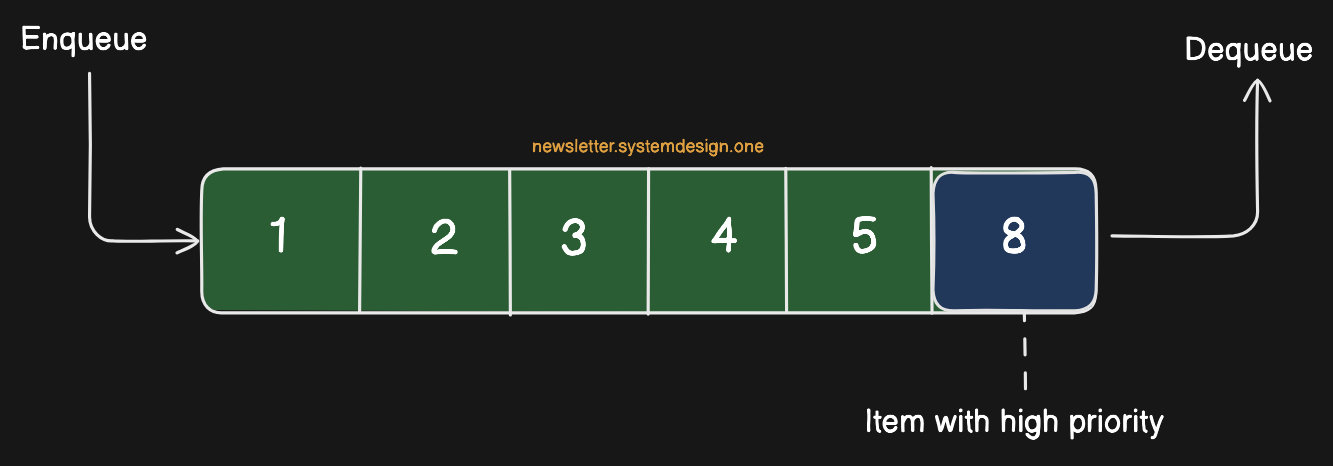

Express Lines = Priority Queues

Supermarket express lines exist to speed up checkout for customers with fewer items.

They provide a faster option for quick trips and help the store increase throughput.

This is similar to software using priority queues, where important messages are moved to the front instead of waiting in line. A priority queue assigns each message a level of importance. The system always processes the highest-priority task first, even if others arrived earlier.

Priority queues help systems improve performance, but they have downsides:

Lower-priority work can get stuck if urgent jobs never finish

Priority queues are hard to debug since there’s no FIFO ordering

Managing priorities adds complexity in implementation/maintenance

It’s a classic tradeoff between simplicity & responsiveness. It’s best to use priority queues only when speed really matters, and to keep most workflows predictable and fair.

Takeaway: Priority queues ensure time-sensitive messages aren’t delayed by less critical work.

Ready for the best part?